December 16, 2007

December 16, 2007

Investigation

The Argentinians have a new president: the first lady has been voted into her husband’s shoes. But the combative, collagen-enhanced champion of the underprivileged they call Queen Cristina has some dirty laundry that she would rather not air in public. Christine Toomey investigates

At first it was just a ripple of sound. Old songs of resistance to the military juntas rehearsed by a middle-aged huddle in an expectant crowd. But as election results filtered into the ballroom of a grand Buenos Aires hotel confirming Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner as Argentina’s first democratically elected woman president, a wave of nostalgia was unleashed.

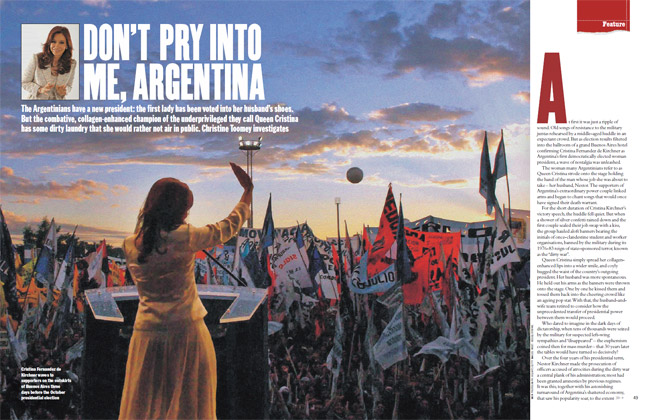

The woman many Argentinians refer to as Queen Cristina strode onto the stage holding the hand of the man whose job she was about to take – her husband, Nestor. The supporters of Argentina’s extraordinary power couple linked arms and began to chant songs that would once have signed their death warrant.

For the short duration of Cristina Kirchner’s victory speech, the huddle fell quiet. But when a shower of silver confetti rained down and the first couple sealed their job swap with a kiss, the group hauled aloft banners bearing the initials of once-clandestine student and worker organisations, banned by the military during its 1976-83 reign of state-sponsored terror, known as the “dirty war”.

Queen Cristina simply spread her collagen-enhanced lips into a wider smile, and coyly hugged the waist of the country’s outgoing president. Her husband was more spontaneous. He held out his arms as the banners were thrown onto the stage. One by one he kissed them and tossed them back into the cheering crowd like an ageing pop star. With that, the husband-and-wife team retired to consider how the unprecedented transfer of presidential power between them would proceed.

Who dared to imagine in the dark days of dictatorship, when tens of thousands were seized by the military for suspected left-wing sympathies and “disappeared” – the euphemism coined then for mass murder – that 30 years later the tables would have turned so decisively?

Over the four years of his presidential term, Nestor Kirchner made the prosecution of officers accused of atrocities during the dirty war a central plank of his administration; most had been granted amnesties by previous regimes.

It was this, together with his astonishing turnaround of Argentina’s shattered economy, that saw his popularity soar, to the extent that his wife has been able to take the reins of power virtually unchallenged. Following in the footsteps of her heroine Eva Peron, Cristina has capitalised on her husband’s success by promising to better the lot of the poor: Evita’s so-called “shirtless” ones. It is largely because voters believe she will continue with Nestor’s economic policies that they voted for her.

But as a veteran lawyer and politician in her own right, Cristina, 54, has vowed to continue with the prosecutions of the military, many of whom are due to go on trial in the next 12 months. One of her most emotive campaign clips featured a message of support by one of the country’s most prominent human-rights campaigners, Estela de Carlotto. She is head of the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, who so many years after the fall of the dictatorship are still searching for grandchildren stolen by the military. But some watched the video with a great deal of circumspection. Both Cristina and Nestor, they point out, prefer to draw a veil over much of their time in the coastal city of La Plata, where they met as students during the dictatorship. A hotbed of left-wing activism, La Plata was a place of mass arrests and widespread disappearances in the 1970s and early ’80s. In the aftermath of the military crackdown, the couple fled to the country’s remote Patagonian province of Santa Cruz for refuge. Few blame them for fleeing such a place of slaughter. But what they did in the frozen far south in the years that followed has invited intense criticism.

In the days leading up to the poll, Cristina declared she did not want to be identified with either Eva Peron or Hillary Clinton – a more obvious modern comparison, given that both women are lawyers, and both met and married men who became provincial governors and then presidents. She was being disingenuous. She has ruthlessly exploited the images of both women to help propel herself to power.

During a battle to secure a Senate seat for Buenos Aires several years ago, she said that, were Evita still alive, the wife of Argentina’s former strongman Juan Peron would undoubtedly vote for her. Like her, Cristina has a love of glamour, albeit with a modern twist. Her closest rival in the presidential race, Elisa Carrio, a staunch anti-corruption campaigner, dubbed her the “Botox queen” and derided her penchant for heavy make-up, hair extensions, stilettos and tight-fitting leather jackets. Also like Evita, Cristina favours fist-shaking when she speaks and, on the rare occasions when she ventures into the country’s most desperate barrios, whips up the crowd with similar friend-of-the-poor rhetoric.

Unlike Evita, however, Cristina had a much more privileged upbringing. The eldest daughter of middle-class parents in La Plata, she is remembered by friends as more focused on her studies than student politics at a time when the country’s youth was ablaze with indignation at social injustice. She did become a member of a Peronist youth movement strongly opposed to the military, as did her future husband. But when their friends began to disappear, they abandoned politics and fled to Patagonia.

There are skeletons in the cupboard from the time they spent in Santa Cruz, where Nestor Kirchner was elected governor three times and she was returned to the national Senate twice. Questions still persist about millions of dollars in oil royalties that the federal government paid to the province of Santa Cruz during Nestor’s time as governor, which he had transferred to secret bank accounts in Switzerland and Luxembourg, allegedly to protect them from devaluation during the country’s financial collapse of 2001-2. Some of these funds, many believe, are still unaccounted for.

Reminders of these transactions surfaced in the capital when Cristina’s election posters were defaced. After part of her campaign slogan – roughly translated as “We know what’s missing” – opponents had scrawled: “The missing millions from Santa Cruz”.

More recently, Nestor Kirchner’s presidency was marred by a series of corruption scandals.

In July his economic minister, Felisa Miceli, resigned after a bag containing an alleged US$240,000 in cash (Miceli claims it was just $60,000) was discovered in the bathroom of her government office. A month later, a Venezuelan businessman was arrested trying to smuggle $800,000 into the country aboard a jet chartered by Argentina’s state energy company. Two Argentine government officials and three executives from Venezuela’s state-owned oil company were travelling with him. The discovery led opponents of the Kirchners to file criminal charges of money-laundering and bribery against the energy companies involved, amid heavy speculation that Venezuela’s president, Hugo Chavez, who shares much of the Kirchners’ left-wing ideology, was smuggling in funds to boost Cristina’s election campaign. A slew of other alleged corruption scandals involving kickbacks to contractors of state-owned companies are also under investigation.

More troubling for many, however, is the source of the Kirchners’ considerable personal fortune from their activities as young property lawyers in the capital of Santa Cruz, Rio Gallegos, during the dirty war. When the military imposed severe financial penalties on those struggling with debt, many lost their homes to repossession. The Kirchners bought more than a dozen of these properties at knockdown prices, allegedly in association with a financial company backed by members of the military. This became the foundation of their small property empire.

“What they did may have been legal. But in the eyes of most it was morally repugnant. It makes a mockery of their claims to have been champions of social justice in their youth,” says Marcelo Lopez Masia, a journalist who spent years working on a documentary about the Kirchners’ activities only to find that no television network would air it. Media outlets critical of the Kirchners in the past have had big advertisers withdrawing their accounts.

The Kirchners’ contempt for the media is well known. Throughout Nestor’s four years in office he never held press conferences and rarely granted interviews. “Cristina is a very strong character. She is much more cold and distant than her husband. She is a woman people either love or hate. She is not someone anyone is indifferent to,” says one of Argentina’s top political analysts, Joaquin Morales Sola, who was granted a rare interview after her election.

Cristina is fond of pointing out that when her husband was elected president, in 2003, it was she who was the better-known politician. As a senator, her finger-jabbing during congressional sessions was legendary. One of her best-known outbursts came in 2003 when she pounded her Senate desk and demanded the High Court repeal amnesties for officials accused of crimes during the dictatorship. The High Court took heed. The amnesty was annulled and the way cleared for scores of prosecutions to proceed.

But opponents view the Kirchners as opportunists who seized the cause of human rights to improve their popularity, concluding that the couple had shown little interest in such causes until they had presidential ambitions. Andrew Graham-Yooll, longtime editor of the English-language Buenos Aires Herald and author of a searing personal account of the dirty war, shares this view. After years as an informant for Amnesty International, Graham-Yooll brought his family briefly to the UK following a period of arrest by the military. “I think they latched onto a very good wheeze, which has less to do with human rights and more to do with using history as a form of revenge,” he says. “I am delighted that a woman has been elected president. I think it is a good sock on the nose for the machistas – macho men – of this country. But questions need to be asked about how much money the Kirchners have salted away and how Cristina abused the apparatus of the state to get elected.” The way she used privileges, such as her husband’s presidential jet and helicopter on the campaign trail, incensed other contenders, who also said many of their potential donors were threatened with punitive tax audits.

For those who have battled for decades for justice for the disappearance and murder of their loved ones, the criticism that the Kirchners are now pursuing the military to polish their image is academic. “The fact is they are doing it, and that is all that matters,” says Estela de Carlotto. “Many of the trials have been going very slowly and Cristina has promised to speed them up. She is a woman and we support her because of that.” Cristina is not the first woman to be elected to political power in Latin America. Last year, Chile elected Michelle Bachelet president. She promptly filled half her cabinet with women. Increasingly, voters in the region seem eager for women to replace traditional politicians associated with the problems of the past. Yet throughout her campaign, Cristina assiduously avoided playing the gender card and, unlike some other prominent female politicians, has kept her two children – Maximo, 30, and Florencia, 16 – out of the spotlight. Once elected, she did profess to feel an “immense responsibility for her gender”, calling on her “sisters” to support her in the great task of government. But days later, she disappointed many of the more liberal-minded by stating that she was opposed to abortion and couldn’t believe “anyone could be in favour of it”.

However, it is not the country’s chattering classes who voted her into power. She found little support at the polls in cosmopolitan Buenos Aires and other urban centres. Most of the country’s middle class sneer at her haughty manner and tacky personal style. But since the collapse of the Argentine economy in 2001-2, which wiped more than two-thirds off the value of most private savings, the ranks of the middle class have shrunk dramatically. For the country’s poor who propelled Cristina to the presidency, only one thing matters: the state of the economy.

In the rain-soaked central market of La Matanza, a sprawling satellite west of Buenos Aires where some of the capital’s poorest scratch a living, Cristina stepped onto a hastily erected stage in a cream silk suit three days before being elected and spoke about “recovering the dignity” of Argentina. “We want the decisions about our country to be made here, not in the offices of the IMF,” she thundered to rapturous applause. Her speech lasted little more than 10 minutes before she was whisked back to the first couple’s official residence in a presidential helicopter. It was the close of a campaign that many regarded as more like a coronation than an election. But it hit the right buttons with the bedraggled crowd. “At least I have work now, and some hope that my children will be educated,” said Eduardo Rivas. A variety of government job-creation schemes introduced over the past four years under Nestor Kirchner have helped cut unemployment from a 2002 high of 21.5% to around 10.4%.

“We want Cristina to follow in the footsteps of Chavez. We want more big changes in this country,” said Paciano Ocampo, 46, referring to the Venezuelan president’s nationalisation of vast sectors of the economy to fund a range of initiatives to help the poor. In recent years, Chavez has also used his country’s oil wealth to bankroll Argentina to the tune of US$3 billion in government bonds to help the country restructure its debt. It is part of a wider strategy to extend his influence in the region.

Like Venezuela, Argentina has been busy nationalising energy and utility companies, allowing the government to freeze prices and keep inflation low. This, together with favourable financial markets and high prices for Argentina’s agricultural products, has helped fuel an annual economic growth rate of 8% for the past four years and saw Nestor Kirchner’s approval rating soar to above 70%. But the government has been plagued by allegations that it has suppressed true economic figures – crucially that of inflation, officially pegged at around 10%, though widely believed to be twice that.

As the global economy worsens, years of underinvestment in Argentine industry threaten to plunge the country into a new energy crisis. This means the future looks far less rosy for Cristina’s presidency. Some believe this will play into her husband’s hands. “It is clear now why Kirchner appointed his wife candidate. It is clear her period of government will be more difficult than his and he is happy for her to pay the price for this. In some way, he is sacrificing her for his own political ambition,” argues Rosendo Fraga, a veteran observer of the country’s political scene. “Kirchner doesn’t want his wife to fail, because that would bring him down too. But he doesn’t want her to be too successful, either. That will leave the way open for him to be re-elected in four years as the one-time saviour of his country. Cristina and Kirchner are politicians first, husband and wife second. As with all such alliances, politics, power and ambition come before marriage.” Aides point to differences between the pair. Cristina is viewed as more of a negotiator. And where Nestor showed no interest in foreign policy, his wife is expected to devote much of her time to the diplomatic circuit. In the few months of her campaign, she spent more time visiting foreign leaders than travelling around Argentina wooing voters. Detractors derided much of this travel as extended shopping trips. But for a country desperate for foreign investment, such excursions are crucial.

On the trickier matters of international diplomacy, she has remained silent. Little was said when, shortly before the election, Britain confirmed its intention to file a claim to 386,000 square miles of oil- and gas-rich South Atlantic sea bed. Argentina and Chile also claim sovereignty over the area, extending out from British Antarctic Territory.

Under the 1959 Antarctic treaty and subsequent protocols, any attempt at mining and drilling in the area is banned for at least the next 40 years. But shrinking Middle East reserves make exploitation increasingly tempting.

Given the lingering bitterness over the Falklands war, such a muted response from Cristina surprised some, especially since the Kirchners’ traditional power base is in the southernmost tip of the country, closest to Antarctica. Cristina sometimes calls herself La Pinguina – The Lady Penguin – after the inhabitants of those southern reaches. Her husband was similarly nicknamed Penguin because of his southern roots and prominent nose. Analysts say they are now imitating the role-reversal behaviour of emperor penguins, who send the female out to sea in search of food while the male stays back to incubate their egg.

Asked what her husband would do after he slipped the presidential sash over her shoulders, however, Cristina joked that she does not trust him to stay at home. “He’ll do what he has always done,” she says. “He’s a political animal.” Whether this means he will continue to pull the country’s political strings behind the scenes, or if Argentina’s first couple intend to take turns passing the reins of power between them, as emperor penguins do with their chicks, remains to be seen.