October 3, 2004

October 3, 2004

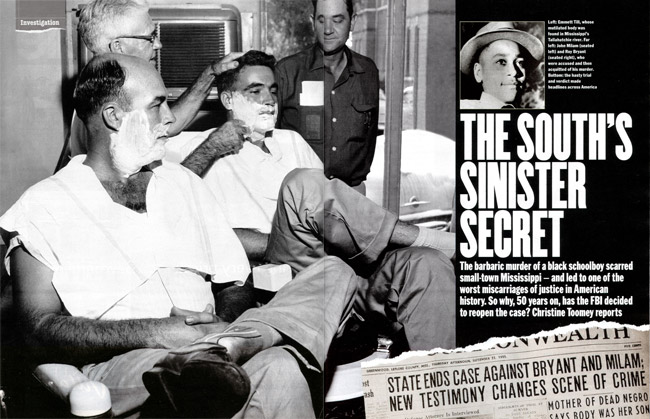

Investigation

The barbaric murder of a black schoolboy scarred small-town Mississippi — and led to one of the worst miscarriages of justice in American history. So why, 50 years on, has the FBI decided to reopen the case? Christine Toomey reports

As temperatures reached 118F in the Tallahatchie County courthouse on the afternoon of September 19, 1955, the two small ceiling fans did little to stir the stifling, soupy heat. It was the busiest time of year in the Mississippi delta — the peak of the cotton harvest — and fields stretching almost to the courthouse steps were blanketed with what locals still call “white gold”. Yet the small brick building was so packed with white farmers and their families that extra seats had to be crammed into the aisles.

The few black spectators who dared to attend were forced to the back of the room by the county sheriff, Clarence Strider, who called for cane-bottomed rocking chairs to be brought in for the comfort of the two white defendants in the trial getting under way, one of whom then sat ostentatiously twirling a cigar as he rocked himself back and forth. When the heat, humidity and fug of smoke became almost unbearable, the presiding judge invited all men in the courtroom to remove their jackets. Eventually, fearing the overcrowding was hazardous, the judge called for the courtroom to be cleared in early recess with the warning that “if fire develops anyplace in this courthouse, a great tragedy will take place”.

Though some of those present in the courthouse did not see it that way, the real tragedy had already occurred. Three weeks earlier, the horribly mutilated body of a 14-year-old black schoolboy had been discovered floating feet up in the Tallahatchie river, with a large industrial fan wrapped around his neck with barbed wire. The boy’s tongue and eyes had been gouged out, his skull crushed and his genitals mutilated before he was shot in the head.

The boy’s name was Emmett Louis “Bobo” Till, and it would be repeated by poets, songwriters and playwrights for years to come. Till was not from the Deep South. He was from Chicago, so was unschooled in what passed for “southern etiquette” — the sort that called for black males to bow their heads and step off the pavement if they saw a white woman approaching. He was spending the summer with his great-uncle and cousins on the outskirts of a down-at-heel Mississippi community inappropriately called Money.

In the mornings the boys helped out in the cotton fields. In the afternoons they were allowed to take a trip to the nearby country store — Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market — to buy sodas, sweets and bubblegum. Till had only been in Money a few days when rumours started to circulate that he had wolf-whistled at the young wife of the white storekeeper Roy Bryant, and maybe even suggested he take her on a date. Bryant was driving a shrimp truck to Texas at the time. But when he returned four days later, the boy was hauled from his bed in the middle of the night by Bryant, his cigar-chomping half-brother, John Milam — and, it was claimed, up to 10 others — stripped naked and tortured for hours before being shot. One witness, prevented from testifying to what he knew of the brutal murder, was smuggled out of the state of Mississippi in a coffin for fear that he too would be killed.

While most lynchings in the American south — and Mississippi had the worst record of all — had been hushed up or ignored to that point, the murder of Emmett Till was different. When his body was returned to his mother in the north, she insisted that his funeral casket remain open so that people could see how he had been brutalised before being killed; 50,000 people filed past the coffin, some fainting at the sight. The resulting national and international outcry made it impossible to sweep the murder under the carpet. In a hurry to calm public outrage and appear to be addressing what had happened in their midst,county officials called for a trial to be held just three weeks after Till’s murder.

But holding a trial was still a far cry from convicting those responsible. After listening to a series of testimonies identifying Bryant and Milam as having abducted Till, the all-white, all-male jury retired for 65 minutes to deliberate. Bill Minor, then a journalist for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, still remembers hearing laughter coming from inside the room where the jury sat. One juror later admitted that they would have emerged to deliver their verdict in half the time had they not stopped for a “soda break”. When the foreman of the jury returned a verdict of “not guilty” on both men, Minor recalls the courtroom erupting “like it was a Fourth of July celebration”. Both Milam and Bryant then posed for the cameras in the courtroom, bouncing their brood of young sons on their knees and kissing their wives at length. Soon afterwards, protected by the double-jeopardy law — meaning they could not be retried on charges of which they had already been found innocent — the men sold their story to the now-defunct Look magazine for $4,000. In it they admitted they had murdered Till, though their intention had been to “just whip him and scare some sense into him”. “But we were never able to scare him. He was hopeless,” said Milam. Till, he said, kept shouting: “I’m not afraid of you. I’m as good as you are.”

“So I just made up my mind,” Milam boasted. “‘Chicago boy,’ I said. ‘I’m tired of ’em sending your kind down here to stir up trouble. Goddam you. I’m going to make an example of you — so everybody can know how me and my folks stand.’ I’m no bully. I like niggers in their place. I know how to work ’em,” he bragged. “But I decided it was time a few people got put on notice.”

The appalling crime and blatant miscarriage of justice was one of the sparks that set the civil- rights movement alight in America’s Deep South. The grotesque murder, hasty trial and subsequent confession of Till’s killers was headline news in late summer and autumn 1955. Three months after the trial ended, Rosa Parks famously refused to move to the back of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama, saying later that uppermost in her mind that day was the murder of Emmett Till. Martin Luther King also cited Till’s murder as one of the most egregious injustices that fuelled his passion in opposing segregation. Now, nearly half a century after Till was killed, the FBI has announced that it will help the district attorney’s office in the state of Mississippi to reopen its investigation into the case. Bryant and Milam are now dead; Milam died of cancer in 1980 and Bryant of the same disease 10 years later. But investigators for the DA’s office and FBI agents have begun sifting through old files and interviewing witnesses, some for the first time. The expectation is that others believed to have been connected with the crime may now face criminal charges of conspiracy to murder or attempting to pervert the course of justice by covering it up.

Some are dismissing this as a cynical ploy by a Republican administration keen to garner votes at a time when George W Bush is struggling for re-election. Few black voters, overwhelmingly Democrat, are likely to be swayed; Bush’s record on furthering race relations and improving the lives of American minorities is seen by most as dismal. But the fiercest battleground for control of the White House in November’s election is being fought in the Midwest states. It is here that those who support Bush welcome any initiative that might help paint a picture of the president as a more “caring and compassionate conservative”.

Yet many are already questioning the move. What is really to be gained, they ask, from reopening such a painful chapter in the country’s recent history? The answer to this question lies among those who still live close to the small rural community of Money, in what visitors arriving at the airport in Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, are assured is America’s “New South”.

There are no road signs left to show where Money begins or ends. Since the cotton plantations in the area became mechanised, most inhabitants have moved away. The only public building left is a part-time post office in a Portakabin parked in a stand of sprawling oak and magnolia trees by the roadside. To one side of it looms a giant disused cotton gin; to the other, the ruins of what was once Bryant’s grocery, where Emmett Till went to buy bubblegum with his cousins.

Exactly what happened on the last afternoon that Till went to that store before he was killed was the subject of heated debate at the time of the trial. That he wolf-whistled as he left the store there was little dispute. But in court, Carolyn Bryant claimed Till had come into the store alone, grabbed her hand and said, “How about a date, baby?” and then blocked her as she tried to get away, saying: “You needn’t be afraid o’ me. I been with white girls before.”

Till’s cousins disputed this and said he had whistled at two chequers players making a move as he came out of the shop onto the porch where they were sitting. A bout of childhood polio had left the boy with a stutter and his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, had taught him that if he got stuck on a word to “just whistle, then go ahead and say it”. She always believed that was what her son had done that day. Whatever the reason, the whistle led to Till being so badly beaten that when his body was pulled from the river, he was identifiable only by his dead father’s signet ring which he wore. His murderers were acquitted on the spurious grounds that prosecutors had failed to prove “beyond reasonable doubt” that the body was Till’s. Bryant and Milam’s defence team (which was supported by counter-top jar collections in local stores) suggested another boy’s body had been dumped there in place of Till’s by “people in the United States who want to destroy the way of life of southern people”.

Jurors ignored Till’s relatives, who said they had heard a woman’s voice — believed to have been Carolyn Bryant’s — identify Till as Bryant and Milam pulled him from his bed and shone a torch in his face. They also dismissed claims that the lynch party had consisted of others waiting with Bryant’s wife by the red truck in which Till was then driven away. They paid no attention to two farm hands who testified they had seen Bryant and Milam with two of Milam’s black employees, and at least two other white men, in the same truck in the back of which Till was seen crouching as it sped towards the farm of one of Milam’s brothers. The same witnesses testified that “licks and hollering” were heard coming from a barn on the farm and that a large, heavy object wrapped in tarpaulin was later loaded back onto the truck and driven away.

Jurors never heard evidence from Milam’s two black employees, Henry Lee Loggins and Leroy “Too Tight” Collins, one of whom, it was said, was later seen washing blood from the back of the truck. The men, it emerged, had been kept locked at a secret destination by Sheriff Strider and intimidated into keeping quiet. When they were released, it was feared they too would be killed if they testified. So black activists — hoping to have the trial moved to a neighbouring county, where a less bigoted sheriff might permit a fairer trial — smuggled the men over the state border to Tennessee. Although Till’s body was found in Tallahatchie County, the barn to which witnesses testified he had been taken — and it was presumed killed — was in neighbouring Sunflower County. But the trial was never moved.

Had Loggins and Collins testified, however, it is unlikely it would have made any difference. In his summing-up, one defence attorney’s advice to the jury was that they should do their “Anglo-Saxon duty” and acquit Bryant and Milam. If the two men were convicted, the jury was told, “your forefathers will turn over in their graves”. After their acquittal, Bryant and Milam moved away from the area. Despite rejoicing by white spectators at the end of the trial, most customers at Bryant’s store had been black and they boycotted the business, forcing it to close. Bryant’s wife, now 70, divorced her husband, changed her name several times and kept on the move, first in California, then Florida. Till’s uncle’s family and other witnesses moved away too. Though the murder and subsequent sham trial remained a festering sore, few talked about it openly again in the community in which it happened, preferring to put it in the past.

For the past nine years, however, a young black documentary maker has been tracking down witnesses in the case: both those who testified and those who were never called. As Keith Beauchamp began piecing together his film, he also started touring the country giving previews of the material he was gathering to special-interest groups and state legislators, in an attempt to get them to support his conviction that the case should be reopened. Two years ago the veteran black film-maker Stanley Nelson made an award-winning documentary about the case and called on the attorney general’s office to reopen Till’s murder investigation. Yet in May, when the US Justice Department announced that the investigation was being reopened, a spasm of dread gripped some still living in and around Money, Mississippi. The community has now dwindled to isolated clusters of dwellings: the larger, stylish homes belonging to white farmers who have diversified from cotton into catfish farming and growing soya and corn, and the smaller red-brick bungalows of their black neighbours, who commute to the nearby town of Greenwood for what work they can find. Few appear to feel easy talking about what happened even now, nearly 50 years later. William Henley, a 72-year-old former field hand who lives close to the site of the cabin that once belonged to Till’s great-uncle, summed up the feelings of many of Money’s older black residents with his conclusion that “ain’t nothin’ much going to change in Mississippi by opening all this up again”. “What happened then could happen now,” says Henley, sitting under a thin awning outside his front door in the early evening rain. “It don’t take much to stir up bad feelings.”

Anniebell Hill, 64, who lives by the side of the railway track that winds through fields of cotton and corn, agrees. Hill still remembers listening to news of the trial of Till’s killers on the radio when she returned from working in the fields as a girl. “What good will it do now to put an old woman on trial?” she says referring to Bryant’s wife, who, it is thought, is the most likely to face charges. “I don’t think many people here think it’s a good idea… We get on fine with the white folk, don’t have no problems now.”

The reasons for such reluctance at the prospect of a fresh trial becomes clearer after speaking to some of the community’s white inhabitants about their attitudes now to what happened to Emmett Till. “I reckon he got what he deserved,” says Roy Petty, Money’s elderly part-time postmaster. “Maybe it got a little out o’ hand. Maybe it was a case of taking chivalry to the extreme. But Bryant was protecting his wife from insult and injury — from what we used to call ‘uppity niggers’. That boy was smarting off, grandstanding, and when they went to deal with it, he did the same to them, far’s I understand. In my opinion, if he had been contrite, he would have gotten away with a whippin’.”

Delmar Turney, 39, who lives next door to the ruins of Bryant’s old store, which some are now talking of turning into a museum, adds: “Like we say around here, if a dog does his business in the street and you leave it alone, it’ll smell a bit, but then you won’t pay it no heed. But if you poke it with a stick, the stink will come up again. Dragging this old case up will create such a stink, it will pit neighbour against neighbour.”

Ted Kalich, the editor of the Greenwood Commonwealth newspaper, in the nearest town to Money, also believes reopening the case could damage race relations in the area. “What is to be accomplished by going after the bit players now the two principal protagonists are dead? What are the chances of there being a fair trial 50 years after the fact?” he asks. Kalich admits to “mixed feelings” about the prospect of a new trial. While conceding the historical significance, he believes it could end up as an exercise in “beating up on Mississippi”. “Mississippi in 2004 is not what it was in 1955,” he stresses, pointing to the fact that 47 of the state’s 174 legislators are now black. But one of those legislators, David Jordan, a 70-year-old Mississippi state senator who lobbied hard for the case to be reopened, stresses that while some things have changed in the delta, much has not. As we drive through an affluent northern neighbourhood of Greenwood, Jordan remembers that when he was a boy in the 1940s, no blacks could walk the streets here unless they were wearing worker’s overalls, showing they had come to provide some service to white residents.

Jordan was the first in his family to escape such servitude. He had just started college at the time of the murder trial and was among the handful of black spectators — allowed in, he believes, because he was wearing a shirt and tie, not work overalls. “Few people who know about what happened to Emmett Till want to talk about it now,” he says. “But unless there’s a fair trial, this thing will never end.” As we drive, Jordan, a former science teacher, points out Greenwood’s private Pillow Academy, where pupils are almost exclusively white. Despite desegregation of the school system, pupils in the town’s state schools are overwhelmingly black.

“The [Ku Klux] Klan still exist in splinter groups here,” he says. “If you make too many waves you still get harassed.” When Jordan publicly backed a black candidate for the post of lieutenant governor recently, he had eggs thrown at his wife’s car. He also had the windows of his home broken several times. Whether a new trial will aggravate such attitudes or expose them and lead to change remains uncertain. “Perhaps the state of Mississippi will eventually reap the greatest benefit from a new trial, if it’s clearly and unequivocally fair,” said a Washington insider. “Perhaps it will rid itself once and for all of its image as a lynch-mob society.”

But for many, questions of image are beside the point. “There is no statute of limitations on murder. Justice was never done. As time has gone by, people have become more willing to talk, and now is the time to try to bring closure to this terrible crime,” stresses Hilary Shelton, director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

The reopening of the Till case should also be viewed, Shelton argues, in the context of a wider reckoning with the south’s murderous past. In the past 15 years, nearly two dozen “cold cases” from the civil-rights era have been reinvestigated, many leading to successful prosecutions. Among the highest-profile of these was the 1994 conviction of Byron de la Beckwith for the murder of the civil-rights leader Medgar Evers in 1963. Two years ago, a 72-year-old former Ku Klux Klansman, Bobby Frank Cherry, was finally convicted for the murder of four black schoolgirls in the 1963 bombing of an Alabama Baptist church.Two weeks after the announcement that Till’s case was being reopened, the justice department was also called on to help reinvestigate the killing of three civil-rights workers in Neshoba County, Mississippi, during the 1964 “freedom summer” drive to register black voters. The murder of Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner — both civil-rights workers from New York — and James Chaney, a local black activist, was portrayed in Alan Parker’s 1988 film Mississippi Burning. But Mississippi’s attorney general has recently expressed doubt about whether there’s enough fresh evidence to continue pursuing the case.

Mark Potok of the Southern Poverty Law Center, a civil-rights advocacy group based in Alabama, believes the Emmett Till murder could be the end of an era as far as reopening old civil-rights cases is concerned. He believes the move is particularly significant as America is now facing a resurgent neo-Confederate movement. “There is still a vast swathe of white America that refuses to believe what occurred in the south,” says Potok. “These are people who continue to describe the antebellum and postbellum period here as some kind of Garden of Eden, when the reality was, it was a society based largely on violence and the threat of terrorist murder. I hope these cases will help lodge that fact in the American mind.”

While welcoming the initiative to reopen the case, Potok is cynical of the current administration’s motivation for doing so. “Whether this is based on new evidence or is an attempt by Bush to look good before the election is unclear to me. I think the latter is a clear possibility, which is rather disgusting.”

Keith Beauchamp, 32, is quick to dismiss such scepticism. “Even if this is being done for political reasons, we have to take the ball and run with it,” he says. “This is the last opportunity we are going to have to see justice done.” Till’s mother, who died last year, fought all her life, he stresses, to have the case brought before a just court. Beauchamp believes there are at least five people still alive — including Carolyn Bryant, Loggins and “Too Tight” Collins — who need to be held accountable for the part it is alleged they played in the boy’s murder.

The seasoned film-maker Stanley Nelson is more sensitive to the repercussions a new trial could have for the locals. “The power structure in Mississippi is still in many ways what it was. The economy is still controlled by white landowners who operate a feudal system. Many African-Americans live on their land and buy their food on credit, and if someone testifies even today, they could find themselves the victim of a backlash.” But there comes a time, says Nelson, when everyone has to examine his or her own conscience and do what is right. “And in the case of Emmett Till,” he says “that time is long overdue.” As Bob Dylan wrote in his ballad The Death of Emmett Till, released in 1963,the year of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech and a time of particularly brutal and frequent Ku Klux Klan activity in the south, “If you can’t speak out against this kind of thing / A crime that’s so unjust / Your eyes are filled with dead men’s dirt / Your mind is filled with dust.”