All posts by mcadmin

East Germany: The irony curtain

December 4, 2004

December 4, 2004

Investigation

When the wall came down 15 years ago, East Germans were promised their lives would be enriched with new homes, money and jobs flowing in from free Europe. Instead a new, invisible wall of hopelessness has been erected — and millions have moved west, leaving semi-derelict ghost towns and growing hostility. Special investigation by Christine Toomey

The illuminated hands of a vast clock sweep relentlessly above the deserted Packhof quarter of Wittenberge; the span of the dial, over 20ft across, makes it the largest clock in continental Europe. That such a giant timepiece should dominate this small town on the banks of the Elbe river seems almost like a taunt; a larger-than-life reminder that, as far as many are concerned, time is running out for Wittenberge.

For this once booming town in the former Democratic Republic of Germany now has a more dubious claim to fame. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall 15 years ago and subsequent reunification of East and West Germany, Wittenberge has seen the most dramatic exodus of people of any place in the former communist half of the country. Contrary to the “blooming landscape” the former chancellor Helmut Kohl predicted East Germany would become, when he basked in the collective euphoria of 83m Germans celebrating turning into one nation again, all that flourishes among this town’s many crumbling buildings are weeds.

Streets stand deserted. Nearly a third of the population — more than 10,000 people — have left. In the former DDR as a whole, nearly 3m — 17% of the population — have moved out, leaving well over a million apartments empty. Most have gone seeking work to the west of what was known as the “anti-fascist protection barrier” — the border that once split the country in two.

Wittenberge’s famous clock tower looms 100ft above what remains of a sprawling disused sewing-machine plant, once the town’s main employer. Alongside it sit the abandoned hulks of an oil-seed mill and textile factory. In recent years the brick facade of the mill has served as a backdrop for a small annual opera festival; an attempt by the town to breathe life into this abandoned part of town for a few days each year. The only other flurry of activity the Packhof quarter sees from time to time is the arrival of film crews shooting post-second-world-war dramas. There’s no need to build a set: the partially derelict, deserted streets offer the perfect location.

The one, hugely expensive, modernisation project completed here last summer, amid great fanfares, was a £52m upgrade of the railway station. But even this was blown a big raspberry by many residents, who viewed the upgrade, mainly of tracks, as a means for trains to thunder through the town even faster. Only once, early in the morning, does a gleaming Berlin-Hamburg express stop here for two minutes. On the rare occasions it stops a little longer, observed Der Spiegel, one of Germany’s leading news magazines, it is so that the driver can hop out “to piss on the floor of this small town before leaving the place once more forgotten by the west”.

When Chancellor Gerhard Schröder arrived to crack open a bottle of champagne to inaugurate the new station, he was greeted by a crowd of hecklers. The protest was just one sign of how deeply disenchanted many east Germans, “Ossies”, are with their west German, “Wessie”, neighbours and vice versa.

The days when millions of East Germans streamed across the newly opened border to be embraced and offered flowers by those in the west seem long past. The moment when ordinary Germans, eastern and western, stood, arms linked, singing “We are one people” is long forgotten. According to one recent opinion poll, 12% of east Germans think it would be a good thing if the Berlin Wall were re-erected; twice as many west Germans think the same. So why has the dream of a reunited Germany turned so sour?

Some have likened what has happened to a once friendly “company takeover” of the east by the west that has turned hostile. Certainly those in the west resent having poured over £1,000 billion into what has become an economic black hole; while those in the east are disillusioned that this investment, much of it in infrastructure, has failed to prevent huge job losses. But the truth lies deeper than economics. It has its roots in a split in the German psyche — a fundamental difference in mentality that exists between those living on either side of the former border, once so brutally enforced by the DDR that over 1,000 of its citizens were killed trying to cross it.

Heinrich August Winkler, one of Germany’s leading historians, describes it as a “mix of economic weakness and long-term disposition”, with its roots in the country’s authoritarian past. “As West Germany was liberated by the western allies and not the Soviet Union, it had a chance to open itself to the political culture of the West. The real tragedy for East Germany was that one form of dictatorship [Nazism] was exchanged for another, which had a tremendous psychological impact. It has taken West Germans time to realise this is a united country but still two societies.”

In the heady first years after reunification, there was talk of the “wall inside people’s heads”, expected to last well after the watchtowers and concrete barricades were torn down; 15 years on it seems, for many, this mental wall has grown. To find out why, there could hardly be a more poignant place to start looking than Wittenberge, and from there trace the stories of those along a section of where the border once followed the Elbe river — across which East and West German soldiers once regularly exchanged fire.

The headline of the newspaper cutting framed on Detlef Benecke’s office wall declares him to be “the luckiest man in Wittenberge”. Benecke runs a removals company and business is brisk. The stocky 42-year-old is a born entrepreneur. Even under the old communist regime, he launched a series of lucrative black-market schemes, including reproducing pop posters as a boy and learning how to blow glass, rolling out dozens of orders a week for family and friends.

When the wall came down, Benecke started a business repairing umbrellas. But as one factory after another closed in Wittenberge, and the mass exodus from the town began, he saw a new opening in the market — he invested first in one removals van and now has a fleet. Discussing the fate of the town where he was born, he switches off his phone and becomes earnest.

“When the factories closed, everything went to the dogs. Those in the west just decided the east would become a region of consumers, not a place where anything was made any more. Little thought was given to what the future would look like here after that. So, first, the men left to find work. Then they took their wives and children. Most of those left are either old or very young or have nowhere else to go. This place is turning into a ‘pair of dead trousers’ [a ghost town].”

One of the reasons the east’s economy was gutted so quickly was Kohl’s decision to exchange old East German ostmarks for deutschmarks on a one-to-one basis. While populist and politically shrewd, this was largely aimed at stemming a potentially disastrous flood of people moving to the west. And in the short term, it did boost the east’s economy by giving those with limited savings some spending power. But in the longer term, it wrecked any chance many East German industries had of remaining competitive; overnight, the wage costs of a much less efficient workforce were hugely inflated, virtually quadrupling the cost of their products.

Winkler, a professor at Berlin’s Humboldt University and author of a recent two-volume history of Germany, accuses west German politicians of “lacking imagination”. The assumption was that the east would soon be pulled into line with the west. Some talked of a “second economic miracle”. Much was made of the “confident, powerful” nation a united Germany would become. Some boasted: “Germany will be unstoppable”. That is not how things now look from Wittenberge.

Benecke, who has become a city councillor to try to shake up the local political status quo, blames a lack of innovative thinking among those in power. The same “old sacks”, he says, have dominated Germany’s political landscape for too long. The bureaucracy, hidden taxes and social-security payments burdening German employers are so onerous, they stifle new enterprise. Instead of stimulating the creation of new jobs by stripping away the red tape, the country has artificially propped up certain industries and manufacturers and continued with a lavish welfare system that the country’s ageing population can no longer afford.

Decades after West Germany’s economic miracle dragged the country from the rubble of war to the height of economic power, books have started appearing with titles such as Germany: The Decline of a Superstar. With unemployment at its highest in recent history, and growth stagnant, the country is experiencing what some are calling a “gloom boom”. West Germans blame it on reunification. But economists argue that the decline would have set in anyway, as Germany had evolved one of the most rigid and expensive labour markets in the world. Reunification, they argue, actually concealed the problem for years as the country went on a huge borrowing spree to pour money into the east, leaving a national debt that has breached euro-zone guidelines each year since the launch of the single currency.

In recent years, Schršder has begun the painful process of reform, causing controversy by cutting cherished social programmes. One fallout is that extremist politicians, both on the left and right, have been voted onto local councils. But from January 2005 these cutbacks will begin to bite even deeper, as unemployment benefits will be slashed from two-thirds of previous salary to a fixed welfare payment of under £100 a week. With the official unemployment rate in the east running at around 18% (unofficially the rate is closer to 40-50% in some places), compared with just over 8% in the west, this will lead to much greater hardship for those in the former DDR.

Rudiger Overlach is bent low over a small artificial pond, absorbed in creating a miniature Japanese landscape in the garden of his modest home on the outskirts of Wittenberge, as his wife starts talking about how she believes he will fare once the new reforms take effect. “From January my husband will receive €340 (£235) a month,” says Daniella, 48, who has an advanced terminal illness. “Once I’m gone, Rudi is planning on starting his own business designing Japanese gardens.” From the look of the wilted rushes surrounding the pond her 53-year-old husband is tending, this could be an uphill struggle.

“Life was good for us before. I worked in a bakery. Rudi was a builder. We raised a few pigs on the side and made enough money to build our own house. Our life was secure. When the wall fell, we thought life could only get better. But the small man has been forgotten. Our lives have become very hard. We feel used.”

Not that the Overlachs were great lovers of the old system. When he was a teenager, Rudiger escaped to the West by swimming across the Elbe. Incredibly, he swam back, undetected, a few days later after feeling guilty about leaving his ailing mother. Loose talk about what he had done led to him being jailed for two years. When Daniella applied for a passport to leave the DDR, it was denied. She became one of millions subject to surveillance by the Stasi, the secret police, among whose bizarre methods was the compilation of a “smell database” comprising stolen items of clothing such as socks and underpants, to help sniffer dogs track supposed subversives.

“We wanted freedom and now we have it,” says Rudiger, finally slumping in a chair in the garden. “But what good is it doing us? There is no work. Our young people are leaving. Our police state has collapsed, but what we have been offered in its place is an ‘elbow society’ where everyone is just out for themselves.”

As hard as it was for them, the Overlachs encouraged their only son to leave Wittenberge to find work in the west. Before I meet him at the end of my trip, when the deep divisions that still exist between those living on either side of the former border become startlingly clear, a series of encounters serve as painful reminders of how brutally divided physically Germany once was.

One road out of Wittenberge winds through a small village, little more than a street lined with old farmhouses, where 75-year-old Inge Lemme lives. One wall in her home is lined with photographs of a handsome, smiling young man with unruly blond hair; the last photograph taken when he was 21, just a few months before he was killed. This is Hans Georg, Inge’s son.

The last time Inge saw her son, he was waving at her as he cycled away from their farm after paying a short visit home during his period of compulsory military service with the East German army. It was a sunny Sunday afternoon, August 1974. Later that day, Hans Georg was due at a nearby military base, before being posted as a guard to a high-security camp for political prisoners in the north of the country. When he failed to report for duty, soldiers were sent to question Inge and her late husband. They genuinely had no idea where he was. “He wanted to protect us,” says Inge, absently stroking a photograph of her son. “Only later did we discover he had admitted in a letter to his uncle that he did not know how he was going to get through his military service.”

Inge believes the prospect of being posted to guard political prisoners, and the cruel conditions her son was expecting to have to enforce there, pushed him to attempt to escape. He was a strong swimmer, a lifeguard. He thought he could make it across the Elbe. But as soon as he was reported missing, border guards ordered floodlights to be trained on the stretch of the river nearest to his home. He didn’t attempt to cross that night. The next night, the floodlights were still on, but he felt desperate enough to attempt his escape.

The details of what happened next only emerged after the Berlin Wall fell and records of border fatalities were scrutinised by authorities seeking prosecutions of both politicians and military officers considered responsible for the shoot-to-kill policy enforced along the border.

Hans Georg, it was recorded, almost made it to the western bank of the Elbe before being seen by an East German patrol boat that had been ploughing back and forth looking for him.

When the boat drew level with him and tried to pull him on board, according to one crew member, he dived below the surface, shouting: “It’s now or never.” The captain of the boat then systematically raked his craft backwards and forwards at speed until he felt the propeller meet resistance, then announced with satisfaction: “That’s got him.” The propeller had sliced through Hans Georg’s skull. His body was left to rot in the water for three weeks in the hope that this would disguise the exact cause of his death.

When his body was returned to his family, his parents were told they were to blame for “bringing him up improperly” and “filling his head with false ideas”. The family had relations in West Germany with whom they exchanged limited correspondence. Six years ago an attempt was made to prosecute the captain of the boat for manslaughter. But his crew mates suffered a sudden bout of amnesia, claiming they could not recall what had happened, and he was acquitted.

“I paid the highest price possible because of the wall,” Inge says. “I understand how desperate a lot of people feel because they have no work. It is not an easy situation. But I cannot understand anyone who says they want the wall back.”

Further along the river, in the hamlet of Vockfey, Hans Ebeling, an elderly farmer with a smallholding that had once sat precariously close to the electrified fence following the line of the Elbe, recalls sometimes hearing gunshots fired at those trying to cross the border. “We never thought contact with the west would come so rapidly. The sudden freedom was both beautiful and unexpected,” says Ebeling, who became a local councillor when the wall fell, and fought hard for the community of Neuhaus, within which Vockfey sits, to be incorporated back into the west German region of Lower Saxony, to which it traditionally belonged. This has brought the area some financial benefits. But it still lags far behind the prosperous Lüneburg across the river and, further afield, Hamburg, one of the wealthiest cities in Europe. “Young people today have no idea how it was back then,” says Ebeling. “They look back and think things were better.”

You do not have to search far to understand what he means. The young in nearby Neuhaus are unanimous in their belief that their only hope of a job lies across the river in affluent Lüneburg. And yet they express a strong sense of nostalgia — or “Ostalgie”, as the Germans have dubbed it — for the East German way of life their parents knew.

Drawing a veil over the fact that it was a society more spied on than any other in history, they, like many others, talk of the former DDR as a cosy, communal Heimat (homeland). Such sentiments have made the recent German film Good Bye Lenin! a hit, and meant former food staples such as Bulgarian plums, ersatz coffee — made from charred vegetables — and the old-fashioned Trabant cars that families waited years to acquire are now undergoing a revival.

Without meaning it as a metaphor, Iris Goigal, a 17-year-old pupil at Neuhaus’s high school, says: “At least you knew where you were when the wall was there.” She means it literally, explaining that her mother used to get lost in East Berlin and could only orient herself by looking at the wall. But it is as if not only her mother’s generation but hers too now feels so lost, they can only find their bearings by referring to the psychological barrier that still separates east and west.

Little remains today of the real Berlin Wall. Most of it was ground to rubble and used as the foundation for a network of new autobahns across east Germany. Potsdamer Platz, once a no-man’s-land across which concrete barriers and barbed wire stretched, now has a McDonald’s and Starbucks. When an artist recently re-created a portion of the wall in the capital near the former Checkpoint Charlie, erecting 1,065 wooden crosses in memory of those who lost their lives trying to cross the border, it caused an outcry. The installation was condemned as a “Disneyfication” of the cold war. But many saw the row as a sign that those in the west would prefer to forget the country’s troubled past.

Sitting in a classroom discussing their hopes for the future, Iris and other pupils in Neuhaus constantly repeat the message they receive from their parents: that life was more secure before the wall fell. A job, at least, was guaranteed, health care was free and the education system better. Only one boy, Denny Lengkeit, dares to say: “We wouldn’t want the wall back, or the spies or the border guards.” But, with the brashness of youth, he voices the belief, widely held but rarely expressed so openly that: “Even so, there was a lot about the old system that was good.” At this the girls in the group talk enthusiastically about the “community spirit” their parents once enjoyed and they crave. There is little doubt that under the extreme conditions of a totalitarian state, neighbours and friends (ones not signed up by the Stasi, that is) had to support each other more to devise ways of loosening society’s straitjacket.

On the outskirts of Lüneburg, in the driveway of the smart house that Daniella and Rudiger Overlach’s 29-year-old son, Silvio, has built for his family, a new Mercedes CLK 200 sits as a gleaming symbol of newly acquired wealth. While the car is mainly used for driving back to Wittenberge to visit his father and ailing mother, it is clear that, in material terms, moving to Lüneburg has enabled Silvio, his wife, Kathrin, their young son and baby daughter, to achieve a comfortable lifestyle. Not that it wasn’t hard won. When Silvio first moved west he says he encountered the sort of discrimination many East Germans complain about. Employed by a construction company for almost half the wage paid to his West German counterpart, he and the other Ossies were given accommodation in a removals container. “We were considered cheap labour, so naive and desperate for work that we would take whatever we were given.”

When his wife joined him and started work as a book-keeper, they were able to rent a small flat. Silvio then started an internet company selling ornamental swords and daggers, which grew out of his passion for the martial arts. To his surprise the company quickly took off, enabling the family to buy a plot of land and start building their own home. But this led to further trouble.

Their elderly neighbours appeared to take an instant dislike to them, eventually complaining to the police that Silvio had exposed himself in the garden, a complaint that the police found groundless. Silvio believes at its root was a feeling of resentment many Wessies feel for their Ossie neighbours. “People here seem to simply look for reasons to pick a fight,” he laments.

In the comfortable setting of Lüneburg town hall, Ulrich Medge, the mayor, tries to explain what he believes lies at the root of such antipathy. “In the beginning, those from the east were welcomed with open arms. But when the euphoria subsided and reality set in, west Germans realised east Germans would be competing with them for jobs, and then there was this huge outflow of money from their pockets to try and shore up the former DDR. When all they heard in return were complaints from those in the east about how hard their lives had been, things began to wear thin. From the west German perspective there is a feeling that we struggled for 40 years to pull this country out of the ashes of war and yet those in the east expect their lives to be transformed overnight.”

Medge is too diplomatic to admit that basic prejudices arising from different mindsets also run just below the surface. While Ossies see themselves as more open- and social-minded than those in the west, Wessies view them as whiny and slow-thinking. And while Wessies see themselves as modern, sophisticated and experienced in the ways of western capitalism, they are viewed in the east as arrogant and making Ossies feel like second-class citizens.

As far as Medge and most Germans are concerned, it will take another generation, maybe two, before the tensions between east and west ease and the mental wall that continues to exist in many people’s minds finally crumbles. But right now, for Silvio Overlach, the differences are simply too great. He has recently decided to try and move back to Wittenberge. His expanding business, he feels, can be conducted just as well from there — if not better. “Workers in the west have had it so good for so long they don’t put much effort in and, I have found, are unreliable,” says Silvio. “I’d rather employ someone from the east any day. I know they’ll show up for work. They need the money.” There is some documentary evidence to support this: one recent banking report noted that east German workers, on average, clock up 100 hours more per year than their western counterparts.

“As far as I’m concerned it is east Germany, not west, that is the land of opportunity,” Silvio concludes. “Just like in America, when the pioneers started moving out to the Wild West.”

Few exemplify this “pioneer” spirit better than Detlef Benecke; even if, in his case, it has a rather macabre edge. Once Benecke has helped all those who want to leave Wittenberge, I inquire, what direction does he see his business taking? Without missing a beat, he replies that he has been thinking about opening a funeral transportation service, maybe a crematorium.

“It looks like only the old will be left here soon,” he says. “They will need catering for eventually.” But if others like Silvio Overlach start moving back, bringing new business opportunities with them, there may be hope for Wittenberge yet. The future of the east, says the historian Winkler, depends on a “renaissance of civil society”. And already, he says, there are “positive symptoms”.

On my way out of Wittenberge, I glance up at the giant clock and note it is running 15 minutes fast. Rather than time running out for places like this, optimists like Silvio would argue they could, eventually, find themselves ahead in the race to galvanise Germany and rid it of its reputation as the sick man of Europe. But at the moment, in east Germany, optimists are in short supply.

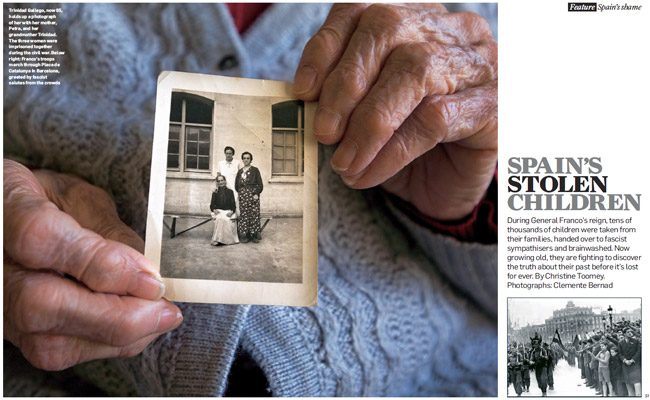

Spain’s stolen children

March 1, 2009

March 1, 2009

Investigation

During General Franco’s reign, tens of thousands of children were taken from their families, handed over to fascist sympathisers and brainwashed. Now growing old, they are fighting to discover the truth about their past before it’s lost for ever. By Christine Toomey. Photographs: Clemente Bernad

The only memory that Antonia Radas has of her father has haunted her as a recurring nightmare for nearly 70 years; it is the moment of his death.

Antonia is a small child in her mother Carmen’s arms. Both are looking out through the refectory window of a prison where Carmen’s husband, Antonio, is being held. They see him lined up against a courtyard wall. Shots ring out. Antonia sees a red stain burst through her father’s white shirt. His arms are in the air. Another bullet goes straight through his hand.

After that Antonia believes she and her mother must have fled the prison. But Carmen and her two-year-old daughter were soon arrested. They had been arrested before. That was why Antonio had given himself up, thinking this would guarantee their freedom. But they were the family of a rojo or red — a left-wing supporter of Spain’s democratically elected Second Republic, crushed by General Francisco Franco’s nationalist forces during the country’s barbarous 1936-to-1939 civil war. As such they would be punished. These were the years just after the war had finished, and the generalissimo’s violent reprisals against the vanquished republicans were in full flow.

Antonia is now 71 and living in Malaga. Her memories of much of the rest of her childhood are clear, and many of them happy. “I was raised like a princess. I was given pretty dresses and dolls, a good education, piano lessons,” she says.

It is only when I ask what she remembers about her mother, Carmen, from her childhood that Antonia’s memory once again becomes sketchy. “I remember that she was thin and she wore a white dress. Nothing else. I didn’t want to remember anything about her,” she says with a steely look. “I thought she had abandoned me.”

This is what the couple who raised Antonia told her when she came home from school one day when she was seven years old, crying because another child had said that she couldn’t be the couple’s real daughter since she did not share their surnames. “They told me that my mother had given me away and that my real family were all dead. They said they loved me like a daughter and not to ask any more questions. So I didn’t.”

By then a culture of silence and secrecy had descended on the whole of the country, not just the south where Antonia grew up. These were the early years of Franco’s dictatorship, when loose talk, false allegations, petty grievances and grudges between neighbours and within families often fuelled the blood-letting that continued long after the civil war had finished. In addition to the estimated 500,000 men, women and children who died during the civil war — a curtain-raiser for the global war between fascism and communism that followed — a further 60,000 to 100,000 republicans were estimated to have been killed or died in prison in the post-war period.

Even after Franco’s death in 1975, after nearly 40 years of fascist dictatorship, few questions were asked about the events that had blighted Spain for nearly half a century. To expedite the country’s transition to democracy, the truth was simply swept under the carpet.

Franco’s followers received a promise that nobody would be pursued, or even reminded, of abuses committed. In 1977, an amnesty law was passed ensuring nobody from either side of the bloody conflict would be tried or otherwise held to account. A tacit agreement among Spaniards not to dwell on the past took the form of an unwritten pacto de olvido — or pact of forgetting, which most adhered to until very recently, when the mass graves of Franco’s victims began to be unearthed.

While the majority of his nationalist supporters had long since been afforded decent burials, the bodies of tens of thousands of republicans — many subjected to summary executions — were known to be buried in unmarked pits.

In 2000, a number of relatives’ associations sprang up to try and locate the remains of missing loved ones. When the socialist prime minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero was elected in 2004, the agreement not to rake over the past was ruptured; during his election campaign he made much political capital out of the country’s left-right divide by repeatedly reminding voters that his grandfather had been a captain in the republican army and had been executed by Franco’s military.

To mark the 70th anniversary of Franco’s coup, Zapatero, in 2006, drafted a controversial “historical memory” law intended to make it easier to find and dig up the mass graves of republicans by opening up previously closed archives. In addition, the law — a watered-down version of which was passed after much heated political debate — ordered the removal of Francoist plaques and statues from public places. It also set up a committee to which former exiles, political prisoners and relatives of victims could apply to have prison sentences and death penalties meted out by the Franco regime declared “unjust” — not illegal, given the huge financial implications for the state in terms of compensation this could entail.

Since then, however, such issues surrounding atrocities committed by Franco’s henchmen have become bogged down in a legal quagmire.

Attempts last autumn by one of the country’s leading judges, Baltasar Garzon, to have Spanish courts investigate, as human-rights crimes, the cases of more than 100,000 “forced disappearances” under the Franco regime came up against a judicial brick wall when the country’s high court ruled it had no jurisdiction over such matters, given the 1977 amnesty law. While legal experts continue to argue over whether such crimes recognised by international law are subject to statutes of limitations, regional courts have been asked to gather information about those who disappeared — most of them killed — within their territory.

It is amid this current legal wrangling that one of the least-known chapters of Spain’s sad history has emerged — and it is not about the dead but the living. It concerns those like Antonia, who have come to be known as “the lost children of Franco”.

Both during the war and the early years of Franco’s dictatorship, it is now estimated that between 30,000 and 40,000 children were taken from their mothers — many of whom were jailed as republican sympathisers — and either handed to orphanages or to couples supportive of the fascist regime, with the intention of wiping out any traces of their real identity. Often their names were changed, and they were indoctrinated with such right-wing ideology and religious dogma that, should they ever be found by their families, they would remain permanently alienated from them psychologically.

While similar policies of systematically stealing children from their families and indoctrinating them with lies and propaganda are known to have been carried out by military regimes in Latin American countries, such as Argentina, Guatemala and El Salvador, in these countries trials and truth commissions have long since sought to expose and punish those responsible. But in Spain, the process of uncovering what happened to these children — like that of unearthing mass graves — is only now stirring intense and painful debate.

This is partly because the events happened much longer ago, making them more difficult to unravel. But also because the country’s tense political climate has turned what has become known as “the recovery of historical memory” into such a contentious issue that many argue it should be dropped from the public sphere altogether and remain a purely private or academic matter.

Where this would leave the “lost children of Franco” is unclear. Just how many are still alive and looking for their families is uncertain. But given their advancing years, at the beginning of January Garzon sent an additional petition to regional Spanish courts arguing that, as a matter of urgency, they should offer help to such “children” — now pensioners like Antonia — and families wanting to uncover the truth about the past before all traces of their origins are lost.

Garzon is requesting that DNA samples be taken from those searching for lost relatives — such genetic databases have long existed, for instance, in Argentina — and believes the cases of the “lost children” should also be treated as forced disappearances, ie, human-rights crimes without any statute of limitations. The DNA would be taken from those who are looking for missing relatives and matched with samples taken from those who believe their identity may have been changed when they were a child.

In many ways Antonia considers herself lucky. More than 50 years after she was separated from her mother in prison, the two were finally reunited, briefly — Carmen died 18 months later. Yet despite the apparent happy ending to her story, Antonia displays such deeply ambivalent feelings about her mother as we talk that it is clear that Franco’s aim of psychologically alienating the children of “reds” from their families was achieved. Even now Antonia does not like to be reminded of the name her mother gave her when she was born — Pasionaria, in honour of the civil war communist leader Dolores Ibarruri, known as La Pasionaria. She tuts loudly when her youngest daughter, Esther, writes it in my notebook.

“I believe if she [Carmen] had really wanted to find me when I was still a child, she would have,” Antonia says bitterly, ignoring the fact that when her mother was released from prison in the mid-1940s, like other former republican prisoners, she lived a life of penury, her freedom to work, move and ask questions severely limited.

Mother and daughter were reunited in the end through the efforts of one of Carmen’s older daughters, Maria, who, together with another daughter, Dolores, and son Jose, both then in their teens, had been left to fend for themselves when Carmen was imprisoned with their baby sister. Determined that her mother should see her lost child before she die, in 1993 Maria appealed for information about her sister on a television programme dedicated to locating missing relatives, which Antonia saw, by chance.

It was only then that Antonia learnt that her mother had signed a document handing her daughter into the care of a fellow prison inmate about to be released — prison rules dictated that no child over the age of three be allowed to remain with their mothers — on condition that the girl be returned to her when Carmen herself was freed from jail. Instead, her infant daughter was given, or sold, to the couple who raised her — devout churchgoers who took her to live in Venezuela for some years when she was a teenager, which was when they finally changed her surname to match their own. Carmen had already changed her daughter’s name to Antonia when she was a young child to try and protect her from the wrath of anti-communists.

All this Carmen was able to tell her daughter in the short time they had together before she died. The couple who raised Antonia were already dead by the time of the reunion, but she seems to bear them no grudges, realising they gave her a more comfortable childhood than her siblings had. The deep rancour this still causes between Antonia and her eldest sister, Dolores, is evident, as I see the shadowy figure of Dolores stand briefly outside the window of the downstairs room where I sit talking to Antonia in a rambling house in Sarria de Ter, Catalonia, where she is visiting her daughter, grandchildren and other members of her natural family. Dolores looks in at us, glowers, then walks off, shaking her head. She does not like her sister talking to strangers about the past, and jealously guards her own family secrets. She will not tell Antonia, for instance, where their father’s body is buried — though Antonia knows she carries the details on a piece of paper in her purse — believing that only she, who suffered a life of poverty and misery during and after the civil war, has the right to place flowers on his grave.

Such complicated emotions between siblings and other relatives concerning the events of the civil war and its aftermath are mirrored in families throughout Spain. It is one reason why this period of history was so little discussed for so long. “It is astonishing how many families are from mixed political backgrounds, with maybe a husband on the left and a wife on the right, which meant such things were not discussed over Sunday lunch,” says the historian Antony Beevor, author of the definitive history of the civil war — The Battle for Spain. Beevor believes that public debate about such events is long overdue. “The pact of forgetting was a good thing at the time, but it lasted too long. When you have deep national wounds and you bandage them up, it is fine in the short term, but you have to take those bandages off fairly soon and examine things, preferably in a historical context rather than in a completely politicised one.”

Like many others, Beevor believes Garzon’s attempts to bring such matters before the courts have turned them into a political football that is now being kicked about both by the right and the left for their own ends at a time when Spain can ill afford such bitter polarisation. The country is still grappling with the aftermath of the 2004 Madrid train bombings, carried out by Islamic fundamentalists, continuing terrorist attacks by Eta, growing demands for more regional autonomy, and the fallout of the global financial crisis.

“Why try to drag all this through the courts now. Who are they going to put on trial after all this time? Ninety-year-olds who are beyond penal age?” says Gustavo de Arestegui, spokesman for the country’s conservative Popular party. “Those at the top of the hierarchy of the Franco regime are all dead. Let history be their judge.”

But such arguments miss the point, says Montserrat Armengou, a documentary-maker with Barcelona’s TV channel, who both wrote a book and made a film about Franco’s “lost children” with her colleague Ricard Belis and the historian Ricard Vinyes. “There never has been and never will be a good time to uncover the truth about this country’s past. But the longer we wait the more difficult it will become, because those who were directly affected and know what happened will have died.”

Another part of Garzon’s petition to the courts at the beginning of this year regarding Franco’s “lost children” was a plea that regional magistrates urgently order statements be taken from surviving witnesses to how children were separated from their mothers in Franco’s jails before their testimonies are lost. One such witness is Trinidad Gallego, who we meet in her small apartment in the centre of Barcelona. Aged 95, she talks lucidly, and in a booming voice, about the things she saw when imprisoned with her mother and grandmother in a series of women’s jails in Madrid after the end of the civil war.

As a nurse and midwife, Trinidad was present at the birth of many babies in prison, though few records — either of children brought into the prison or born there — were ever kept.

“I saw some terrible things in those prisons,” she says. “Mothers were kept separated from their children most of the time and all mothers knew their children would be taken away before they were three years old. The priority was to brainwash the children so they would grow up to denounce their parents.”

From the early 1940s onwards, many children of prisoners were transferred into orphanages known as “social aid” homes, said to have been modelled on children’s homes established in Nazi Germany. Their parents were not told what happened to them after that; a law was passed making it legal to change the names of the children, who, thereafter, had no legal rights. The historian Ricard Vinyes has described the orphanages as “concentration camps for kids”. Those who spent time in such places have spoken about how they were made to eat their own vomit and parade around with urine-soaked sheets wrapped around their head.

Victoriano Cerezuelo was registered simply as “child number 910 — parents unknown” when he was placed as a baby in the maternity ward of an orphanage in Zamorra at 8am on April 15, 1944 — the day recorded as his birthday, although he was already weeks or maybe months old by then. When he was five, Victoriano was adopted by a farming couple, but was returned to the orphanage seven years later when the wife, sick of being beaten by her husband, threw herself down a well. “After that I placed an advert in a local paper trying to locate my real parents. As a result, I was beaten to within an inch of my life by a priest, while a nun at the home told me “the more you stir shit, the worse it smells”, recalls Victoriano, 64, as he sits in his Madrid apartment fingering a small black-and-white photograph of himself as a boy. “I would just like to know who my parents were before I die.”

Uxenu Ablana, who spent most of his childhood being transferred from one orphanage to another in Asturias, northern Spain, knows who his parents were. His mother was tortured to death by nationalist forces to extract information about his father, who had been jailed for lending a car to republican officials during the civil war. Uxenu can still recite by heart all the fascist

Falange anthems that were drummed into him in these homes, together with so much force-fed Catholic dogma that, initially, he quibbles about meeting me when I tell him my first name is Christine, so much does he still hate religious reminders. “I have no words to describe all the pain I went through. We were domesticated like dogs, beaten and humiliated, made to wear the Falange uniform and give fascist salutes,” says Uxenu, 79, when we eventually meet in Santiago de Compostela, where he now lives.

“I am not a lost child of Franco — I am dead. They killed me, what I could have been, when I was put in those homes. They brainwashed me against my father and true Spanish society.”

When he was able to leave the orphanage at the age of 18, Uxenu, whose name had not been changed, was tracked down his father, who by then had been released from jail. But the two were strangers and quickly lost contact. “I had to keep quiet for so long about what happened to me, and I still feel like a prisoner in a society that does not want to talk about the past,” says Uxenu, whose wife is so opposed to him recalling his childhood experiences we have to meet in a restaurant.

The problems that Uxenu, Victoriano, Antonia, and who knows how many more, have faced and continue to face regarding their past as Franco’s “lost children” is justification enough in the eyes of Armengou and others for Garzon to pursue his attempt to get what happened to them classified as a crime against humanity. Fernando Magan, a lawyer for a group of associations representing Franco’s victims, vows he will take the case to the European Court of Human Rights and the United Nations if Spanish courts fail to properly address the issue. “Justice is not only about prosecuting those responsible for crimes, it is about helping victims uncover the truth about what was done to them or to their loved ones — in this case in the Franco era,” argues Magan.

To those who say it is time Spain turned the page on this period of its past, Uxenu voices what many feel: “Before you can turn a page you have to understand what was written on it. Unfortunately here in Spain, we are still at war — a war of words and feelings.”

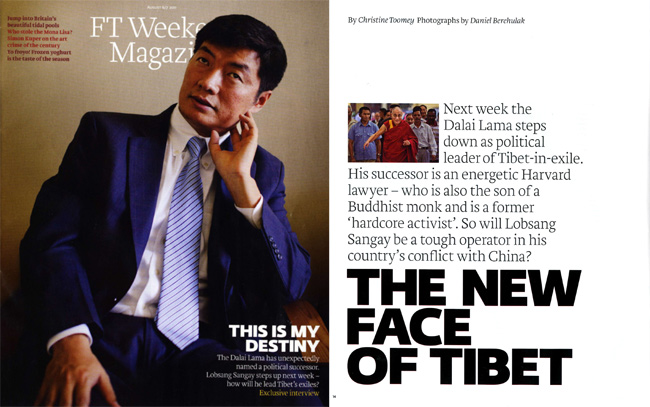

The New Face of Tibet

6th August, 2011

Next week the Dalai Lama steps down as political leader of Tibet-in-exile. His successor is an energetic Harvard lawyer who is also the son of a Buddhist monk and is a former “hardcore activist”. So will Lobsang Sangay be a tough operator in his country’s conflict with China? By Christine Toomey.

Lobsang Sangay doesn’t know the exact day on which he was born. Nor did most of the small boys and girls who turned up with him for their first day of school, clutching the hands of parents too traumatised to truly mark such things as birthdays. But were it not for the bloodshed his father had witnessed, Sangay would not have been born at all. For more than twenty years before his son’s birth in 1968 his father had been a Buddhist monk in a remote monastery in Tibet.

When it came to entering Sangay’s details in the school register his parents nominated the day of his birth as March 10th. So did the parents of a third of his classmates. To Tibetans March 10th is known as National Uprising Day, marking the height of the 1959 armed rebellion against Chinese domination of their ancient homeland.

“The story of my life as a refugee is all there in not even knowing my own birthday,” Sangay reflects with the air of a man well acquainted with hardship.

Out of the window of the small plane in which we are flying towards the North Indian hill station of Dharamshala, the snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas loom into view. None of the other passengers on the plane give Sangay a second glance. But while he may still be a complete unknown, in a matter of days he will step into the shoes of one of the most instantly recognisable figures on the planet.

On August 8th this towering, talkative and engaging 43-year-old will take over the temporal duties of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, who stunned his devotees last March when he announced that he would be retiring this summer from his role as political leader of the exiled Tibetan movement he has spearheaded for the past five decades.

The story of how this has come about unfolds as our plane follows the line of the Himalayas north. Sangay talks in painful detail of the events that forced his parents to trek across these mountains when resistance to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army proved futile. For years before this the PLA had been brutalising Tibet, especially targeting monasteries and nunneries in an attempt to break the people’s deep Buddhist faith and bring the strategically critical territory within the communist fold.

As a boy Sangay recalls his father talking of a river close to his monastery in eastern Tibet running red with the blood of slaughtered monks. It was in the face of such savagery that his father abandoned monastic orders and briefly became a resistance fighter before joining the tens of thousands of Tibetans who fled across the Himalayas into Nepal, following their spiritual leader the Dalai Lama into exile.

Thousands of exiled Tibetans endured backbreaking work as hard labourers or scraped a living from small plots of land surrounding makeshift refugee camps. Children were born in haphazard conditions. Sangay and his two younger siblings were raised close to one of these camps in Darjeeling, West Bengal, where his father had met and married his mother after she was abandoned as a teenager because she had broken a leg while fleeing across the Himalayas.

Despite such harsh origins Sangay fought his way out poverty through academic graft. When he excelled at school his parents sold one of the family’s three cows to pay for his education. After a stint at university in Delhi, he won a scholarship to Harvard Law School, remaining there as a senior research fellow, living a privileged western lifestyle, for the past fifteen years. Then his life took an extraordinary turn when the Dalai Lama made his surprise announcement on March 10th – Sangay’s 43rd “birthday”.

Sangay was in Dharamshala at the time. For months he had been campaigning for a post called the Kalon Tripa, or Prime Minister, of the Tibetan government-in-exile, a role that has traditionally been little more than an administrative post within an organisation largely subordinate to the Dalai Lama himself. Sangay had been encouraged to put himself forward by those who wanted to see a younger layperson in the role that had previously been held only by senior Buddhist priests.

In recent years Tibet has been rocked by demonstrations against the discrimination suffered by the six million Tibetans who now find themselves living within China. Two thirds of them live far beyond the borders of what the Chinese euphemistically call the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) which covers only half of what Tibetans claim as their ancient territory.

Since the violent crackdown on protestors on the streets of Llasa in 2008, human rights groups report there are now more Tibetan political prisoners in Chinese jails than at any time in recent history. According to GuChuSum, an organisation which helps former political prisoners who have escaped from Tibet, there were at least 824 named political prisoners in detention in March 2011. The whereabouts of many more is unknown.

In the face of such unrest and tensions amongst those in the 145,000 strong exile community around the world, Sangay was seen as a much-needed, dynamic, and highly qualified shot in the arm for the exile leadership. At Harvard he specialised in international human rights law and much of his energy has been devoted to bringing Tibetan and Chinese academics together.

Yet little had prepared Sangay for the Dalai Lama’s retirement announcement. For the past three hundred years, successive Dalai Lamas have fulfilled the dual role of supreme spiritual guide and political figurehead. But as the current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, has slipped further into old age, the 76-year-old has made it increasingly clear he wants to end the “culture of dependency” that has grown around him.

“As early as the 1960s, I have repeatedly stressed that Tibetans need a leader, elected freely by the Tibetan people, to whom I can devolve power. Now we have clearly reached the time to put this into effect,” he announced on March 10th. In future, he declared, political leadership will rest with whoever is elected Kalon Tripa.

When Sangay heard these words he sank into “denial mode”. “That day was the start of a real emotional roller coaster, many anxious moments and a lot of introspection,” he says. “I realised, if what His Holiness was saying went through it could be me stepping into his shoes.” Several weeks later his anxiety proved well founded. On April 26th the results of a poll conducted over several months within the exile community elected Sangay as the next Kalon Tripa.

When I ask Sangay how he now feels about taking over the temporal duties of a man regarded by his followers as a living god at a time when Tibet stands at such a critical crossroads Sangay replies that it is his “leh”, or karmic destiny.

Despite this self-effacing manner, those who know Sangay describe him as “extremely ambitious”, an unusual trait in Tibetan culture, which values humility as one of the highest virtues. Married to a descendent of one of the founding kings of Tibet, he and his wife, also born in exile, have a three-year-old daughter. He plans to move his family to Dharamsala once he takes up his new position.

Sangay tells a touching story of how hard it had been, given his impoverished background, to win the approval of his wife’s parents for her hand in marriage. “I told my wife’s father “I am nothing now and maybe I don’t deserve your daughter. But one day I’ll show you I will be someone.” Fortunately he took me at my word,” he says, a broad smile spreading across his handsome features.

As our plane touches down Sangay slips on a pair of aviator sunglasses and emerges onto the tarmac swinging his finely cut suit jacket over his towering, athletic frame – he has become an avid American baseball fan. A starker contrast to the balding, be-robed holy man whose political role he is about to assume would be harder to imagine.

While to the Chinese authorities who rule Tibet with an iron fist the Dalai Lama is “a wolf wrapped in robes, a monster with a human face and an animal’s heart”, to millions of Buddhists around the world he is the 14th reincarnation of the supreme Buddha of Compassion. Globally he is regarded as an icon for peace; in 1989 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his consistent opposition to violence in his quest for Tibetan self-rule. These are large shoes to fill.

Despite Sangay’s insistence that he will continue to support the Dalai Lama’s long-held stance for peaceful negotiations – the so-called “Middle Way” – some point to his praise for the “Jasmine Revolution” in the Arab world as an indication this could change in future. “The new leader (of Tibet) will have to take advantage of the changes in the Muslim world. When the opportunity presents itself, one must take advantage,” he said while campaigning, leading some to speculate whether Tibet could also face its equivalent of the “Arab Spring”.

Until now the moral weight the Dalai Lama has carried has kept a lid on the situation becoming more volatile. One sign of the concern many feel at the prospect of this restraining influence diminishing are the pleas, culminating in a formal petition by the government-in-exile, that he change his mind about ceding his temporal power. When the Dalai Lama refused, he was asked to consider continuing as a “ceremonial head of state” with a constitutional role similar to that of the British monarchy. “If you give me a queen, maybe I will reconsider,” the aging monk quipped before firmly declining the request.

While his supporters laud the Dalai Lama’s decision to democratise his people’s leadership, at a time when autocrats around the world are brutally clinging onto power, a few outspoken critics believe now is not the time for him to go. “I see nothing wonderful in a shepherd abandoning his flock mid-way through the desert,” says Llasang Tsering, a former president of the Tibetan Youth Congress, who refers to himself as “the resident devil” of Dharamshala because he dares voice a different view from the Dalai Lama’s.

Tsering believes it is time for Tibetans to admit that the Middle Way has not worked and change to more confrontational tactics. “China has no need to negotiate with a bunch of poor refugees,” he argues. “People are dying for true freedom in Tibet and they need international support. They need it now before it is too late. Tibet is not just about the fate of 6 million people it is about control of the roof of the world, an area two-thirds the size of Europe with vast mineral reserves, where all the major rivers of Asia have their source and where China has untold numbers of strategic missile bases.” From the point of view of Beijing, which has just celebrated its 60th anniversary of “the peaceful liberation of Tibet”, China brought “democracy” to a benighted and backward nation of serfs, while today providing the region with modernity and development through huge amounts of investment.

But given China’s economic clout and the fact that Beijing threatens ill-defined consequences for any country that agrees to formal contact with the Dalai Lama, a sudden wave of official support for Tibet by the international community seems a forlorn hope. Despite being feted as a man of peace, not least by adoring Hollywood stars, most of the Dalai Lama’s contact with foreign leaders is in an informal capacity as a religious figurehead. This spiritual back door will not be open to Sangay.

In addition to battling international indifference Sangay will also have to contend with increasing tensions between older and younger Tibetans. Growing numbers of the younger generation – increasingly frustrated, tech-savvy and radical – now support full independence. “Tibetan youngsters are increasingly educated and aware of their rights. They are fed up of Tibetans being depicted as some kind of exotic tribe,” says Tenzin Tsundue, a Tibetan writer and freedom activist.

Within Tibet the young are resorting to desperate measures. On March 16th a 20-year-old monk at Kirti monastery in the far north set himself alight, later dying of his injuries, in protest at growing Chinese repression. This led to 300 monks from this one institution alone being arrested and taken to an unknown location. “According to our Buddhist faith we should cause neither others nor ourselves harm, so suicide is considered gravely wrong. But the situation in Tibet is now so critical people are feeling desperate,” says Kanyag Tsering a senior monk at an affiliated monastery in Dharamshala.

The treatment those arrested can expect is graphically illustrated by one former nun who escaped from Tibet via Nepal in 2004. She is still so traumatised she requests to meet on a remote hillside in Dharamshala where no-one can overhear us. After being arrested when she was 16, Nyima, now 32, describes how she was tortured in prison for five years. In summer she was forced to stand all day outside on a box with sheets of newspaper stuck under her armpits and between her legs – if the newspapers slipped she was savagely beaten. In winter she had to stand barefoot on blocks of ice until her skin peeled away from the bone. When she substituted the words of a song in praise of Chairman Mao for her own version paying tribute to the Dalai Lama she was locked in solitary confinement for twenty one months. “I want people to know what is happening inside Tibet. If people know this how can they not help,” she says in a voice barely louder than a whisper. “It’s true we need urgent help. Time is running out. Very soon Tibet will be nothing more than a giant museum, our culture will effectively be dead,” concludes Kanyag Tsering.

Despite such desperation Sangay insists he will stick to pacifist principles in tackling the leadership challenge he now faces. “Look what Gandhi achieved with his non-violent movement! I do believe eventually Tibet can succeed too. If it does, this will be the most beautiful story of the twenty first century,” he says throwing his arms in the air as if in supplication. Shifting geo-politics, he argues, will eventually lead to a break-through in the impasse in Chinese-Tibetan relations.

It is a cautious and conciliatory argument. But Sangay gives the impression of a man who plays his cards close to his chest. He is clearly a shrewd operator. In a culture that frowns on self-promotion he delights in describing how he campaigned for the post of Kalon Tripa by “not campaigning”, instead touring refugee communities throughout India giving lectures so that his face was more instantly recognisable than his rivals at the polls.

In his youth Sangay admits he was a “hard-core activist”, his early student days frequently interrupted by short spells in jail for protesting in favour of Tibetan independence. He claims he has mellowed with age, quoting Churchill’s adage that if you’re not liberal when you are young you have no heart and if you’re are not conservative by 40 you have no head.

The only flicker of what Sangay really feels about the Chinese regime comes in an anecdote about how he requested permission to travel to Llasa several years ago – like most exiles below the age of 50 he has never set foot inside Tibet. Following the death of his father, he wanted to travel to the Tibetan capital to light a traditional butter lamp in his memory. He was refused. “That was very painful,” says Sangay. “I realised then what sort of people I was dealing with.”

Sangay does go on to admit, however, that if the stalemate in negotiations with the Chinese continues “and the people want me to change policy I will.” “That doesn’t mean I’m advocating official policy should change. But wherever there is repression there is resistance,” he concludes, drawing on another well-worn quote – this time from Tibet’s former nemesis Mao Zedong.

Given this possibility that the Dalai Lama’s political successor could adopt a much tougher position in future the question of who will one day take over as Tibet’s spiritual leader becomes ever more pressing. Few doubt Beijing will attempt to install its own handpicked spiritual successor. Flying in the face of centuries of tradition, during which successive Dalai Lamas have been recognised through a mysterious process of prayer and divination, the officially atheist Chinese government saw no irony in announcing in 2007 that it alone has the right to determine who will succeed Tenzin Gyatso.

Meanwhile the Dalai Lama himself is said to be considering alternative scenarios for his spiritual succession. According to his nephew and official spokesman, Tenzin Takhla, his uncle will be convening the latest of several meetings of senior lamas to discuss this in Dharamshala in September. “Right now there is no urgency and most Tibetans don’t even want to think about it. The important thing now is to let everything surrounding the change in political leadership settle down,” says Takhla, seated in a sunlit antechamber of the Dalai Lama’s private residence. “But this is something that His Holiness has been thinking about for some time.”

* * * * *

Twenty kilometres along a deeply rutted road from Dharamshala, one possible successor to the Dalai Lama sits under virtual house arrest. Ever since his dramatic escape from Tibet in January 2000 at the age of fourteen, after days of treacherous driving through mountain passes, trekking around checkpoints and a spell on horseback, Ogyen Trinley Dorje has been treated with deep suspicion by the Indian authorities. Security agents are permanently posted outside his private quarters at the Gyuto monastery in Sidhbara.

As head of the Karma Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, Dorje is one of two claimants to the title of the 17th Karmapa, a reincarnation of Buddha pre-dating that of the Dalai Lama by more than two hundred years. After the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama – the second highest-ranking lama of the Gelug order – the Karmapa is widely regarded as third in line in the Tibetan spiritual hierarchy, in as much as such an esoteric order exists.

The position of Karmapa took on greater significance, however, after the mysterious disappearance in Tibet of five-year-old Gendun Choekyi Nyima, identified by the Dalai Lama through traditional divination as the 11th Panchen Lama in 1995. Shortly after his selection the boy was detained by the Chinese authorities and has not been seen since; despite Chinese claims that he is now living quietly with his family somewhere in Tibet. The five-year-old son of two Communist Party members subsequently appointed by the Chinese as their choice for Panchen Lama is rejected by devout Tibetans.

Following Dorje’s escape from Tibet, the Indian authorities threw doubt on whether China would have allowed such a senior religious figure to flee. Rumours started circulating that he was a Chinese spy. Indian courts have since recognised a Tibetan exile two years older than Dorje as the legal heir to the role of Karmapa, although the Dalai Lama recognises Dorje as the true holder of the title.

Dorje’s position was further complicated earlier this year when more than $1million in foreign currencies, much of it in Chinese yuan, was found stashed in trunks at Gyuto monastery. Sensational headlines in the Indian press questioning whether he was a Chinese “mole” brought calls from the Dalai Lama and others in the exile community for the money to be properly accounted for.

According to the Karmapa’s entourage the money came from unsolicited donations from devotees trying to help him build a new monastery. The money had not been deposited in bank accounts, they explained, because of the bureaucratic nightmare Tibetans face conducting any transactions in a country where, as refugees, they have little legal status. Even though this explanation was widely accepted, Dorje is still treated with suspicion by the Indian administration, which closely controls public access to him.

Against this background I expect the Karmapa to be extremely guarded. On the contrary he seems relieved to have the opportunity to address the allegations. On a brief visit to the United States in 2008, Dorje, 25, was introduced at one event as “His Hotness” because of his youthful good looks. Much has been made of his reported penchant for video games and X-Men comics.

But on the morning we meet he appears serious and studious in his monk’s robes and rimless glasses, the only nod to worldliness immaculately manicured nails. Seated in a small airy room at the apex of Gyuto monastery, an interpreter at his feet, Dorje is quick to answer the allegation that he is a Chinese spy, describing it as “hurtful to the core”.

“I am a full blooded Tibetan and for any Tibetan to be accused of being a Chinese spy there can be nothing worse. As a practitioner of Buddhist Dharma I have trained not to harm others. So to say that I came here to harm India and threaten national security, nothing can make a deeper wound,” he says. “When I escaped Tibet I was prepared that I could be killed at any moment so I was prepared for feelings of concern and fear and doubt. But I was not prepared for what I have had to face here. For anyone this would be difficult to forget.”

When I ask the Karmapa what he thinks of one of the possibilities suggested to me by Tenzin Takhla, that he could one day become the next Dalai Lama, Dorje dismisses it saying “No-one can be the Dalai Lama except the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation. He is the one and only.” He has heard nothing, he says, of the imminent discussions to consider the Dalai Lama’s eventual spiritual succession. In the past the Dalai Lama has also raised the prospect that the role could die with him if the Tibetan people felt they had no use for another Dalai Lama after his death. He has also spoken of the possibility of a female successor, adding that if this were to happen he hoped the woman would be beautiful.

Following the Chinese government’s decree that only it can decide who will succeed the Dalai Lama, however, the prospect of a “duel of the Dalai Lamas” in future looms. Dorje says he is confident the Dalai Lama will make a very clear statement about his spiritual succession when the time is right “so there will be no opportunity for manipulation.” Sangay too is adamant that if the Chinese authorities appoint their own Dalai Lama they will fail “just as they are failing with their Panchen Lama,” who he describes as “a parrot in a golden cage in Beijing.”

For a culture based on Buddhist principles of tolerance, compassion and non-violence, however, all this uncertainty over the future direction of both spiritual and political leadership augurs gathering storm clouds over Tibet. For all the Dalai Lama’s messages of peace in evidence there is now a more forceful mantra pinned up everywhere in Dharamshala. “No matter what is happening. No matter what is going on around you,” it reads. “Never give up! Never give up!”

Photographs by Daniel Berehulak

Endangered Species

13th March 2011

13th March 2011

It’s the lonely heart of the bird world, pushed to the brink of extinction by human greed and its own choosy habits. As a new film depicts one parrot’s happy search for a mate, Christine Toomey follows the distressing real-life saga of Spix’s macaw

As we twist and turn through a labyrinth of back lanes on the outskirts of Puerto de la Cruz, not far from northern Tenerife’s well-worn tourist track, the two scientists by my side are only half-joking when they say they are trying to disorient me. When I ask the name of the road they become nervous: “You’re not going to print that, are you?” one asks. Rolls of razor wire loop across a tall concrete wall embedded with jagged glass and surrounded with banks of infrared security cameras. Heavy steel gates slide open to reveal huge mesh cages containing some of the rarest creatures on earth. So precious are they, and so great is the fear for their safety, that not one is on public display anywhere in the world.

At first they’re hard to spot among the vegetation. But then, with a flutter of turquoise wings, two exquisite parrots emerge and fly towards us. Meet the Spix’s macaw, the world’s rarest bird. Gram for gram they are worth more than heroin and many precious gems. These parrots, named after the German naturalist who discovered the species, have been hunted to extinction in the wild. The last Spix’s macaw seen in the wild, in Brazil’s northeastern state of Bahia, was dubbed the “world’s loneliest

bird” when it was spotted flying alone through the jungle in 1990. For 10 years it was seen swooping through the trees in a forlorn attempt to find a mate. Despite conservationists’ desperate efforts to pair it with a captive bird released into the wild, the lonely-heart macaw was last seen on October 5, 2000, and after presumed dead.Now the sorry tale has been retold in a multimillion-pound 3-D animation film. Rio has voice-overs by Anne Hathaway, Jesse Eisenberg and Will.i.am. Produced by 20th Century Fox and Blue Sky Studios, it is the creation of the Brazilian director Carlos Saldanha, 42, whose Ice Age: Dawn of the Dinosaurs is one of the top 20 highest-grossing films of all time. Mindful of the sensitivities of cinema-goers, Saldanha admits his film is “different from reality — it has a happy ending”.The true story is, as James Gilardi, director of the World Parrot Trust, puts it, “a tale of human greed run amok”. There are approximately 85 Spix’s macaws left alive in the world, and most of those are in the private hands of wealthy collectors. Fifty-six are owned by a billionaire sheikh in Qatar, three by a wealthy businessman in Berlin. The nine hidden away at the Loro Parque Foundation in Tenerife are kept there on behalf of the Brazilian government. A few others are in private aviaries, coveted as exotic trophies.

The story of how the Spix’s macaw came to be in such a precarious position is a salutary tale about mankind’s disregard for other species. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), roughly one-fifth of the world’s vertebrates are now listed as endangered, including 13% of all bird species.

“Trying to bring a species back from the brink is far more difficult if they have been left to go extinct in the wild,” says David Waugh, director of the Loro Parque Foundation. To appreciate why, you need to know more than you might like to about the sex lives of parrots.

Tony Juniper is the British environmental campaigner who co-led the expedition to track down that last lonely Spix’s macaw. One problem he faced was the difficulty in telling if it was male or female. Like many parrots, Spix’s macaws are “monomorphic”. To the human eye, the sexes appear identical. Parrots, on the other hand, have no trouble identifying each other: they have a broader visual spectrum of colours than humans. For the movie, Saldanha took creative liberties, making the captive male a vibrant blue all over while giving his wild love interest the more accurate colouring of a paler blue-grey head. When the real-life plot was hatched to release the captive bird in the same area of Brazil as the single wild bird, it took lengthy analysis of dropped feathers by scientists at Oxford University to determine that the lonely creature was male.One reason many parrots are monomorphic is that they pair for life, so few need to attract new mates. In captivity they show similar loyalty to humans. This, with the destruction of their habitat, explains why parrots are the most endangered bird family on Earth; of roughly 360 species, only four, including the budgerigar, are not listed as conservationists chose as a potential mate for the last lonely wild male.After being cooped up in a cage for years, the selected female needed an intensive fitness-training programme before she could be released into the area of forest from which she had been snatched. The two birds flew together for just a few months before she flew into an electricity pylon and perished. In the lonely years that followed, the last wild male temporarily teamed up with a smaller green female parrot of an entirely different species. The pair mated, but none of the hybrid eggs survived. Now just a small number of captive Spix’s macaws survive.

So many rumours abounded as to where some are, that when a pet owner made a call to a vet in Denver, Colorado in 2002 requesting help for a “Spix’s macaw”, it was dismissed as a hoax. The woman, whose identity has never been revealed, was asked to take a picture of the parrot posing alongside that day’s newspaper before specialists would believe her. When a vet went to the owner’s house, she found the parrot pining and listless.The woman had named her pet Presley after the singer’s blue suede shoes. He was in a sorry state. The perches of his cage were so wide that he had been forced to stand flat on his feet, so his legs were weak and his balance poor. Fed on an inadequate diet of commercial pellets, he was bad-tempered and difficult to bathe, his feathers were in bad shape and his beak misshapen. He no longer remembered how to fly. Presley’s owner, who told authorities the bird had been left with her in the late 1970s, had no idea how old he was. (Parrots can live for 50-60 years.)

Presley’s discovery caused quite a storm in avian circles. Despite his poor health, he was hailed as a welcome addition to a breeding programme set up in 1990 eventually incorporating all known birds of the species, even those in private hands. Many were related through having been bred in captivity; Presley constituted “fresh blood”. Hopes were high that he would breed with a captive female.

So Presley was bundled into a cage, tucked under the arm of a Brazilian conservationist, and flown back to his native land. After some debate he was paired with a female at a privately run parrot-breeding centre near Sao Paulo. Press reports about Presley being flown back to Brazil helped fire Saldanha’s imagination.

“I found it really touching. The sad truth is that many birds become so domesticated they can never be returned to the wild,” he says. His animated hero fares better. Saldanha portrays the male lead, Blu, eventually flying off into the blue yonder with his newfound female friend to procreate discreetly.In real life Presley wasn’t so lucky. Optimism about his sexual prowess proved unfounded. His advanced years were no obstacle, but he couldn’t get it on. Or rather, he couldn’t get on and stay on. Parrots don’t have penises, so they must perform a delicate balancing act to ensure their semen is deposited in exactly the right place to fertilise a female’s egg. Unused to flying, Presley couldn’t extend his wings enough to stay in the right place.The frustrated breeders eventually gave up and paired him with a parrot of a different species for company. Recent visitors to the breeding centre where he is kept — the Lymington Foundation near Sao Paulo — say he appears “cranky”. Some experts have advocated storing his genetic material so that his genes could be passed on by artificial insemination, or by cloning if it became possible to clone birds. But this is where politics, ego and human pride come into play.

“The problem is that the Spix’s macaw is probably the most politically contentious bird that ever existed,” Waugh explains. Although there are only five Spix’s macaws left in Brazil, including Presley and two pairs at a facility attached to Sao Paulo Zoo, all decisions regarding the breeding of the remaining known birds have to be approved by an international committee — called the Working Group for the Recovery of the Spix’s Macaw — overseen by an environmental division of the Brazilian government.”As far as some politicians are concerned, the Spix’s macaw is part of the natural patrimony of Brazil,” says Waugh, whose foundation handed ownership of its birds back to their native country on the understanding that it continue to breed them at the Tenerife facility. In the past, co-operation totally broke down, with acrimony between private owners sinking the survival of the species into grave doubt.In 2002 the original committee set up to oversee the breeding was dissolved by the Brazilian government when Wolfgang Kiessling, the German founder/owner of Loro Parque, and others became outraged over the unauthorised “transfer” of four parrots from a private breeder in the Philippines to Sheikh Saoud bin Mohammed bin Ali Al-Thani, a member of the ruling family of Qatar. Speculation was rife that vast sums of money had changed hands.

Sheikh Al-Thani is an avid collector renowned for paying handsomely to own the rarest of the rare; in 2000 he is reported to have paid nearly $9m for a hand-illustrated copy of Audubon’s Birds of America — more than double the sum auctioneers estimated the book would fetch. A passionate nature-lover, the sheikh runs a state-of-the-art breeding centre, Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation, on a “farm” of 2.5 square kilometres where he keeps rare Arabian oryx, cheetahs and other endangered species.Al-Thani displays a picture of himself with two Spix’s macaws perched on his arm on Al Wabra’s home page. The provenance of some of the 53 birds of the species he now owns is unclear. Kiessling claims the sheikh came to see him in the late 1990s in Tenerife, claiming he had been visited by a man from Pakistan who had thrown a hessian sack onto a table in front of him containing 11 blue parrots of another protected and extremely rare species, the Lear’s macaw. Kiessling claims the sheikh wanted to know how these birds could be “legalised”.