March 10, 2007

March 10, 2007

Investigation

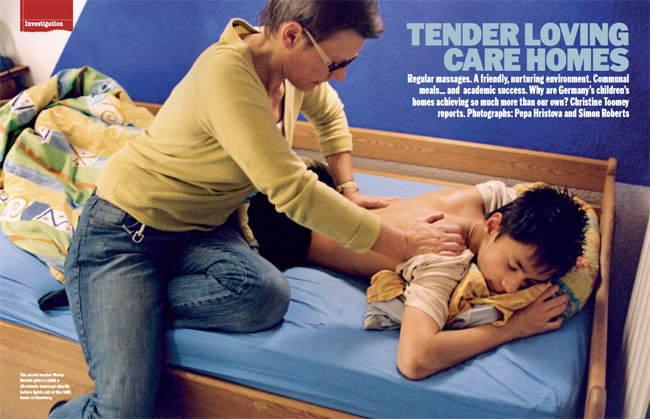

Regular massages. A friendly, nurturing environment. Communal meals… and academic success. Why are Germany’s children’s homes achieving so much more than our own? Christine Toomey reports. Photographs: Pepa Hristova and Simon Roberts

The moment of the day children most look forward to in one children’s home in the heart of Hamburg is just before lights out, when they are asked if they want a massage. Most do. So for 10 or 15 minutes, each child will have his or her back and shoulders rubbed by whichever female social workers are on duty. “It’s the most relaxing part of the day. I love it,” says 15-year-old Janina, who on her own admission was so aggressive before she came to live in the home six years ago, she used to spit at her mother and chew the carpet.

For the six older children like Janina in their mid- to late teens, all of whom have been living in the home for six to eight years, these moments of calm come in the hour before 10pm. For the younger children it is earlier: their lights are turned off at 8.30pm. Everything in this comfortable, colourfully furnished four-storey house in Hamburg’s central Schanzen district runs like clockwork: lunch is at 1.15, homework between 2.30 and 4pm; teeth are brushed at a certain time. But this is where such strict order ends. Every other aspect of the children’s lives, particularly their emotional welfare and contact with their families, is handled with emphasis on their individual needs.

Younger children, who have arrived more recently and might be coping with fresh traumas or consequences of abuse, are also offered nightly massages. “But I will make a game of it: run a toy car across their shoulders or pretend I’m kneading dough to make a pizza on their backs,” says Maria Nemitz, a social worker who has worked at the home – known by its initials, SME – for 16 years. “We have no problem with physical contact with the children,” she adds. “Some have had such negative experiences, we need to help them learn to trust again, and this includes trusting being touched by another person.”

When I relate this ritual to the manager of a local-authority-run children’s home in London’s Hammersmith, he nods. “There is clearly some serious therapeutic work being done there,” says Philip Craig, who for the past six years has managed the Dalling Road home, designated an “emergency unit” by Hammersmith and Fulham council, which houses up to 10 children for periods of up to three months. Yet when I mention the routine to one of Craig’s part-time workers, she says most staff at Dalling Road would “shudder at the thought” of being asked to give the children a massage. “There are all sorts of child-protection issues involved,” says Norma Mann. “We wouldn’t chance it. In everything we do, we work according to strict protocols.”

To emphasise this point, I am shown two ring folders bulging with statutory regulations and policies. One contains 47 separate procedures, ranging from how to deal with bullying, discrimination and substance abuse, to what to do if a child tries to make contact with a member of staff once they have left Dalling Road (in short, the advice is “Don’t allow it”).

Staff are expected to keep three simultaneous daily logs. The first is a handwritten diary noting the movement of staff and children in and out of the home; no Tipp-Ex corrections are allowed and all unused parts of pages must be crossed through and initialled. The second is a round-the-clock record of the children’s activities and staff registering, for instance, if a child gets up for a glass of water in the night. The third is an individual log compiled each day for each child, noting their activities and behaviour. All these logs and diaries must be stored for a minimum of 75 years – partly in case a child makes an allegation of abuse against a care worker. So many need to be held onto that thousands are kept at a disused salt mine in Kent.

“What these procedures do,” says Craig, “is offer a form of safety for staff. If you work outside of procedure and an allegation is made against you by a child or family member and you have nothing to refer to, chances are you’ll be hung, drawn and quartered. But sometimes we get so caught up with procedures, we lose sight of the child,” says Craig, who describes this pressure of paperwork as “a nightmare”. Add to this climate of paranoia the government’s obsession with progress targets and performance indicators, and what Craig concludes seems self-evident: “Many senior managers in this field are more interested in reports, statistics and numbers than the individual needs of the children we look after.”

Many would assume that a childcare institution in Germany would be run along more bureaucratic lines than one here. But it is to throw light on one of the most shameful records to which this country can now claim that I visit Dalling Road and SME. This is that, compared with other countries in Europe, when it comes to children in care – “looked-after children” as they are now called in the UK – those here face the bleakest of futures.

Despite the amount spent annually on the 60,000 children, on average, looked after each year in this country having doubled to nearly £2 billion in the past decade, both their short- and long-term prospects are devastating. In 2005 only 11% of those in care attained five GCSEs at grade A-C, compared with 56% of all children (59% of children in care were not entered for GCSEs at all). Of the 6,000 who leave care on average each year, many experience mental-health problems, drug and alcohol addiction, and end up on the streets (one-third of this country’s homeless were raised in care). Fifty per cent find themselves unemployed within two years. A quarter of girls are pregnant when they leave care and half become single mothers within two years.

In Germany, where fewer statistics are kept, it is estimated that three-quarters of those in care pass the General Certificate of Education taken at 16 and 95% go on to vocational training. Only 2% of children in care under 16 are out of school (in the UK it is 12%) and less than a quarter of those over 16 are neither in employment nor education (here it is 55%). As a result, fewer resort to crime; children in care in Germany commit on average 0.09 offences a year compared with 1.73 committed by those here. In the UK, 60% of young offenders and 27% of the adult prison population have been through the care system.

While statistics only offer a glimpse of reality, the stark differences in all of the above have so embarrassed this government that in the last year senior ministers have made several pilgrimages to care homes in Germany and the Netherlands, to see what they are getting right and what we are getting so wrong. Some of the lessons learnt are included in the green paper called Care Matters – a wide-ranging package of proposals aimed at improving the lives of children in care.

Unveiling the package last October, the education secretary, Alan Johnson, conceded it “inexcusable and shameful that the care system seems all too often to reinforce early disadvantage rather than helping children to successfully overcome it. Our goals for children in care should be exactly the same as our goals for our own children. We want their childhoods to be secure, healthy and enjoyable… providing stable foundations for the rest of their lives. Fine words. But will it work?

It is not the government’s first attempt to tackle the problem. In the wake of the appalling death of Victoria Climbié in 2000, an initiative called Every Child Matters was forged to better co-ordinate children’s services through the work of GPs, health visitors, social workers and schools. This latest package is more far-reaching when it comes to older children. A significant change being proposed is that children will be able to veto any decision that they leave care before they are 18, with some given the option to live with foster families until they are 21. At present, many are left to fend for themselves once they reach 16.

There are also plans to pay set salaries and provide training for some foster carers (British ministers visiting care homes abroad have been particularly influenced by the training there of those working with children.) To improve the education of children in care, the green paper proposes that every local authority appoint a “virtual head teacher” to monitor their progress and promote them being admitted to the best schools available. Moving children around from the care of one local authority to another – frequently to save money – would become harder to do.

But many believe a more fundamental change is needed – a change that involves us all: a profound shift not only in how we view and support those who work with children in care, but also how we view the children they look after. Otherwise we will continue to be marked by the dubious distinction of being one of the richest European countries to educate its most vulnerable children to the lowest standard, see more become homeless, fall prone to mental illness and serve repeated spells in jail. Those who observe us from abroad believe much of our problem lies in the peculiar harshness with which we in this country view childhood in general. Untangling a society’s attitude towards its children is a complex affair. But what those at SME, Dalling Road and a privately run children’s home in West Sussex have to say exposes some sobering realities.

Rudiger Kühn has spent the past 22 years working with children referred by the city of Hamburg to the care of the SME home he now manages. SME had been open for only a few years when he started working there in the early 1980s. Just as in the UK, Germany underwent a rethink in the late 1970s and early ’80s of the way children in care should be looked after. As in the UK, large institutional-type homes where children led regimented lives in long dormitories were closed and alternative forms of care were sought. This is where much of the similarity between the UK and Germany ends.

The alternative the UK developed was foster care supplemented by smaller children’s homes regarded as a last resort for children for whom foster families either could not be found or were not thought suitable. Two-thirds of all children in care in this country are now fostered. Fostering was promoted because it was thought that children would thrive best in families. How important a factor money was in developing this policy is debatable. But the fact is, fostering is on average four times less expensive than residential care, where the cost of looking after a child can run from £1,500 to £3,500 a week.

Germany moved in the opposite direction. There fostering is seen as a last resort. Over two-thirds of children in care are looked after in residential homes, most of them relatively small like SME, which caters for 16 children. Most children who are fostered in Germany are those who it is believed are unlikely to be able to have a successful relationship with their own family. Though many feel residential care lays the child open to being institutionalised, after listening to the experiences of Kühn and the children in his care, this approach begins to make sense.

Janina did live with a foster family before coming to SME, and is in no doubt which she prefers. “I had my own family. I had a mother, even if she and I didn’t get on. I didn’t like being put in another family where I was forced into close relations with complete strangers,” says the teenager as she perches on the edge of her bed surrounded by posters of her pop idols and school books. “I prefer living here. I feel more free. If I have an argument with someone here, there’s enough space for one of us to get out of the way. I still see my mother a lot, but here everything’s more ordered; they help you with your school work. When I finish school, I hope to move back to live with my mother.”

Janina’s view is echoed by other children whose families live close to the home. For Kühn and his co-workers, this seems completely natural. In foster families they say there are serious issues of split loyalties. “We often find children feel they are somehow betraying their natural parents by living with another family,” says Kühn. “As a result, the children behave as if they do not have permission to be successful.”

Kühn and his staff spend a great deal of time promoting good relations with the families of the children in their care. “We accompany our children for just a piece of their life, show them how they can live in a different way in the hope that they will take something of this with them when they leave, either to return to live with their families or to live independently,” says Maria Nemitz, explaining that great emphasis is placed on homework. The extent to which all the children at SME stress how determined they are to do well at school bears this out.

There are also historical reasons why children in Germany are fostered less frequently than here. This is because parental rights there are considered stronger. These rights were enshrined in the German constitution to counter the threat of totalitarianism in the country’s past by strengthening the power of the individual. Most parents in Germany, for instance, retain their parental rights even if their child is in residential care. Also in the wake of Nazism much emphasis was placed on developing a system of education and care for children that ensured teachers and others with educational responsibilities be as highly qualified as possible, partly to impress on children the need to be good citizens.

The reasons children are taken into care in Germany are similar to those here: most because of abuse or neglect, a smaller number because of family dysfunction, such as absent parents or a child’s socially unacceptable behaviour. Yet the stigma children in care suffer in Britain does not seem to be the same in Germany. In Germany there is a much greater sense that there are educational and therapeutic reasons, rather than reasons of protection, for a child being there. This partly explains why children stay on average three times longer in residential care in Germany compared with this country, and why the proportion of children in care there is higher: 65 per 10,000 young people compared with 44 per 10,000 in the UK. Some argue that this higher proportion of children in care in Germany means those in the UK come from more extreme circumstances. But after hearing what the children at SME say about their backgrounds, this hardly seems the case.

In a room alongside Janina lives Johana, 17, who together with an older brother has been living at the home since she was eight. Johana talks about how she first ran away from home at six, after witnessing her elder sister being raped by her stepfather. Ulaf, 15, talks of how his father could not cope when his mother walked out on the family home when he was nine. Two floors below, 13-year-old Patrizia, whose mother suffers mental-health problems, admits to getting into trouble for aggressive behaviour. Zara, 14, who shares a room with her, says she came to live at SME last year after being beaten up by an elder brother.

Joachim Genuneit, 50, who has worked at SME for the past 24 years, says: “At first, many parents whose children come here regard this place as a sort of workshop where their broken kids can be repaired. While the kids themselves think they have been sent here because there is something wrong with them, and they are being punished. But we work with parents and children to help both understand we are here to show them a different way of life is possible. We always emphasise it is the natural parents who are the most important people in a child’s life.”

Like the UK, Germany has had shocking instances of child abuse exposed. “The reaction of the German public when these happen is it wants its children protected, whatever it takes. Few questions are asked about cost, especially in a city like Hamburg, which is booming,” explains Dr Herbert Wiedermann, who oversees children’s services for the city authorities. “We take the attitude that if something has gone wrong in a family, there are external reasons, and we trust the professionals to help solve them. In the UK, it seems both children and their parents are seen as good or bad, and if they’re bad they’re punished. The UK policy of handing out Asbos would be unthinkable in Germany.”

Such a vote of public confidence in those who work with children in care can only be dreamt of here. “In countries like Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands, working with children in care, particularly in a residential setting, is seen as a plum job. Not here – hence the reliance in many places on agency staff,” says Professor Pat Petrie of London University’s Thomas Coram Research Unit, which was commissioned by the government to make a study of how work with children in care in the UK compares with that of other European countries.

This study highlights staff training, approach and commitment as key to determining whether the long-term prospects of looking after children were positive or not. In continental Europe, a whole profession exists that does not here: social pedagogy. This is considered much broader than social work and puts more emphasis on education and a deeper psychological understanding of a child’s development. By employing more highly trained staff, children’s homes in countries like Germany can function with fewer workers. SME, for instance, has nine members of staff for 16 children, while Dalling Road has 18 members of staff for 10 children. More highly trained staff also results in lower staff turnover (18% in Germany compared with 27% here), which means greater stability for the children. In recognition of this, our government is proposing improving training for those who work with children in care to include aspects of social pedagogy.

According to the latest annual report of the Commission for Social Care Inspection, released in January, 35% of children’s homes in this country are inadequately staffed. Children’s homes in Germany are also generally larger than in the UK, catering for 22 youngsters on average, compared with six here. In Germany, most homes are run by regional authorities or on a non-profit basis by the voluntary sector. In the UK, just 6% are run by the voluntary sector, 32% by local councils, and 61% are privately owned and run for profit.

As a local-authority run home catering for nearly twice the number of children than average, Dalling Road might not be typical of most homes in this country. Nor is it typical – though more so in London and the southeast than elsewhere – in that, at the time of my visit, only two of the nine children resident were what the manager, Philip Craig, terms “citizen children”, ie, British. The rest were unaccompanied asylum seekers. “We are not a specialised asylum unit, so we are basically doing the asylum team a big favour looking after these kids,” says Craig, who hopes from this spring that the home will be used for longer-term therapeutic care of children.

But the fact that the London home cares for children for a maximum of three months is far from unusual. Compared with children’s homes in Germany, where children stay on average for nearly three years, the average length of stay in this country is less than a year. Craig and many others argue there is a desperate need for those who work in children’s homes here not to be seen simply as “firefighters” who intervene in a crisis but are not allowed to work with children for long enough to make a real difference to their lives. The extent to which children feel let down when moved from one children’s home to another, often after passing through the care of a number of foster families, is evident from the accounts of boys at another children’s home: Hillcrest Slinfold, near Horsham in West Sussex.

Hillcrest Slinfold, privately owned by a company that runs a dozen children’s homes around the country, caters for up to 20 boys aged 11 to 16. But at the time of my visit, there are 16 boys living in three separate houses on the site, which includes its own school. “In some ways this is the last of the last resorts,” says Tony Ross-Gower, manager of the home for the past two years. “Many of the boys sent here by local authorities have been deemed ‘unfosterable’ and unmanageable by other children’s homes. It is not unusual for them to have been placed in several dozen other care settings before coming here. But once here I fight hard for them to stay as long as possible.” Because of the on-site school, Ross-Gower says he is often successful in keeping boys until they have finished their education. This means the average length of stay is three years – similar to the national average in Germany.

The sense of security this gives the boys at the home is palpable. Ross-Gower says most of them have been subjected to severe abuse or neglect. “Some have lived on the street; others are persistent young offenders. Most are perceived by a certain sector of society as a complete menace who should be locked up, or at least be kept out of sight and out of mind.”

The boys are fully aware of this. Jay, 14, says: “People looked at me like I was some sort of gangster. But my old man used to beat me up and I was always getting into trouble with the police for drink and drugs. ”

In just one year before being sent to Hillcrest Slinfold, Jay, whose younger brother and sister are also “looked after”, had been placed with, and moved on by, four foster families and four children’s homes. “I couldn’t get on with foster families. It’s like they were trying to behave like my parents when they weren’t. So I kept running away. But the amount they moved me around after that felt like they were taking the piss. I couldn’t settle anywhere,” says the softly spoken teenager, who one day wants to work for the RSPCA. “Then I came here and it felt like the staff really cared. If you try to run away, they come looking for you. It’s like they want you to stay here and do well. When you know you can stay somewhere, you begin to think ahead.”

Thinking ahead is what worries David, 16, who has been in care since he was a baby and came to Hillcrest Slinfold 31/2 years ago after living with a succession of foster families and in other children’s homes. “I was assaulted by staff in some of the other homes, so I kept absconding and getting into car theft and burglary. Then I came here and began to sort my behaviour out. But I have to leave in June when I’ll be given my own flat. If I can’t cope, I guess I’ll end up in prison.”

Curtis, 15, was moved more than 30 times between foster families and children’s homes before coming to Hillcrest Slinfold a year ago. He feels the ordered regime of the West Sussex home has helped turn his life around. “All those other places were very chaotic. But here I go to class and now I’ve begun to think maybe I can follow my dream to become a mechanic.” That is if he’s given the chance. “If you say you’re in a children’s home, people put their hands in their pockets to protect their stuff. They think we’re all troublemakers who should be put away. They haven’t been through what we’ve been through. Nobody wants to hear your side of the story.”

“There is something deep in our culture that leads to a belief that we should be punitive towards children who are difficult,” says David Jones of the International Federation of Social Workers. Many believe this notion came from the industrial revolution, when so many children were set to work and residential care evolved from the Poor Law workhouses and draconian reform schools for those who misbehaved. Add to this history the recent trend for selling off school playing fields and closing down recreation facilities for children to save money – even the way education is now assessed using business terms such as performance leagues and value-added indicators – and it is not hard to see why some, such as Wiedermann, say our way of placing the care of children in the marketplace is “loveless and cold”.

Brief snapshots of life at SME compared with that at Dalling Road and Hillcrest Slinfold – the lunchtime routine – are telling in this respect. In the Hamburg home, lunch is prepared by whichever staff member was responsible for waking the children that morning. Children and staff sit down to eat together and nobody touches their plates until everyone is seated. The youngest and shyest boys are given regular hugs and encouraged by their carers to join the discussion around the table. At Slinfold Hillcrest, lunch is also cooked by the care workers on duty and the boys sit down to eat together in small groups in the house where they live.

At Dalling Road, meals are prepared by a professional cook and children drift in and out of the dining room helping themselves to whatever they want. At the lunch I visit, most staff are upstairs seated around a table for a meeting, “project-managing” the future for the children at the Hammersmith home, whom they sometimes refer to as their “client group”. When I ask to speak to one of the home’s “citizen children”, I am told he has gone missing. The staff will then follow procedure: if they have not tracked him down by phone by the end of the day, a missing- person report will be filed with the police.

“Sometimes we lose sight of the child,” says Philip Craig. Judge for yourselves.

Some names have been changed to protect identities