August 28, 2005

August 28, 2005

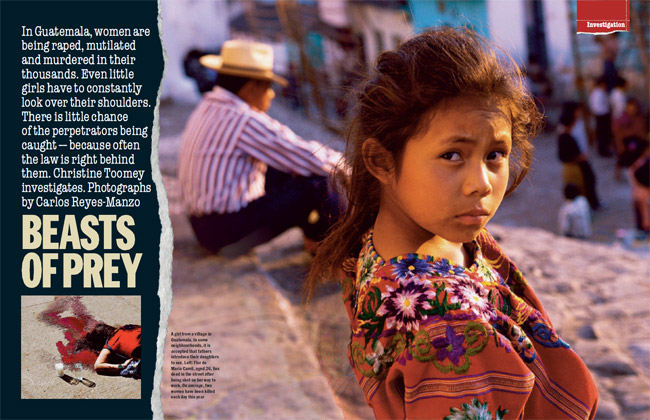

In Guatemala, women are being raped, mutilated and murdered in their thousands. Even little girls have to constantly look over their shoulders. There is little chance of the perpetrators being caught — because often the law is right behind them. Christine Toomey investigates. Photographs by Carlos Reyes-Manzo

There is a country where a man can escape a rape charge if he marries his victim — providing she is over the age of 12. In this country, having sex with a minor is only an offence if the girl can prove she is “honest” and did not act provocatively. Here, a battered wife can only prosecute her husband if her injuries are visible for more than 10 days. Here too it is accepted in some communities that fathers “introduce” their daughters to sex.

In this country the body of a girl barely into her teens, or a mother, or a student, can be found trussed with barbed wire, horrifically mutilated, insults carved into her flesh, raped, murdered, beheaded and dumped on a roadside. In its capital city, barely a day goes by without another corpse being found. Bodies are appearing at an average of two a day this year: 312 in the first five months, adding to the 1,500 females raped, tortured and murdered in the past four years.

This country is Guatemala, and to be a woman here is to be considered prey. Prey to murderers who know they stand little chance of being caught. Prey not just on the street, nor at night, nor in back alleys, but in their homes, outside offices, in broad daylight. In Guatemala someone has declared war on women. Someone has decreed it doesn’t matter that so many are dying in grotesque circumstances. Someone has decided that if a woman or a girl is found dead she must have asked for it, she must be a prostitute, too insignificant to warrant investigation. Everyone here knows women are being murdered on a huge scale, and not by one serial killer, nor two nor even three, but by a culture. So why is this happening? Why is it being allowed to continue?

* * * * *

Manuela Sachaz was no prostitute. She was a baby-sitter, newly arrived in the city to care for the 10-month-old son of a working couple. They found her body on the floor in a pool of blood. The baby was propped up in a high chair, his breakfast still on the table in front of him. Both had been beheaded. The nanny had been raped and mutilated; her breasts and lips had been cut off, her legs slashed.

Maria Isabel Veliz was just a happy teenage girl with a part-time job in a shop. She was found lying face down on wasteland to the west of the capital. Her hands and feet had been tied with barbed wire. She had been raped and stabbed; there was a rope around her neck, her face was disfigured from being punched, her body was punctured with small holes, her hair had been cut short and all her nails had been bent back.

Nancy Peralta was a 30-year-old accountancy student who failed to return home from university. She was found stabbed 48 times; her killer or killers had tried to cut off her head.

But you have to dig deep to find the families and talk to their neighbours and friends to learn about the terrible things that are happening in this small Central American country sandwiched between Mexico and El Salvador.

Newspapers here carry a daily tally of the number of female corpses found strewn in the streets, but such discoveries are usually considered so insignificant they are relegated to a sentence or paragraph at the bottom of an inside page. Brief mention may be made of whether the woman has been scalped, tortured, decapitated, dismembered, trussed naked in barbed wire, abandoned on wasteland or, as is common, dumped in empty oil drums that serve as giant rubbish bins. Some reports might mention that “death to bitches” has been carved on the women’s bodies, though there is rarely a mention of whether the woman or girl, some as young as eight or nine, has been raped. According to Dr Mario Guerra, director of Guatemala City’s central morgue, the majority have. Many of the women are simply designated “XX”, or “identity unknown”. This is because they have often been taken far from the place where they were abducted and subjected to unimaginable tortures before being killed. It can take the women’s families days, weeks or months to trace them. Many are unrecognisable and, as there is no DNA profiling here, some are never claimed and simply buried in unmarked communal graves.

* * * * *

To truly understand what is happening in this country and what happened to Manuela, Maria Isabel or Nancy, you have to spend a few moments stepping back in time to the darkest days of Guatemala’s 30-year civil war. The slaughter began earlier here and lasted much longer than in El Salvador and neighbouring Nicaragua, though it escalated for similar reasons. It escalated because, in the context of the cold war, successive United States administrations felt threatened by the election of liberal and socialist governments in the region and the emergence of left-wing guerrilla insurgencies. Often secretly, they proceeded to pump massive military aid into these countries’ armed forces and right-wing rebels to fight the leftists — though in the case of Guatemala, what happened was a more blatant case of protecting US corporate interests.

By the early 1950s, vast swathes of Guatemala lay in the hands of America’s United Fruit Company. In 1954, when the country’s left-leaning government started expropriating some of this land to distribute to the poor, the CIA, whose director had financial ties to the company, orchestrated a military coup. Land reform stopped, left-wing guerrilla groups began to form and the US-sponsored anti-insurgency campaign began. The 30-year cycle of repression that followed, reaching its bloodiest peak in the 1980s, was the most violent, though least reported, in Latin America. Large areas of the countryside were razed, their population, mostly Mayan Indian, massacred. Villagers were herded into churches and burnt, whole families sealed alive in wells. Political opponents were assassinated, women were raped before being mutilated and killed. The wombs of pregnant women were cut open and foetuses strung from trees. By the time the UN brokered a peace deal in 1996, over 200,000 had been killed, 40,000 “disappeared” and 1.3m had fled their homes, to leave the country or become internal refugees. This in a country with a population of little over 10m.

When the Catholic Church concluded in 1998 that 93% of those killed (in what were later recognised as “acts of genocide”) had perished at the hands of the country’s armed forces, paramilitary death squads and the police, the bishop who wrote the report was bludgeoned to death on his doorstep. Unusually, given the country’s climate of almost complete impunity, three army officers were convicted of his murder.

In recognition that it was those the US had armed, and in part trained in methods of sadistic repression, who were responsible for most of the atrocities, the UN-sponsored peace deal demanded that the country’s armed forces and police be reduced and reformed. It also demanded that those responsible for the worst atrocities be brought to justice. Not only did this not happen, but Efrian Rios Montt, the general accused of acts of genocide at the height of the war (charges famously dismissed by the former US president Ronald Reagan as a “bum rap”), subsequently stood for president. Though he failed in this bid, he was eventually elected president of Congress — a position similar to the Speaker of the House. And while the army and police force were pared down, and in the case of the police their uniforms updated, the men did not change. In a land that has seen such lawless atrocity go unpunished, it is not surprising that life should be cheap. And in a land where the culture of machismo is so pronounced, it is not surprising that men have become accustomed to thinking they can murder, torture and rape women with impunity.

This is not, of course, how the police here see it. It is astonishing how quickly the police chief Mendez, in charge of a special unit set up last year to investigate the murder of women, agrees to see me. Considering his workload, you would think he was a busy man. But when I call to make an appointment I’m told he can see me at any time. The reason for this courtesy quickly becomes apparent. Not a lot seems to going on in Mendez’s office; his unit appears to be little more than window-dressing. Tucked away in a low building on the roof of the National Civil Police HQ in the heart of the capital, the office looks almost vacant; four desks sit in the far corners of the sparsely furnished room, separated by a row of filing cabinets. The only wall decoration is a large chart of the human body “to help police officers write up their reports of injuries inflicted on murder victims”. There are four computers, only two of which are switched on. Apart from Mendez and his secretary, there are three other police officials in the room at the time of my visit. All sit huddled in a corner chatting and laughing throughout the interview.

When asked what he believes lies at the root of such extraordinary violence towards women in Guatemala, Mendez repeats a mantra that seems to be widely held as normal: “Women are coming out of their homes and participating in all aspects of society more. Many men hate them for this.” He adds, as if it were necessary, that “this is a country with many machistas [male chauvinists]”. It is difficult to interpret the latter as a complaint, however, when the police chief’s young secretary is standing behind him in an overtight uniform, stroking his hair as we speak.

Mendez attributes the general climate of violence to burgeoning drug-trafficking, the proliferation of illegal arms and to vicious infighting between rival street gangs — known here as maras, after a breed of swarming ants. In a country with at least 1.5m unregistered firearms, which last year alone imported an estimated 84m rounds of ammunition, this is a large part of the picture. Guatemala City is now one of the deadliest cities in the world, with a per-capita murder rate five times higher than even Bogota in war-torn Colombia. The police chief taints this overview, however, by suggesting that one way of tackling the problem would be to get rid of the bothersome legal presumption of innocence when arresting suspects.

Given such attitudes, it is hardly surprising that less than 10% of the murders of women have been investigated. Even less so when you consider the case of 19-year-old Manuela and the baby, Anthony Hernandez, in her care.

In the vicinity of the small apartment that baby’s parents, Monica and Erwin Hernandez, shared with their son and the baby-sitter, on the second floor of an apartment block in the Villa Nueva district of Guatemala City, there lived a middle-aged police officer. Clutching a photo of her grandson and struggling to talk through her tears, Cervelia Roldan recalls how the baby’s mother, Monica, came looking for her after she finished work on the Wednesday before Easter last year. “She asked me if I had seen Manuela, because she wasn’t opening the apartment door and my daughter-in-law didn’t have a key. We went back to the apartment together and started calling out Manuela’s name, but there was no answer. Then that man, the policeman, came to the front door of his apartment block. It was about five in the afternoon, but he was wearing just his dressing gown. He seemed very agitated and told us to look for Manuela in the market.”

When Cervelia’s son went back to his apartment a short while later with his wife and mother and still nobody answered their calls, he broke a window to open the apartment door. He found the body of the baby-sitter and their child inside. Three days later the policeman shaved off his beard and moved away. “Neighbours told me later how he used to pester Manuela,” says Cervelia, who claims that after the double murder, Manuela’s bloodstained clothing was found in his house. The authorities dispute this: they say the blood on the clothing does not match that of the baby or his nanny. Cervelia, however, says she has seen the policeman in the neighbourhood several times since the killings. “He laughs in my face,” she says. “What I want is justice, but what do we have if we can’t rely on the support of the law?”

It is a burning question. Of the 527 murders of women and girls last year, only one of these deaths has resulted in a prosecution. And what explains the extreme savagery to which female, yet few male, murder victims are subjected? Nearly 40% of those killed are registered as housewives and over 20% as students. Yet according to Mendez, the hallmark mutilations of women killed are the result of “satanic rituals” that form initiation ceremonies for new gang members. The overwhelming impression given by the government is that gangs are to blame for most of the killings. A spokesman for the Public Ministry — the equivalent of the Home Office — where the file on the murder of Anthony Hernandez and Manuela Sachaz now languishes, claims they could have been murdered because Manuela was a gang member, even though the teenager had only recently arrived in the capital from the countryside to work as a baby-sitter.

In the poorest barrios of Guatemala City, where gangs proliferate, gang members — known as pandilleros — admit some women are caught up in inter-gang rivalry. “But a lot of women are being murdered so police can blame their deaths on us and kill us indiscriminately,” said one heavily tattooed 19-year-old slouched against a wall in a neighbourhood where the headless corpse of a young woman had been found a few hours previously. “The police only have to see a group of two or more of us with tattoos hanging about and they start shooting.”

We witnessed this first-hand. Within minutes of arriving in this neighbourhood to speak to members of the country’s largest gang, the Mara Salvatrucha, two squad cars came screeching across the rail tracks, police jumped from their cars, cocked their rifles and ordered the youths to brace themselves against the walls. According to the police, a “concerned” member of the community had called them, worried about the presence of strangers — the photographer Carlos Reyes and me — in their midst. This seems unlikely. A likelier scenario is that the police were tipped off that a group of pandilleros was gathering. Had we not been there, the gang members are convinced they would have been shot. Had this happened, there would almost certainly have been no investigation. For, since the end of the civil war, organised crime networks that have infiltrated the government, the army and the police at every level, recruit gang members to do their dirty work, then murder them — both to eliminate witnesses and “socially cleanse” the streets of those regarded as a common scourge.

Human-rights workers, who are regularly subjected to death threats and intimidation, also say blaming the murder rate on gang violence is a deliberate oversimplification of the problem. Women, they say, are not only being “killed like flies” because they are considered of no worth, but they are also being used as pawns in power struggles between competing organised crime networks. “A key element in the history of Guatemala is the use of violence against women to terrorise the population,” explains Eda Gaviola, director of the Centre for Legal Action on Human Rights (CALDH). “Those who profit from this state of terror are the organised criminals involved in everything from narco-trafficking to the illegal adoption racket, money-laundering and kidnapping. There are clear signs of connections between such activities and the military, police and private security companies, which many ex-army and police officers joined when their forces were cut back.”

Earlier this year, the ombudsman’s office issued a report saying it had received information implicating 639 police officers in criminal activities in the past 12 months, and that it had opened cases against 383 of those, who were charged with crimes ranging from extortion and robbery to rape and murder. Given that most of the population is afraid to report crimes, this figure is almost certain to be a considerable underestimate of police complicity.

Three years ago, Amnesty International labelled Guatemala “a corporate Mafia state” controlled by “hidden powers” made up of an “unholy alliance between traditional sectors of the oligarchy, some new entrepreneurs, the police, military and common criminals”. Today, to coincide with the publication of this article, Amnesty is launching a protest appeal on its website to form a petition of those appalled

by what is happening to women in Guatemala. This will be presented to the country’s president, in an effort to put international pressure on authorities in the country to take action to stop it. Without such pressure, few believe the government will take the problem seriously.

For Guatemala is a small country, condemned by its geography to relative obscurity. In neighbouring Mexico, in Ciudad Juarez, a city that sits on the northern border with the US, the murder of over 300 women in the past decade has drawn international attention. Film stars such as Jane Fonda and Sally Field, accompanied by busloads of female students from around the world calling themselves “vagina warriors”, have marched into town for special performances of The Vagina Monologues, to highlight and denounce what has been dubbed “femicide”. Yet here, few pay any heed to what is happening.

An attempt by the UN to set up a commission with powers to investigate and prosecute the country’s “hidden powers” — expected to serve as a model for other post-conflict countries — has been dismissed by the Guatemalan authorities as “unconstitutional”. There is now a debate about how the terms of the commission can be amended to make it acceptable. But as the talking continues, so does the killing.

* * * * *

Rosa Franco has been fighting for the past four years for the authorities to investigate the murder of her teenage daughter Maria Isabel. Surrounded by photos of the girl wearing a white dress with flowers in her hair at a church service to celebrate her 15th birthday, Rosa hands me some notes her daughter wrote her before she was killed — a few months after these photos were taken. They are the tender notes of a teenager with deep religious faith. “Sometimes my daughter would visit me at work and pretend she needed to use my computer for her homework. But what she really wanted was to leave me a note telling me how much she loved me,” says Rosa, a secretary who had been studying for a law degree before Maria Isabel died in mid-December 2001. “She was proud of what I was trying to do,” says Rosa, who was left to raise her daughter and two younger sons alone after their father left them. One of the notes, written on Valentine’s Day of that year, tells her mother to “always look ahead and up, never down”. This has been an almost impossible task since the day her daughter disappeared.

Rosa remembers every detail of that day. “As usual, she did not want breakfast — she wanted to stay thin — though I persuaded her to have a bowl of cornflakes before she left for work. I had given my daughter permission to work in a shop during the Christmas holidays, as she wanted to buy herself some new clothes. I wasn’t well that day and went to sleep early. When I woke up the next day and my daughter wasn’t there, I went to the police to report her missing. They said she’d probably run away with a boyfriend.”

That night, while watching a round-up of the news, Rosa recognised, from the clothing Maria Isabel had been wearing when she left for work the day before, the body of her daughter lying face-down on wasteland to the west of the capital. When she went to the morgue and discovered the brutality to which her daughter had been submitted, she lost consciousness. “When I collapsed, they told me not to get so worked up,” says Rosa, who later suffered a heart attack. When Rosa began pushing the police to find her daughter’s killers, presenting them with records that the girl’s mobile phone had been used after her death, and tracking down witnesses who gave descriptions of the girl being pulled from a car, the authorities accused her of meddling and dismissed her daughter publicly as a prostitute.

Such smear campaigns are used to intimidate the families of female murder victims. A spate of killings of prostitutes was given prominent media coverage after the police started compiling statistics according to the sex of murder victims four years ago; it was only then that the scale of violent deaths among women emerged.

Undeterred by this tactic, Rosa has continued to demand justice — and the intimidation has increased. Her teenage sons are often followed home from school. Cars with several occupants watching her house sit a short distance from her home in regular rotation — one is there the night we sit talking in her living room. Human-rights workers say such surveillance is a mark that the murder has a connection with officialdom and organised crime. “I’m afraid,” Rosa says. “But when I see reports of more and more murders of girls and women, I know what other mothers are going through. I vow I will not give up my fight.”

It is a sentiment shared by two sisters, Maria Elena and Liliana Peralta, whose elder sister, Nancy, was killed just a few months after Maria Isabel. When the sisters and their parents reported that the 30-year-old accountancy student had not returned home from university in February 2002, they were told by police to come back in a few days if she didn’t turn up. The next day, their father read about the body of an unidentified young woman being found on the outskirts of the capital. When he rang the morgue he was told it could not be that of his daughter, as the physical description of her did not match, though one item of clothing she had been wearing when she left home was the same as that on the body recovered. When the sisters’ father went to the morgue to check, he found his daughter had not only been killed, but her body had been horrifically mutilated.

“When I talk to the police, they jokingly refer to my sister as ‘the living dead’. They insisted she had not died, as some other student had assumed her identity to enrol on a new university course. They showed no interest in investigating what had happened,” says Maria Elena, who is now studying law to bring her sister’s killers to justice.

One of the complaints of Rosa Franco and the Peralta family is that even the most basic forensic tests, such as those of body fluids, that may help identify the murderers in both cases were never carried out at the morgue. Its director, Dr Guerra, argues that his efforts to contribute to criminal investigations are hampered by the lack of a forensic laboratory on site and the absence of DNA-testing facilities in the country; samples, when taken, have to be flown to Costa Rica or Mexico for analysis. “Until a few years ago, the US helped train our workers in forensic science,” says Guerra. “But now that help has stopped.”

Convinced they are being thwarted by the Guatemalan authorities, Rosa Franco and the Peralta family are considering taking their cases to the Inter-American Commission. But most victims’ families have neither the resources nor the know-how to launch a legal fight. Instead they sit in queues waiting to talk to human-rights workers and beg for news about what is being done to bring those who killed their loved ones to justice. The usual answer is nothing.

On just one day in June, these queues included Catalina Macario, the mother of 12-year-old Hilda, who had been eviscerated with a machete for resisting rape — Hilda survived, but was shunned by her community because of the stigma attached to sexual violence — and Maria Alma de Villatoro, whose 21-year-old daughter, Priscilla, was stabbed to death by her boyfriend for refusing to have an abortion.

“Women here are dying worse than animals. When the municipality announced this summer that it was launching a campaign to exterminate stray dogs, the public took to the streets in protest and it was stopped,” says Andrea Barrios of CALDH. “But there is a great deal of indifference towards the murder of women, because a picture has been painted that those who die somehow deserve what they get.”

“Neither the police nor the government are taking this seriously. Yet what we are observing is pure hatred against women in the way they are killed, raped, tortured and mutilated,” says Hilda Morales, the lawyer heading a network of women’s groups formed as the problem has escalated. The situation is unlikely to change, she argues, unless international pressure is brought to bear and foreign investors are made aware of what is going on in the country and start questioning their business dealings there.

Claudia Samayoa, another member of the network, says: “Fifty years ago, the UN signed a declaration decreeing we all have certain basic human rights . With so much conflict in the world, if anyone were to say a choice must be made between helping us and helping those in Darfur, we’d say help Darfur. But how does the international community make such selections? What are the agreements they sponsor worth if there is no follow-through to ensure they’re met?”

Far removed from the mayhem of modern-day Guatemala City, in the country’s northern rainforest, rich with remains of pre-Colombian Mayan civilisation, archeologists entering a long-sealed crypt recently stumbled upon an ancient murder scene. The remains of two women, one pregnant, were arranged in a ritual fashion: the result, it was said, of a power struggle between rival Mayan cities. More than a millennium-and-a-half later, the women of Guatemala are still being slaughtered as part of a savage power play.

To register your protest, visit: www.amnesty.org.uk