March 11, 2007

March 11, 2007

Investigation

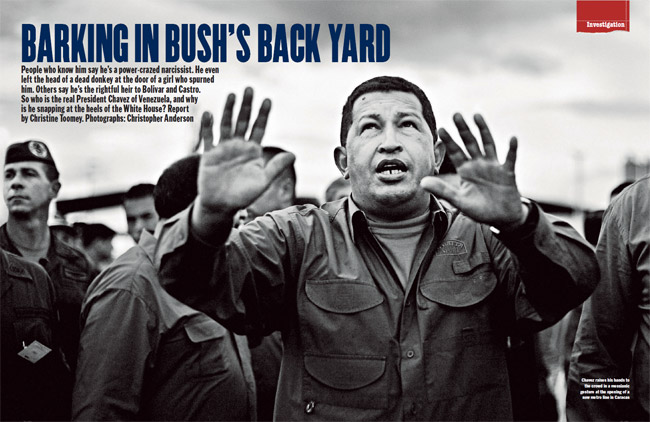

People who know him say he’s a power-crazed narcissist. He even left the head of a dead donkey at the door of a girl who spurned him. Others say he’s the rightful heir to Bolivar and Castro. So who is the real President Chavez of Venezuela, and why is he snapping at the heels of the White House? Report by Christine Toomey

Late at night, Doña Elena Frias de Chavez invites me to follow her into her bedroom in the hacienda-style governor’s mansion on the outskirts of Barinas, a remote regional capital in Venezuela’s central high savanna. Skirting round her unmade bed, past photographs hung with rosaries of her controversial son, the Venezuelan president, Hugo Chavez, she signals to me to stop. I turn to see a makeshift altar set into an alcove crammed with candles, statues of the Virgin Mary, saints and dusty artificial flowers around a large hologram of Jesus Christ, the eyes of which appear open or closed depending on where you stand.

“This is where I pray when I fear for the life of my son,” says Doña Elena as she brings her hands together with a slight bow, then lightly touches the glass surrounding a lit votive flame. “I make sure there is always at least one candle alight here. I even get up in the night to check that it has not gone out.”

In the week that his opponents’ hatred is so intense that Chavez is depicted in the opposition press as a modern-day Hitler under headlines such as “Heil, Hugo!”, Doña Elena has cause to pray a great deal. Five years ago, when the fury of his opponents reached fever pitch, and bloody clashes on the streets of Caracas left dozens dead, Chavez was seized by soldiers and held under military arrest. That coup attempt, which many claim was backed by the CIA, was short-lived.

Less than 48 hours later, the former paratrooper, who had led a failed coup himself a decade earlier but finally came to power after being elected, emerged on a balcony of the Miraflores presidential palace clutching a crucifix and declaring that the will of the people had returned him to power. “It was the work of God that saved my son on April 11th and 12th,” says Doña Elena of those two days in 2002. “But Hugo has so many enemies I must pray long hours.”

This intense devotion when I visit her in late January is to counter renewed opposition rage, this time at her son’s announcement that he was passing a new law to enable him to rule Venezuela by decree for the next 18 months, paving the way for what he calls “maximum revolution” and “21st-century socialism”. These sweeping powers were granted him by a congress wholly loyal to him after the opposition boycotted elections over allegations of fraud and intimidation. The law gives Chavez free rein to introduce further nationalisations to those already announced; to gain greater state control of the petroleum industry in a country that is the fifth largest oil producer in the world; to further control the media after closing down the largest opposition-run TV channel; to reduce the authority of state governors, mayors and other officials; and to loosen restrictions on the re-election of the head of state – ie, himself. Opponents branded the announcement “totalitarianism lite”.

One former Chavez ally, Teodoro Petkoff, now editor of the newspaper Tal Cual, which ludicrously compared conditions in Venezuela to the early days of the Third Reich, decried the new law for “liquidating obstacles to absolute power”. “This regime is now technically an autocracy. That does not mean it is a dictatorship, but the prerequisites for dictatorship exist,” said Petkoff as he put the finishing touches to a front page depicting Chavez with a Hitler moustache.

In Latin American politics, such mudslinging is nothing new. Chavez himself is a master of the rhetorical flourish. When I come face to face with him, as he holds forth for over four hours in the presidential palace in what is loosely dubbed a press conference, Chavez delivers one of his trademark verbal sideswipes at his favourite target, George Bush. He describes him as “more dangerous than a monkey with a razor blade”.

As the assembled press wilts in the heat, a bow-tied butler discreetly delivers Chavez silver platters bearing cup after cup of espresso coffee, of which the president is reputed to drink more than two dozen a day to stay on form.

Chavez rarely grants interviews, preferring instead to deliver lectures – punctuated by the flourishing of fluorescent pens, tirades against Bush (to confirm his position as a global icon of anti-Americanism), jovial storytelling and the occasional song. Since he had just visited Cuba’s ailing president, that day’s outpourings also contained many references to his close friend Fidel Castro.

Hysterical references to Hitler aside, it is Castro with whom Chavez is most often compared. With his talk of turning his country into a socialist utopia fit for the 21st century – albeit one inspired by Venezuela’s 19th-century liberator, Simon Bolivar, with whose spirit he is claimed to commune – many refer to Chavez as Castro’s heir apparent. This prospect of another political bogeyman in their back yard has prompted US leaders to denounce Chavez as a dangerous demagogue potentially much more threatening than Castro. While the Cuban leader could once count on the support of the former Soviet Union to punch above his weight on the world stage, Chavez controls a far bigger and wealthier country than Cuba: one with the largest oil reserves outside the Middle East.

The US has virtually ignored Latin America for more than a decade. But alarm bells have been ringing since Chavez started dipping into Venezuela’s public coffers to cultivate economic and political alliances worldwide, not least among arch-foes of the US such as Iran.

Yet when I talk to Doña Elena about her son being portrayed as a future Castro, the strict former schoolteacher’s eyes flash with anger. “Just because they are good friends does not mean my son should be seen as his successor,” she says, pulling at her jacket’s hem in agitation. “My Hugo Rafael does not want to see the same old story of communism repeated here. Only someone with the head of a donkey could think he does.” It’s an unfortunate turn of phrase in the light of a story I hear later about Chavez’s youth.

“My son is an immensely religious man. Why else would he have sought the benediction of the Pope?” Doña Elena continues, as she points out several photographs showing Chavez smiling broadly beside Pope John Paul II. While looking at the photographs, I realise from his polite cough that I am obscuring her husband’s view of the TV. As I move, the amiable Don Hugo de los Reyes Chavez props his head on his hand to continue watching a baseball game.

“My son gets his tough character from me. His father has a more placid temperament,” Doña Elena says in a low voice as we leave the room. For the past six years, her husband, also a former schoolteacher, has been governor of the vast cattle-ranching and oil-rich state of Barinas in the country’s high plains, Los Llanos. Stretching from the foothills of the Andes to the Orinoco river, Los Llanos are seen as the country’s spiritual heartland, and those born here – llaneros – are fiercely independent and tough.

When Doña Elena finally says farewell on the colonnaded veranda of the governor’s mansion, close to midnight, I notice an imposing oil painting of Chavez with the outline of a llanero cowboy in the background. “Like me, my son is very generous to those he likes but very tough on those he doesn’t,” she says, pressing a tin of biscuits into my hand as a parting gift.

Until shortly before Chavez became president in 1998 – he was re-elected last December – his family lived in extremely humble circumstances. But since his rise to prominence, not only his father but four of his five brothers have assumed positions of power in Barinas. Critics claim the family are running the state as their personal fiefdom. One brother is mayor of the small town of Sabaneta, where Chavez was born, another is secretary of the state of Barinas, yet another manages key sporting events, and the fourth s in finance. His older brother Adan, a former presidential chief of staff and ambassador to Cuba, is the country’s minister of education. A cousin is director of the state oil company, PDVSA.

As I travel across the flat landscape to Sabaneta the next morning to meet Chavez’s brother Anibal, the mayor, it strikes me that growing up in a place with such far horizons might lead to a tendency to harbour large ambitions. “Certainly Hugo was the one with big plans. He was clever, a born leader. It was always clear he would go far,” says Anibal.

Before agreeing to talk, the mayor insists on an extraordinary ritual. Summoning three assistants into his office, he pulls out a Bible and they all stand waving their hands in the air in evangelical fashion while one of the three ?reads out a passage from the Old Testament: Proverbs, chapter 14, verse 3, which includes the words “Proud fools talk too much”.

“My mother wanted my brother to become a priest,” says the mayor, finally inviting me to sit. “He was an altar boy. My brother believes in God. That is why he will not become like Fidel Castro, who does not. Tell your readers they need have no fear. My brother is committed to free elections. He does not want to see Venezuela become another Cuba. He just wants to see a country more committed to people than profit, a place where spiritual values are more important.”

The first admission from the family that all is not quite as straightforward and uplifting as this comes from the president’s great-aunt Brigida, who also still lives in Sabaneta, and who directs us to the spot on the outskirts where Chavez was born in a straw-roofed, dirt-floor shack. “Hugo did a lot of things in secret because his parents were against them,” she says. “He signed up for the military aged 17 without their knowing. I was one of the first he talked to about his communist beliefs,” says the 64-year-old, who belonged to a banned socialist party in the 1970s.

In the days that follow, I talk to Chavez’s old friends and those who know him even more intimately: his former long-term mistress and his one-time psychiatrist. A more disturbing picture emerges, in which all not being what it seems with Chavez becomes a recurring theme.

Leonardo Ruiz’s wide girth heaves with laughter as he recalls how, as boys, he and Chavez used to play baseball with a ball made of rags or bottle caps. “We couldn’t afford a proper ball. But that was Hugo’s real passion – baseball. He wanted to become a professional player. He only joined the paratroopers because they had a famous pitcher coaching their baseball team.”

This is borne out by all who know Chavez. Less known is the early schooling in communist ideology that he received at the house of this childhood friend, whose father founded the Communist party in Barinas. “It was really my father and older brother Vladimir who introduced Hugo and Adan to these political ideas,” says Ruiz. “They came here to talk and read our books. But they had to hide their communist sympathies because it was dangerous.”

An aside Ruiz makes as we are parting leaves me feeling uneasy. Having read an account of a macabre incident from his youth in a bestselling book about Chavez by two Venezuelan authors, Alberto Barrera and Cristina Marcano, I ask Ruiz if he recalls it. It concerns Chavez and his friends being spurned by an attractive girl when they were teenagers. Out of revenge for the slight, Chavez is said to have cut the head off a dead donkey and placed it on the girl’s doorstep. “Oh yes, that joke,” says Ruiz, looking uncomfortable. “I admit it was in bad taste.”

Struggling to reconcile Ruiz’s account of Chavez as a secret communist with a taste in jokes verging on sadism with his mother’s description of him as a devout Christian, I later speak to a woman who once shared his bed. Herma Marksman, a history professor at a Caracas university, admits she has had no contact with Chavez since shortly after he became president. But the two were lovers for nearly 10 years while Chavez was plotting to overthrow the corrupt government of the then president, Carlos Andres Perez, who was deeply unpopular among the country’s marginalised poor.

The failed military coup against Perez in 1992 followed anti-government riots three years earlier which had left many hundreds dead. Chavez had been plotting for years to install a revolutionary junta under the command of a group he and his co-conspirators called the Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement. Seizing this moment of violent social unrest, the group tried to take control of strategic locations around Venezuela, including Miraflores Palace, but Chavez was quickly surrounded and so surrendered. Before being taken into custody, he was allowed to make a short television address to persuade his fellow rebels to lay down their arms. A striking figure in his red paratrooper’s beret, he announced: “Comrades, the objectives we set for ourselves have not been possible to achieve now. But new possibilities will arise again.”

He was sentenced to long-term imprisonment, but the 32-second broadcast still made him a hero to the poor. As far as most Venezuelans were concerned, it was only a matter of time before he would attempt to seize power again.

Nine months later, Chavez’s allies staged another, even bloodier coup attempt. Miraflores Palace was bombed from the air. More than 170 people died in street battles. Within months, Perez was impeached on corruption charges. The following year, 1994, Chavez and his fellow rebels were freed from jail. Joining forces with several leftist civilian parties, he and his military allies launched a new party, the Fifth Republic Movement. Four years later, Chavez stood in presidential elections and won.

Marksman, a respected historian with links to many of Chavez’s leftist contacts, was his lover from 1984 to 1994. “We were all idealists then. Our goals were to tackle corruption and build a prosperous Venezuela based on justice for all. There was none of this idolatry of Fidel or Che [Guevara],” says Marksman, a beautiful brunette in her youth and the woman for whom Chavez reputedly wanted to leave his first wife, the mother of his eldest three children. “But we were all deceived. We’re now heading for a totalitarian regime. He [Chavez] is sacrificing the resources of future generations with money that is not his. Little Red Riding Hood has turned into the wolf. He is astute and manipulative and not religious at all. But he realises that brandishing a crucifix will bring him closer to a certain social class. It is a blasphemy.”

Such an outpouring could be dismissed as the vengeance of a scorned woman. When Chavez emerged from jail as a hero, he was surrounded by adoring women and separated from both his wife and his mistress. A second marriage, which produced a fourth child, also ended in separation. Yet Marksman is generous in her praise of him as an attentive lover. She believes the seeds of what she sees as the very destructive path on which Chavez is headed were sown in a childhood far less idyllic than that painted by his family.

“He was very marked by his upbringing. He had a terrible childhood. His mother was very severe. His family background was very humble. I believe this sowed a lot of resentment in his character,” she says, recalling Chavez telling her that he once met his mother in the street when he was growing up and, having not spoken to her for years, turned and walked in the opposite direction. For much of his youth he did not live with his parents. So straitened were the family’s circumstances that both he and his elder brother Adan were brought up by their paternal grandmother. “While other small children were out playing, the two brothers were sent out on the streets to sell sweets their grandmother made to make ends meet,” says Marksman. Chavez talks publicly about his peasant background, but Marksman says it left him with “fundamental frustrations”, a trait now playing itself out, she believes, in the unpredictability and increasingly authoritarian way in which he wields his power.

It is an interpretation borne out by another person who was close to Chavez, the man who invited him to share his home and make use of an office for several years when he was released from prison. Nedo Paniz, an urbane professor of architecture with a studio in a wealthier neighbourhood of Caracas, sympathised with Chavez’s fight against corruption. But, like Marksman, he says he has had no contact with Chavez since he assumed power: “As soon as someone is no longer of use to Chavez, he is disposed of. He moves from oasis to oasis, leaving personal and political corpses along the way.”

Pinned on the architect’s wall is a note from another former ally of Chavez who was crucial in easing the former paratrooper’s transition from failed coup-plotter to aspiring politician. Luis Miquilena, a one-time communist union leader who became Chavez’s first interior minister before they fell out, summarises the president’s character as “impulsive, temperamental, intellectually limited, surrounded by obsequious yes men, completely disorganised in every aspect of his life, ignorant of the economy, a lover of luxury, and more than anything else erratic – one of the most unpredictable men I have ever known.”

Given that the two men are now enemies, you would hardly expect a glowing reference. But again it is the more personal observations that ring true. “His background left him with feelings of social resentment, a sense of ‘I don’t have what others have,'” says Paniz, who is more worried, however, by Chavez’s obsession with Simon Bolivar, the country’s national hero: “He used to engage in spiritual sessions with the soul of Bolivar. He believed our liberator had somehow entered his being. So now he stamps everything he does with the mark of Bolivar.

“But to constantly refer back to a glorious moment in our history 200 years ago is madness. It is this combination of madness and his free access to this country’s vast wealth that is, I believe, very dangerous.”

Paniz says that during the years he and Miquilena helped groom Chavez for power, both men began to doubt his stability and suitability for public office. “Just before the election in 1998, I remember I turned to Miquilena and said to him, ‘I am very afraid we are creating a monster.'” Paniz recalls the elderly man’s reply: “I think the same, but it is all we have.”

Even those considered more objective hint at disturbing tendencies. Dr Edmundo Chirinos likes to be known as the president’s friend rather than as his personal psychiatrist, despite having been called on to counsel Chavez after the breakdown of his first marriage. “The president is a very unconventional man, very impulsive, with few restraints, which could be dangerous except that he is very intelligent,” says Chirinos, speaking in his gloomy penthouse apartment hung with portraits of Che Guevara. “His main motivation, of course, is power. Many people want power. But when you have the strong personality he has, there is no limit to the amount of power you want. He is also a narcissist, but then name me a world leader that isn’t.”

Chirinos does not believe that Chavez is a religious man, “though I think he identifies with Christ as a leader”. There are indeed messianic overtones in some of Chavez’s speeches, in which he talks of “the kingdom of God” as “a socialist kingdom” .

The doctor concludes with the warning, again, that the main flaw in the president’s personality is his impulsive nature. “To stand before the United Nations in New York and say there was a strong smell of sulphur in the air because Bush had been there was an error of judgment, for instance. So was greeting Putin [an expert in martial arts] with a mock karate chop.”

His impulsiveness seems all the more alarming in the light of what I then hear from a man even Chavez refers to as an “objective investigator”. Alberto Garrido, a political scientist who has written over 16 books on Chavez, says: “From his words it is clear he does not believe in God… He is driven by the belief that it is his historic duty to complete the mission of Bolivar.”

Key to this is the vision of a politically united Latin America. Bolivar died disillusioned in 1830, convinced that South America was ungovernable. Chavez believes otherwise. To this end, he is promoting a United Bolivarian Congress of People stretching from South America to the Caribbean. So far, only smaller states such as Nicaragua, Bolivia and Ecuador, where the populist presidents Daniel Ortega, Evo Morales and Rafael Correa have recently assumed power, are loosely signed up. Left-wing leaders of bigger nations, such as Brazil, Argentina and Chile, appear to be keeping their distance. Privately, Brazil’s president, Lula da Silva, is reported to have complained that Chavez is “flirting dangerously with authoritarianism”.

“Whether or not this utopia is realised depends on historical events,” says Garrido. “But what Chavez is doing with great ability is filling the power vacuum in the region left by a United States totally focused on the Middle East.” In his most recent book, Garrido investigates the way Chavez has himself been cultivating links in the Middle East. “He believes in using oil wealth as a strategic weapon. Part of this strategy is the campaign to convince the world’s oil trade to change from petrodollars to petro-euros.”

One concrete result of Chavez cosying up to Iran (he has visited Tehran, and President Ahmadinejad has made several visits to Venezuela) is an accord between the two countries to set up a $2 billion investment fund to help developing nations “liberate themselves from US imperialism”. Chavez, who vigorously defends Iran’s right to develop a nuclear programme, has declared the partnership a symbol of “two revolutions coming together to form a mighty current to defeat the United States”. Ahmadinejad, meanwhile, has also ?been courting ties with Ecuador, Nicaragua and Bolivia in the hope of leading an anti-US bloc in America’s back yard.

Until now, the US has been muted in its response. But high-ranking US officials and congressmen are now pressing the State Department to take a tougher line with Chavez, who they say is “a threat to the US, alongside Al-Qaeda, Iran and North Korea”.

In recent years Chavez has sought to embarrass the Bush administration on home turf by giving free oil to Indian tribal reservations and to poor neighbourhoods of New York. More recently, he has signed a deal with London’s mayor, Ken Livingstone, to provide cut-price oil so that Londoners on income support can have half-price public transport, in return for technical advice on traffic management and recycling in Caracas. Such gestures are dismissed by many as publicity stunts. But there are those who warn that they have more serious intent.

“To really ensure himself the heroic place in history he craves, Chavez needs a grandiose story such as the revolutions of Nicaragua or Cuba,” says the writer Alberto Barrera. “Without that, he has too little history and too much oil money to be another Fidel.” And there’s the rub. Despite all the sabre-rattling against Bush, whom he describes as the “No 1 mass murderer and assassin on the planet” (Tony Blair is an “imperialist pawn sharing Bush’s bed”), Venezuela still pumps nearly 1.5m barrels of oil to the US every day, making it the country’s third largest supplier. It is this vast income that Chavez uses to fund his dream of revolution.

With the price of oil more than trebling since he came to power, he has been able to introduce an impressive range of social initiatives to help Venezuela’s poor. They include a network of health clinics manned by 17,000 guest Cuban doctors; literacy and adult-education programmes; nutrition centres; cost-price supermarkets; and co-operatives providing employment. As beneficial as these schemes are, financial analysts argue that they are almost totally dependent on state handouts and will have to be cut when the price of oil falls. They do little, therefore, to address the fundamental restructuring of the oil-dependent economy needed to ensure long-term change.

With Venezuela awash in oil money, analysts warn that the economy is dangerously overheating. Inflation is running at close to 17%, a consumer boom has pushed foreign imports to a record high, and public debt is nearly twice what it was when Chavez first took power. Economists talk of the president siphoning money out of foreign reserves to curry favour abroad – buying $3 billion in government bonds from Argentina to help the country restructure its debt; buying weapons and aircraft from Russia; and making oil deals with China. Yet changes to the way statistics are kept in the country make it impossible to assess the real state of the economy, they argue. In the words of one analyst, “It is fair to say this is now a country without audit.” Even with the country’s huge wealth, some predict that fiscal imprudence will soon lead to a scarcity of basic goods; on the way to the airport I hear the news announcing a shortage of sugar.

As long as the oil bonanza in this country of 25m lasts, Chavez can do no wrong in the eyes of Venezuela’s poor majority. Yet walking through the streets of one of the poorest barrios in Caracas – the 23 de Enero neighbourhood, where Chavez himself votes – in the days after the president announces he will rule by decree, I sense vague rumblings of discontent.

“We love Chavez. He has made the poor count in this country… He pays for things like this,” said Reddy Zorsano, a railway worker who is watching his daughter twirl her baton in a children’s street parade. “But we won’t accept a totalitarian regime. He is only in power because we put him there. We worry about the future of our children, their education, rising crime.” Oil wealth has fuelled record levels of crime, giving Caracas reputedly the highest murder rate per capita in the world.

But sitting just a few feet away from Chavez in the presidential palace as he delivers a shortened version of his weekly televised address to the nation, called Hello Mr President – a one-man show in which he has been known to speak nonstop for up to eight hours – I get the sense that he won’t be leaving the world stage for some time yet.

What he might lack in economic sense and, increasingly, political savvy, Chavez attempts to make up for with charisma and charm. “And in Venezuela this goes a long way,” says Alberto Barrera. “People here love him because he is getting paid for what everyone aspires to – not doing much, telling jokes and talking a lot.”