April 4, 2004

April 4, 2004

Investigation

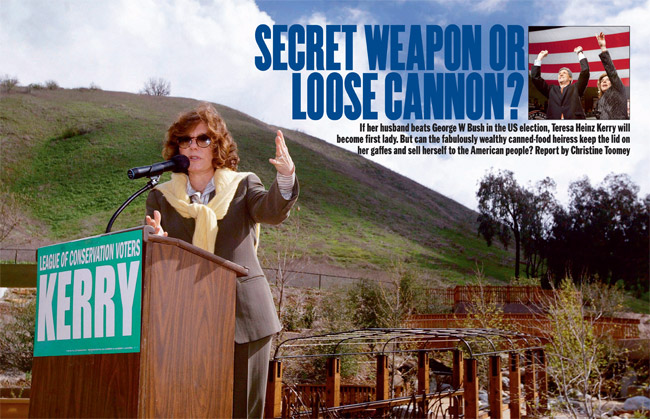

If her husband beats George W Bush in the US election, Teresa Heinz Kerry will become first lady. But can the fabulously wealthy canned-food heiress keep the lid on her gaffes and sell herself to the American people?

Sitting on a shelf in Teresa Heinz Kerry’s comfortable Washington office — just a stone’s throw from the White House, but more like an intimate sitting room than a hub of the $1-billion-plus Heinz food empire of which she is the ruling matriarch — are two pop-psychology manuals by the bestselling author and psychiatrist M Scott Peck. Under the heading Problems and Pain, the opening line of The Road Less Travelled puts the dilemma of human existence simply: “Life is difficult.”

It is a verdict Heinz Kerry feels does not go far enough. As she addresses a select crowd in a large private home in Fairfield County, Connecticut — an area favoured by Wall Street bankers and rich financiers — while drinks flow at a private bar at one end of the room, she can’t help but bemoan her lot. “This is not life. It is an existence. It has a beginning and an end,” she says in a soft Portuguese accent, before rushing off to a $1,000-a-head dinner in nearby Greenwich.

Ever since her second husband, the Massachusetts senator John F Kerry, became a Democratic challenger for the US presidency, his wife, also his second, has taken to the road to campaign on his behalf. And though the rigours of the campaign trail are softened by having her own ketchup-red-and-white Gulfstream jet (named the Flying Squirrel, with the number 57 painted on its tail fin), she is not finding it easy.

Bombarded by cameras and quizzed incessantly wherever she goes, she has found herself under the media microscope and, with the election more than six months away, the scrutiny has only just begun. But already there have been worrying headlines. “Teh-Ray-Zah the Terrible” ran one article in the Philadelphia Daily News in February. “Is Teresa Heinz an asset or an Achilles’ heel?” asked the Los Angeles Times more recently, followed by a piece in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram with the headline “Linchpin or Liability?”

Much has been made of Heinz Kerry’s tendency to speak her mind — acknowledged by many as both refreshing and engaging in a political fray where double talk is often the order of the day. But then there are — according to one who knows her well but prefers not to be named — her “Marie Antoinette” moments.

First there was the time Heinz Kerry looked aghast when asked if she’d insisted on a prenuptial agreement before marrying for the second time. “Of course. Everybody has a prenup,” she stated blithely. “You’ve got three kids with somebody else, you’ve got to have a prenup.” Then she said of cosmetic surgery, “When I need it, I’ll get it,” after admitting to wanting another shot of Botox “soon”. Finally, there was the time she described her second husband as being “like a good wine” that takes time to mature. “Then it gets really good and you can sip it,” she said, adding that she believed John Kerry was “at that stage now”.

None of the above would, under normal circumstances, merit even a mention. After all, when her first husband, John Heinz — also a US senator and sole heir to the Heinz family fortune — died, she became one of the richest widows in the world. Circumstances, however, are anything but normal. November’s presidential election looks set to be a very closely run race. Aside from critical concerns over national security, the key issue on which it will turn is almost certainly the dismal state of the US economy.

Over the past four years, nearly 3m Americans have lost their jobs. This means John Kerry’s chances depend largely on winning the votes of struggling blue-collar workers in key states such as Ohio, Michigan and Missouri in the Midwest. Workers who voted Republican last time but have fast lost faith in George W Bush; workers with no need for prenups and no money for cosmetic surgery, Botox or fine wines.

So, are Heinz Kerry’s “let them eat cake” lapses likely to cast a shadow over her husband’s chances of making it to the White House? With the US more bitterly divided and polarised than at any time in recent history, most predict this election will be one of the most viciously fought ever, and Heinz Kerry is certain to be caught in the crossfire. When asked if she is scared at the prospect, she laughs and brushes back a thick shock of auburn hair from her forehead. “Scared?” she scoffs. “I lived in a dictatorship. I marched against apartheid in the late 1950s. What am I scared of? What I do is put up a mirror and let them [my critics] see their faces. They can stoop as low as they want. But I will stay up here.”

The reference to her colonial childhood already marks her out as different from the spouse of any previous presidential contender. But Heinz Kerry knows well that she has at her disposal a weapon much more powerful than a hand mirror. Although federal law prevents her from making a contribution of more than $2,000 to her husband’s campaign, if attacked personally she is fully entitled to tap into her vast fortune to mount a defence. “If the honour of myself or my family is trashed,” she has vowed, “I will fight to redeem it.”

She may now be a grandmother of 65, who often describes herself as “shy”, but Teresa Heinz Kerry is anything but retiring. While many women who inherit a fortune — in her case, personal assets worth $500m — wallow in the comfortable existence of the so-called “ladies who lunch”, she has forged a role for herself as one of America’s leading philanthropists. She now heads the Heinz Endowments and the Heinz Family Philanthropies — foundations with combined worth of around $1.2 billion.

“Teresa doesn’t need the White House,” says Phyllis Magrab, a professor of paediatrics at Georgetown University in Washington and a longtime friend. “Some people have needed it to catapult them into the public eye. But Teresa can be in the public eye any time she wants.”

She might not need the White House; the question is, does John Kerry need her to get there? Many believe he does. To understand why and appreciate what is driving her to help him, you need to look at the road she has travelled, problems and pain included, since her childhood — most of which was spent in Mozambique.

Born Maria Teresa Thierstein Sim›es-Ferreira in Mozambique’s capital, Maputo, at a time when the country was an overseas province of Portugal — then under repressive dictatorship — Heinz Kerry refers to herself as a “daughter of Africa”. She often talks with nostalgia about the time she spent travelling around that country as a child with her father, a Portuguese doctor who had moved to Mozambique to practise tropical medicine. Some of her happiest memories, she says, are from this period spent “in the bush with a cement floor and a thatched roof” observing her father treat patients, many of whom had queued up outside his surgery since before dawn.

Her father had wanted her to become a doctor too and, she confesses, she sometimes regrets that she did not. But in the circles in which she moved, there were few role models of women successfully combining careers with being wives and mothers and she knew she wanted to raise a family. Great emphasis was still placed on her education, and at a young age she was sent away to a strict Catholic boarding school run by British nuns in racially segregated South Africa. She went on to attend university there, which is when she took part in early anti-apartheid demonstrations. She then went to Europe and trained as an interpreter in Geneva, where she was a classmate of Kofi Annan. She speaks five languages fluently.

Though privileged in many ways, her early life was also marred by tragedy. When she was a teenager her mother was diagnosed as having a rare form of cancer that slowly deformed her facial features and led to 26 operations over the following 40 years before the disease eventually spread to her brain. When she was in Geneva her younger sister, Gita, who had come to live with her and study, was killed in a car accident while driving to Portugal. As the only relative nearby, she was called on to identify her sister’s body.

But it was also in Geneva that she met her first husband — a Harvard student working there on a summer secondment at a Swiss bank. All she knew about his background when they first met, she says, was that his father “made soup”. It was a few weeks before she discovered he was a descendant of Henry J Heinz, who founded the “57 varieties” multinational food empire. After returning to live with her parents for a year as the family mourned her sister’s death, she moved to the US to work as an interpreter with the United Nations and be closer to John Heinz. The couple married in 1966, had three sons and, in the same year that John Heinz was elected to Congress as a Republican senator from Pennsylvania — 1971 — she became an American citizen.

For the next two decades the family split their time between Washington, a farm on the outskirts of Pittsburgh and retreats in Sun Valley and Nantucket. But the man she still calls the “love of my life” was killed shortly after the couple’s silver wedding anniversary in 1991. When the plane in which he had been flying developed problems with its landing gear, a helicopter sent up to examine its undercarriage collided with it, killing all on board. The two aircraft then crashed into a school playground, crushing two children to death. With customary candour she admits she made it through the next year with the help of Prozac.

Since her husband had been an only child, at the age of 52 she not only inherited a vast personal fortune, but also took charge of one of the world’s largest charitable trusts. Rejecting an invitation to stand for her dead husband’s Senate seat, she set about reorganising the foundations by focusing them more sharply on support for issues she felt strongly about, such as early childhood education, affordable health care, women’s retirement and the environment. She also founded the annual Heinz Awards and continues to play an active role in handing out grants, awards and endowments worth approximately $70m a year to leaders in the fields of science, arts and education. “I don’t make money in my office,” she says. “I give it away.”

At the time she was being courted to enter politics, she described political campaigns as the “graveyard of real ideas and the birthplace of empty promises”. She also said she thought being first lady would be “worse than going to a Carmelite convent”. But this was before she got to know John Kerry. The couple had first met, briefly, when they were introduced by her first husband on the steps of the Capitol. They met again the year after Heinz died, at the Earth Summit in Brazil.

On their third meeting at a Washington dinner the following year, Kerry, a decorated hero of the Vietnam war, offered her a lift home and on the way asked if she had ever seen the Vietnam Veterans Memorial at night. “People were praying. People were crying. He didn’t say anything,” she remembers of that evening. After that she started seeing more of Kerry, who, divorced from his first wife, was known for a number of high-profile relationships with women including the actresses Morgan Fairchild and Catherine Oxenberg. Although she describes him as having been “skittish” and “very, very slow on the uptake in the beginning”, the couple married on Memorial Day weekend in 1995. “If he hadn’t asked me I would have bashed him over the head,” she once admitted.

The merging of the two families has been described by one of the five step-siblings as “difficult” in the beginning, and Heinz Kerry has admitted that she is “real needy”. It was only after Kerry entered the race for the presidency that his wife added his name to her own. “Politically, it’s going to be Teresa Heinz Kerry, but I don’t give a sh**, you know?” she says, adding that “swearing is a good way to relieve tension”.

More problematic for her husband, however, was the fact that Heinz Kerry remained a registered Republican. Although she would “go down the aisle” with him, she said she “wouldn’t cross the aisle”, meaning she would not become a Democrat. She only relented last year, changing her political affiliation with the rather grudging comment that she’d “rather just be independent, but then I couldn’t vote for my husband”.

Such outbursts have led at least one political strategist to observe that, if Kerry does make it to the White House, his wife would be “the Sharon Osbourne of first ladies”. “She is certainly a wild card,” says the Republican pollster Frank Luntz. “I think she will be very controversial. As far as the Republicans are concerned, they can just sit back and laugh, regard her with amusement.”

Continued on page 2

()Secret weapon or loose cannon? (continued)

While the Republicans deny that they will make an issue of her beyond questioning how “appropriate” it is for Kerry to “drag his spouse into the day-to-day dynamic of campaigning”, there are those who believe they are waiting for what has been called a “Muskie moment”. When Senator Ed Muskie, another presidential hopeful in the early 1970s, was goaded by the Republicans that his wife was a drunk, he retaliated by standing in front of a newspaper office to give a speech defending her before breaking down in tears and withdrawing from the race.

Few can envisage Kerry openly displaying such emotion. But there have been moments when he has shown exasperation with his wife. During the couple’s first lengthy joint interview, published in The Washington Post in 2002, when John Kerry said he had not had nightmares about his time in Vietnam “in a long time”, he could barely conceal his annoyance when Heinz Kerry contradicted him. Covering her head with her hands, she mimicked him having a flashback by shouting: “Down! Down! Down!” After that, Heinz Kerry was advised to keep a much closer check on what she said. But, as one former adviser admits, “In reality she defies handling.”

Some argue the spouse of any presidential candidate has very little effect on the way the electorate eventually casts its votes. Others fear there is a danger that if the spotlight is trained too much on Heinz Kerry it will detract attention from the candidate. In the months leading up to March 2’s Super Tuesday, when Kerry finally clinched the Democratic nomination, a serious rift developed among members of his campaign team, which threatened to sink his candidacy. Essentially, it was seen as a falling-out between a group of younger Washington-based advisers and an inner circle of older campaign hands from Boston. Rivals began to dub Kerry’s team “Noah’s Ark” because, as a result of the feuding, it was so split it had two of everything. The dissent was seized on by Kerry’s opponents as a sign of his weakness: if he couldn’t manage feuding factions within his own camp, they argued, how could he manage a country?

One element of this feud was a difference of opinion between the Washington faction and Heinz Kerry about how her husband should be campaigning. The latter prevailed; several of the Washington contingent left or were fired. Since then, Kerry’s team have a more focused idea of how they intend to sell their candidate to the country, and his wife clearly fits into that equation.

Although several points ahead of Bush in many polls, Kerry faces an uphill struggle to maintain that lead. The lackadaisical feel of the operation at Kerry’s campaign headquarters in a run-down town house on Capitol Hill contrasts starkly with the slick re-election machine Bush has up and running in a spacious glass-walled office block in the shadow of the Pentagon.

The opening salvos of the Bush campaign have already been fired. One television clip attacking Kerry’s avowed populism flashed a series of photographs of the various lavish homes he shares with Heinz Kerry and one of a luxury yacht, with a pay-off line copying the MasterCard ad campaign: “Priceless”. It was a signal that their first line of attack will be to condemn Kerry as elitist and out of touch with mainstream America. His mother was a member of the Forbes family — founding members of the high Boston “Brahmin” caste. His father, of east-European Jewish descent, was a diplomat, who sent his son to be educated in Switzerland, then private schools in New England and Yale, where, like Bush, he was a member of the elite Skull and Bones student society. Kerry, one columnist on The Boston Globe observed, “looks like the kind of guy who wrote a game plan for life when he was still sitting in a sandbox”.

The main thrust of the Republican machine will be to attack Kerry for being wishy-washy and constantly flip-flopping on issues. He initially supported the war in Iraq, for instance, and then opposed it. Kerry’s supporters point to his having sat for nearly two decades on the Senate foreign-relations committee and play up his considerable expertise in complex foreign affairs and matters of military policy. But already the Republicans are picking over his voting record on controversial domestic issues such as gun control (for), abortion rights (pro-choice), civil unions for gay couples (for) and the death penalty (against).

“God, guns and gays is terrain the Republicans are comfortable fighting on,” said one Democrat strategist. “The Senate is an institution that cuts the baby in half constantly… It is often about compromise, and presidential campaigns are not best fought over nuance.”

Kerry’s record as a decorated war hero in Vietnam is powerful ammunition against accusations of weakness. No opportunity is lost to recount his exploits as a US Navy “swift boat” captain, who set out to ferry troops up and down the Mekong delta under enemy fire, after blasting out tracks from the Stones and Jimi Hendrix to fire up his men. Kerry was wounded three times in four months and eventually sent home. But not before being decorated twice for valour. Once for saving a man’s life by pulling him from the river as both were being fired upon. The second time, when Kerry’s boat came under fire from a Vietcong rocket-propelled grenade launcher, he turned the boat towards the river bank, rammed it ashore and pursued the attacker on foot. It was a move so bold, his commanding officer later admitted he wasn’t sure whether to court-martial Kerry or award him the Silver Star. As to his change of heart over Iraq, it reflects the change in attitude of many Americans who initially supported the conflict and now regard it as folly.

But it is in addressing Kerry’s stiff and aloof image that his campaign team faces perhaps its biggest challenge, and it is here that his wife comes into her own. Accusations that there is an element of the “Gore bore factor” about Kerry — referring to Al Gore’s lacklustre campaign for the presidency four years ago — are becoming more frequent. Unlike John Edwards, his charismatic erstwhile contender for the Democratic nomination, Kerry has a tendency to deliver long, convoluted speeches in a dull monotone.

In the last public debate between the two in New York, before the smooth southerner pulled out of the race, Edwards was asked if Kerry had “enough Elvis to beat George Bush”. With one eye on his chances of being picked as a running mate, he deftly sidestepped the question. One Democrat loyalist listening to Heinz Kerry speak in Connecticut a few hours later observed that her husband was “less Elvis, more Leonard Bernstein — I could see him conducting the New York Philharmonic Orchestra”. It was meant, of course, as a compliment. But it is just the sort of comment that could swing wavering voters in Missouri or Michigan back in the direction of a president who professes to spend his spare time cutting back brushwood with a chain saw on his ranch in Texas.

To counter perceptions of Kerry as a refined, patrician figure with a long face and pinched smile, one of the early tactics adopted by his campaign team was to play up the daredevil side to his character. Frequent references were made to his love of motorbikes and sports like windsurfing and kite-surfing. His new advisers have, however, apparently forbidden him from straddling a Harley-Davidson at every opportunity and are trying to play up his softer side. This is where his family comes in. His daughters from his first marriage — Vanessa, 27, a Harvard medical student, and Alexandra, 30, a trainee film director — have been drafted in to talk about their “goofy dad”, who used to embarrass them in public with impersonations of Monty Python “silly walks”. They even told one audience about the time he performed heart massage on their pet hamster after it fell overboard in a cage while being transported on a family holiday.

But it is Teresa Heinz Kerry who is regarded as his trump card in this respect. Although aides accompanying her on the campaign trail look constantly pained in anticipation of another unfortunate comment, Heinz Kerry appears to be tempering her outbursts and channelling her energies into winning over voters. She still has a tendency to talk on the stump about herself and her own pet projects, only promoting Kerry in passing. But unlike the uncomfortably staged kisses between Gore and his wife, Tipper, for the cameras, it is clear that Heinz Kerry adores her husband. For instance, it did him no harm at all when she confessed she would be quite content to be stranded for some time with Kerry “in a foxhole”. He, in turn, describes her as “nurturing and incredibly loving, fun, zany and witty, definitely sexy. Very earthy. European”.

“While many Americans feel uncomfortable talking about their bodies, for instance, Teresa is very direct,” says one close aide. “She will talk openly about any bodily function. Sometimes talking to her is like undergoing a full medical examination.”

At first, Heinz Kerry admits, she was hesitant about her husband’s plans to run for president, aware of the heavy personal toll it would take. But, after long walks alone in the mountains of Idaho, she relented: “The last thing I want is someone to say, ‘You blew it for John.'” And when rumours surfaced earlier this year on the internet’s Drudge Report about the senator having had an affair several years ago with an intern — hastily denied by both Kerry and the woman concerned — Heinz Kerry leapt to his defence. “That Drudge. He’s such a smudge,” she said. There was nothing resembling the comment she had made years before that if she caught her then husband, John Heinz, cheating on her, she would “maim him”.

If you adopt the view that a spouse offers some sort of Freudian window into her husband’s inner character, Kerry’s choice of partner could be seen as a sign of emotional strength, a sign that he is comfortable with strong, outspoken personalities — in stark contrast to Bush, who once asked his wife what she thought was wrong with a speech and apparently drove the family car through the garage door when she told him.

“Among the major questions that get raised about Kerry over and over again are his coolness, aloofness, distance,” says Norm Ornstein, a political analyst with the American Enterprise Institute. “I think Teresa humanises him. He didn’t marry someone who is cool and aloof. Those are not terms you could ever apply to Teresa. She is extremely lively and colourful. A person with views of her own.”

Just how Heinz Kerry will play in middle America, however, is uncertain. There are those who still believe that a prospective first lady, like children, should be seen and not heard. At the same time as stressing that “the model of first lady as someone who puts on white gloves and gardens” has long gone, even Democratic supporters concede that lessons have to be learnt from the way Hillary Clinton deeply divided public opinion by involving herself with policy issues. From the outset she promised the country they would be getting “two for the price of one” in the White House. By contrast, Heinz Kerry admits she is bound to have influence over her husband by virtue of the fact they share the same dining table and bed. But if her husband makes it to the Oval Office, she says, she intends to go back to her work at the Heinz philanthropies.

“Teresa would be a breath of fresh air as first lady,” says Wren Wirth, wife of a former senator and one of Heinz Kerry’s tight circle of longtime female friends, sometimes referred to as the Ya-Ya Sisterhood. “She is cultured, sophisticated, has lived on three continents and is, above all, wise.”

While Pat Nixon played the long-suffering partner, Rosalind Carter the good southern wife, Nancy Reagan brought Hollywood (and mediums) to Washington and Barbara Bush became the nation’s favourite matron, Heinz Kerry would bring back some of the glamour of Jackie Kennedy, it is said. And lend the east wing of the White House more of a global air. “She may inhabit a world that very few do.

But she knows about the haves and have-nots of this world,” says another member of the sisterhood. “She has a compassion that comes from the losses she has suffered. She has got out there and done something in the world, not sat around clipping stock coupons.” Although she has been lampooned for her taste for Chanel and cashmere scarves, her friends paint a picture of her recycling jam jars and taking the remains of food and flowers with her as she moves between her various homes.

Most Americans do not have a chip on their shoulders about the wealth of others, in the way that those in more class-bound European societies do, some argue. What matters, they stress, is not the size of Heinz Kerry’s fortune but what she has done with the money she has. It remains to be seen if the struggling swing voters, whose sympathy she needs to help her husband win over, will feel the same way.

Until recently, Heinz Kerry’s appearances were geared to audiences where Democrats were having simply to decide whether to put her husband or Edwards on the ticket. Met by the sort of welcoming crowd she encountered in Fairfield, Connecticut — where street posters advertise the Architectural Digest and home deliveries of Atkins-diet meals — there was little doubt she felt more comfortable. “I feel very shy when I feel such warmth and adulation,” she began her address there. Her reception in a run-down neighbourhood of New York the following morning was a different matter.

The rows of pensioners lined up to listen to her at the Rain senior citizens’ centre in the Bronx sat stony-faced and grumbling that their exercise class had been cancelled as they waited for over an hour for her to arrive to speak to them. Few seemed to even know who she was, except for one elderly woman who sat grimly clutching her handbag. “I hear she’s loaded,” she sniffed. “What does she know about the lives we lead?”

After being introduced to the largely Hispanic crowd as Madam First Lady, Heinz Kerry began her short address in Spanish as a table of old boys continued clicking their dominoes at the back. “Soy la mama de todos. Me llaman Mama T [I am everyone’s mother. They call me Mama T],” she began uneasily as the pensioners sat in silence. “John will work very hard for you.

“He has been a fighter always,” she continued. Silence. “I promise you if he gets to the White House the American people will be No 1 and the people of the world will be No 2.” Hesitant clapping. “We will make our country dream again. We promise a campaign of hope. We are going to be above the fray, no dirty politics, just work hard,” she concluded to, finally, applause.

“I guess what matters is what you have in your heart, not your bank account,” said 75-year-old Roy Parson, a retired plumber sitting in the back row, as Mama T was whisked away to another event. John Kerry can only hope that voters in the Midwest will reach the same conclusion.