March 30, 2008

March 30, 2008

Investigation

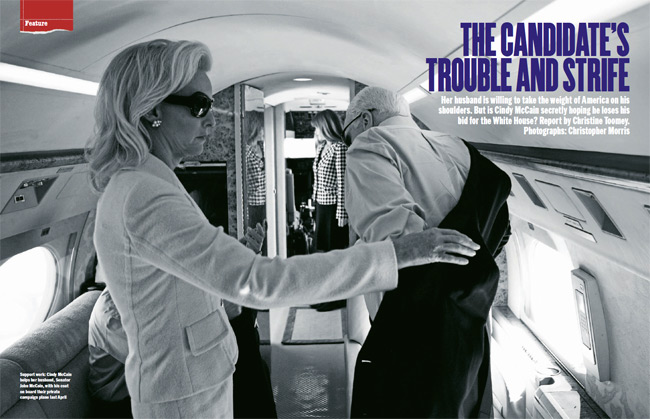

Her husband is willing to take the weight of America on his shoulders. But is Cindy McCain secretly hoping he loses his bid for the White House?

Phoenix, Arizona. On the stretch of street where Cindy McCain grew up and, in the same house, raised her own family with the Republican presidential candidate Senator John McCain, tall, toned women in tight-fitting shorts jog along the sidewalk in the sunshine. Across the lawns of the spacious homes that trail away on either side, gardeners, mostly Mexicans, stoop low, snipping hedges and tending swimming pools.

The social lives of wives and mothers here revolve around husbands, children, pot-luck dinners and block parties. One has set up an e-mail alert system in the event of rare winter frosts in this desert-city suburb, so that neighbours can quickly pull protective covers over treasured flowers. But against this backdrop of pampered privilege, all is not necessarily what it seems. Family dramas are laundered in private, and rarely stain the manicured lives of neighbours – unless, that is, a husband decides to make a run for the White House. Then the world intrudes, poking its nose into the nooks and crannies of respectability in search of the sleepless nights endured in pursuit of such ambition.

Friends and neighbours close ranks around their own, throwing up stone walls to intrusive questions, questions that won’t go away about Cindy McCain and her life at 7110 North Central Avenue. They present an impenetrable and united front to protect the woman who may be America’s next first lady.

To flank it, and to understand the long and sometimes deeply troubled road that Cindy McCain has travelled to stand by her husband, immaculately dressed and accessorised with a pearly white smile, we need to return to a different era, to a time when America was not tarnished in the eyes of the world, to the star-spangled days of the American dream, when JFK was in the White House; a time when Cindy McCain was just a clever, beautiful girl known in the neighbourhood as Cindy Lou.

) ) ) ) )

In a society as transient as the United States, where the average family stays only five years in one home before moving on, the North Central Avenue area is unusual. For a street so close to the bustling office blocks of downtown Phoenix, one of the fastest-growing cities in the country, it has a strangely suburban feel. Originally an orange grove where developers built ranch-style homes so “upper-income residents” could keep horses, it still has a gravel bridle path running the length of the street. Families who live here tend not to move on quickly. So there are some here who still remember Cindy Lou as a girl.

Behind 7110 North Central Avenue, where she grew up, one elderly couple, John and Sally Auther, have lived in the same house for 50 years. They still recall Cindy Lou. “Her folks were somewhat protective of her. She was not a real outgoing type. She didn’t mix a lot with other kids in the neighbourhood when she was young; neither did her own children,” says Sally Auther.

One point on which everyone agrees is that Cindy Lou was the apple of her father’s eye. Born in 1954, she was the only child of Jim Hensley and his wife, Marguerite, known as “Smitty”. While Smitty was strict and reserved, Jim doted on his daughter and gave her the best of the privileged lifestyle the couple had earned. Neither came from wealthy backgrounds. They met in St Louis after the second world war and moved to Phoenix, borrowing $12,500 to buy the licence for a beer-distribution company. “Selling beer in the desert was a gold mine. They did pretty well for themselves,” Auther recalls. It’s an understatement. Hensley & Company, the third largest wholesaler of Anheuser-Busch beer in the US, is now a $300m-a-year business (which Cindy McCain took over when her father died in 2000). Even when she was growing up it was a thriving business. The Hensleys kept clydesdale horses, the large Budweiser mascot breed. Jim Hensley liked to ride and, when his daughter was old enough, he took her on long treks through Arizona to California and Mexico.

At 14, Cindy Lou was crowned the local rodeo queen. At 15, she transferred to Central High School in Phoenix – its motto was “America’s high school”. The retired principal, Cindy Lou’s former teacher David Silcox, explains. “It represented all that was good about America: opportunity for all, contributing to the common good, giving something back if you’ve been given gifts by birth. All that might sound a bit hokey, apple pie and hot dogs,” he says. “But it’s what we believed, and I still do.”

By the time Cindy Lou arrived at Central High in 1969, however, storm clouds had already darkened the American dream. JFK had been assassinated; his brother Bobby too. The civil-rights movement had been devastated by the murder of Martin Luther King Jr, and Richard Nixon was in the White House, sinking into the quagmire of the Vietnam war. But the only mention of that faraway conflict in the school yearbook of her freshman year is a reference to a “candy apple and chewing gum sale” held to raise money for children in South Vietnam. The book challenges students to follow the American poet Carl Sandburg’s plea “to gain recognition… have our faces noticed… [even though] such a position may not at all times be comfortable… Faces speak what words can never say”. These are poignant words now; Cindy McCain’s body language, as she stands smiling by her man on the campaign trail, sometimes suggests she is not happy at the idea of moving permanently into the limelight.

In high school, Silcox remembers Cindy Lou as “a motivated, diligent student, very involved in community-service activities like cleaning up city parks, helping the homeless and the elderly” – an altruistic streak that would thread through her life. While contemporaries recall “a pompom line girl”, a cheerleader, old school newspapers and yearbooks make no mention of this.

“Perhaps she was just a quiet kind of kid,” says Randi Turk, Central High’s dynamic English teacher, as together we leaf through the yearbook of her senior year. There she is, looking prim in a tailored trouser suit. While other students, shown fooling around in hippie hairbands and floral smocks, were voted “most congenial”, “most respected” and “most talkative”, Cindy Lou was voted “best dressed”. Contemporaries remember that while most girls bought their high-school prom dresses in the local store, her mother took her to Los Angeles to get hers.

By the time she left Central High in 1972, however, Vietnam had intruded. The yearbook is testimony to the generational turmoil the war provoked. It pictures a visiting congressman vowing that no amnesty would be granted to draft-dodgers, while a teacher is quoted as saying: “We’ve become the people that burn children.”

) ) ) ) )

For the four years that Cindy Lou was at Central High, the man who would become her husband was a prisoner of war in Hanoi. John McCain, a naval pilot, was shot down on a bombing mission over North Vietnam in 1967 and tortured so badly during the next 51/2 years in which he was held captive that he attempted suicide before being released after the 1973 Paris peace accords.

By then, Cindy Lou had gone to study education at the University of Southern California (USC), which one American reporter says McCain once quipped stood for “University for Spoiled Children”. But the path his wife chose after graduating with a master’s degree was not that of a brat. Returning to Phoenix, she followed the Central High ethos of “giving something back”, and went to work as a special-needs teacher in one of the poorer neighbourhoods of the city.

“All of a sudden this beautiful blondie shows up on campus and takes us all by surprise,” recalls the former principal of Agua Fria high school in Avondale, 75-year-old “Okay” Fulton. “The kids adored her. She was highly dedicated. She taught teenagers with Down’s syndrome and other disabilities. A lot of their parents were cotton farmers, some extremely poor, and she’d pay home visits to understand the kids’ problems better. She didn’t need to do that, any of it. Her dad had lots of money. But she was dynamic, dedicated, a happy young lady. She became an integral member of our staff.”

After just two years teaching at the school, however, Cindy Lou handed in her notice. On holiday in Honolulu with her parents in 1979 she met John McCain, then a navy liaison officer. Up until then, Cindy says, she had dated “very nice men from college”. But faced with a naval officer in dress whites, whom she describes as “intelligent, witty and thoughtful”, she was smitten. Having had such a strong bond with her father, she admits she wanted an older man. McCain was 18 years older – and married with three children. His first wife, Carol, had been disabled in a car accident while he was held prisoner in Vietnam. But within a year he had divorced Carol and married Cindy.

Realising his military career was never going to reach the heights of that of his father’s or grandfather’s, both naval admirals, McCain had his sights set on success in a different field: politics. With the help of Cindy Lou’s family fortune and Jim Hensley’s powerful contacts in Arizona, McCain moved to Phoenix, within a year was a congressman and, four years after that, a senator for Arizona. He soon developed a reputation as a political maverick – a trump card he is still playing in this presidential campaign with an electorate desperate for change.

But while McCain commuted back and forth to Washington, DC, Cindy refused to move with him. After suffering several miscarriages, she gave birth to three children: Meghan, 23, Jack, 21, and Jimmy, 19. The couple also adopted a daughter, Bridget, now 16. Cindy wanted her family to grow up in the same house with the same roots and values she had. “A lot of the time, what I saw with families [in Washington] was a pecking order among the kids: whose dad or mom did this, and how close they were to the president,” she once said. So instead the McCains spent $250,000 remodelling her parents’ home as a Mexican-style ranch house, which Cindy dubbed “La Bamba”. She went on to found a charity, American Voluntary Medical Team (AVMT) in 1988, to provide mobile medical units to disaster-stricken areas around the world.

It was at this point that Cindy’s life took a dramatic turn. To the outside world the McCains appeared to be a family blessed with good fortune. But behind closed doors, the immaculate Cindy McCain was falling apart.

) ) ) ) )

The reporter I meet for coffee in a quiet corner of a downtown office block in Phoenix is edgy. The McCains have a troubled history with the Phoenix press and he prefers not to be identified. As he tells it, the McCains attempted a classic manipulation of the media to contain the damage caused by the drama that unfolded in Cindy’s life. But the McCains suffered a backlash in the papers as a result, and have had an uneasy relationship with local journalists ever since.

Sympathetic stories were spoon-fed to journalists in 1994. One of them began “she was a rich man’s daughter who became a politically powerful man’s wife. She had it all, including an insidious addiction to drugs that sapped the beauty from her life like a spider on a butterfly”. Cindy McCain, the story went, had “opened a remarkably ugly wound in her life” by admitting that for four years, beginning in 1989, she was addicted to powerful prescription painkillers. The addiction began after surgery to repair four ruptured discs failed to ease the pain. Her addiction was so overwhelming that she admitted locking herself in the bathroom to secretly pop four or five times the prescribed dosage each day, medication obtained from several doctors, each of whom she failed to tell that she was getting prescriptions elsewhere. Eventually she took to stealing the drugs from AVMT. This led to an investigation by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which was tipped off by a disgruntled employee that there was a connection between the charity’s supply shortfall and Cindy McCain’s drug problem.

The addiction was exacerbated by the turmoil surrounding her husband’s involvement in a political scandal known as the Keating Five. In 1991, the US Senate investigated five senators accused of using their influence to protect the financier Charles Keating from a federal probe. Although McCain was later shown to have been among the least culpable of the five, he faced a Senate Ethics Committee investigation. As the family book-keeper, Cindy McCain became embroiled when she failed to produce personal cheques that had been used to repay Keating for the family’s use of the financier’s home in the Caribbean. “I was on the floor. I couldn’t deal with it,” she said at the time, admitting that the scandal strained her marriage.

Confronted by her parents in 1993 about the erratic behaviour that was a result of the drugs she was taking, Cindy said she went cold turkey and never touched the pills again.

A hysterectomy alleviated her back pain. She had managed to hide her addiction from her husband, she says, because he was away so often in Washington, DC. She only told him about it when the DEA came knocking with its investigation into her charity. “It was my secret. It kept building inside me until I was afraid I might burst. It was the darkest period in my life,” she said later. When McCain learnt the truth, he issued the statement: “I have no doubt that the inevitable ups and downs of my political career have been rough on her. She has my love and support and that of her entire family.” Publicly, both say the affair strengthened their marriage.

What did not emerge until after these first softball stories appeared was that the reason the McCains went public – though this was spun at the time as an attempt to help addicts in a similar situation seek treatment – was that the disgruntled former AVMT employee, after being sacked, had approached another Phoenix newspaper with the story of Cindy’s theft of drugs from the charity. That newspaper, the Phoenix New Times, was on the point of printing the story when the McCains called their own press conference to take the heat out of the scandal. The employee, Tom Gosinski, claimed he was fired because he knew too much. The McCains claimed he only went to the press after unsuccessfully trying to blackmail them in return for keeping quiet. But the damage was done: locally the press felt manipulated.

As a result of the DEA investigation, AVMT was closed down, and a doctor who worked for the charity and had filled out prescriptions for Cindy lost his licence to practise medicine, while she went into rehab for a few days and then started attending meetings of Narcotics Anonymous twice a week.

Six years later, when McCain made an unsuccessful bid to become the Republican party’s presidential candidate, the media revisited this story, as it has done again recently. But the 2000 election campaign for the candidacy had even more disturbing consequences for Cindy.

The South Carolina primary that year was described by one of McCain’s advisers as “the dirtiest race I’ve ever seen”. In an attempt to dissuade voters in the Deep South from voting for him, posters were anonymously distributed alleging McCain had fathered an illegitimate black child. George Bush, who went on to win the candidacy and two terms in the White House, was believed by the McCain camp to have been behind the move. The couple were devastated. The posters referred to a baby from an orphanage in Bangladesh whom the McCains had cared for since she was 10 weeks old and later adopted. Personally handed to Cindy by Mother Teresa in 1991 during an AVMT mission in the country, the baby girl suffered from such a severely cleft palate that it was not believed she would survive unless she was taken out of the country for medical treatment.

“I really thought I was politically seasoned, with five or six congressional races under our belts at that point,” Cindy said afterwards. “But I did not have a clue – to involve my daughter was unconscionable. I was blown away by it.”

The prospect of her children being harmed again as a result of such dirty electioneering tactics made Cindy wary of her husband going on the campaign trail again, close friends say. Even she admits: “You can see the toe marks in the sand where I was brought on board. I was reluctant to get involved.” So just what did bring her on board McCain’s campaign?

) ) ) ) )

In a western suburb of Phoenix, I talk to one of Cindy’s closest friends, Sharon Harper, whose family has a weekend cabin adjoining the McCains’s in the red-rock country of Sedona, south of the Grand Canyon.

“Of all the things Cindy will say, No 1 is, ‘I want to be known as a great mother.’

That’s why she’s doing this,” says Harper. “She has two sons in the military now. Her youngest, Jimmy, was in Iraq until two weeks ago. She wants John to be this country’s next commander-in-chief. Not only for the sake of her own children but for every mother and father like her with sons and daughters in harm’s way.” Harper says that while the McCains’s son, a marine, was in Iraq, his mother kept a mobile phone strapped to her wrist so that she would never miss a telephone call from him. “As a mom, she was terrified when he was in Iraq,” says Harper. “She prayed every day and sent gifts.

But she kept it inside. It wasn’t until he came home that she allowed herself to cry.”

In the light of such maternal concern, it’s hard to see what comfort she might take from her husband’s talk of keeping US troops in Iraq for 100 years or more if necessary. The Iraq war is one of the hottest issues in the presidential campaign, and McCain is trading on his harrowing military experience to convince voters that he understands better than anyone what armed conflict is. While his statements on Iraq have caused alarm, as a badly tortured former PoW, his promise to close the controversial Guantanamo Bay detention camp immediately if he becomes president has been widely praised.

But given all the baggage of the Bush White House, he faces an uphill struggle to present himself as a man who will introduce other significant changes. Just how different his economic policies would be from those

of one of the least popular presidents since polling began, and one who has accrued one of the biggest budget deficits in US history, remains unclear. The one area where he does distance himself significantly from Bush is on environmental issues. McCain says he will make tackling climate change a priority, and that he will begin by enforcing legal limits on the emission of greenhouse gases. His children are reported to have pressured him on this when he called a family “summit” with Cindy before deciding to run for president.

Harper, a formidable businesswoman, is suddenly overcome when she contemplates the prospect of the McCains moving to Washington, DC. “To think about Senator McCain becoming president and how that affects his family, how a little girl from Mother Teresa’s orphanage in Bangladesh could end up living in the White House – well, it’s just beautiful,” she sighs.

When I ask where Cindy would find the steel to deal with the pressures of living at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Harper says she believes that having grown up in “early Arizona” would give her the strength of character: “She wasn’t a rancher, but was part of that Old West culture – out in the open, with big skies, riding a horse. That does something to the inside of a person.”

Just four years ago, however, Cindy suffered a stroke, losing both her speech and partial use of the left side of her body. Another friend I speak to says it was because she stopped taking blood-pressure medication. After a period of physical therapy, she is said to have fully recovered and has since taken up her son’s love of “drifting” – a kind of motor racing that involves driving cars sideways – to improve her co-ordination. Speaking of her friend’s stamina, Harper stresses that, in addition to running a multi-million-dollar company, Cindy also still regularly travels to trouble spots all over the world through involvement with charities such as the anti-landmine Halo Trust and Operation Smile, which treats children with facial deformities.

Besides, the question of physical frailty is more of an issue when it comes to John McCain, now 71. If elected, he would be the oldest man to take up the presidency. Harper gamely rises to the challenge of discussing McCain’s age by telling an anecdote about how his 96-year-old mother recently flew to Paris to celebrate her birthday at Maxim’s restaurant and how, on an earlier trip to France, after being refused a rental car because of her advanced years, she went straight out and bought a car. “With those sort of genes, John has enough energy to serve four terms,” she laughs, before, to my mind, defeating her own argument by adding: “Besides, he’d only be a year or two older on entering the White House than the greatest president to have served this country, ever – Ronald Reagan.”

) ) ) ) )

All the time I am in Arizona, I am only too aware that the most compelling drama of this election is going on elsewhere. The week I trudge the streets of Phoenix is the week Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton sit elbow to elbow in Austin, Texas, for a televised debate vying for the Democratic party’s nomination as presidential candidate. The encounter is electrifying. For days afterwards the television and newspapers are full of little else. After winning a series of successive primaries, Obama was generally agreed to have held the edge that night. Hillary had only come to life right at the end, when she was asked how she coped with crisis and answered, with a wry smile, that everyone in the nation knew she had had her “challenging moments” – meaning as first lady married to a philandering president. Less than two weeks later she was being dubbed the “Duracell bunny of US politics” after retaking the momentum, winning primaries in Ohio, Texas and Rhode Island, redrawing the battle lines for a protracted struggle for the nomination. Polls predict that McCain stands a better chance of winning in November if Hillary is chosen as the candidate.

But the same day as the Texas debate, The New York Times carries a report insinuating John McCain had had a romantic relationship with a female lobbyist. An ashen-faced McCain, with sombre-suited Cindy by his side, had called a hasty press conference early in the morning to deny the allegation and condemn the report as a smear campaign. Given the lack of evidence in the article, his complaint was widely held as justified. But there was an eerie echo of Hillary standing by her man as a clearly shaken Cindy stepped up to the microphone and declared: “I not only trust my husband, but know he would never do anything to not only disappoint our family but disappoint the people of America.”

A few nights later, I sit talking with two of Cindy’s contemporaries from Central High. They have generously invited me to dinner, but a steely edge enters the conversation when I bring up the subject of the New York Times report. “That’s such garbage. John and Cindy have a wonderful marriage,” one of my hosts insists, before adding: “We really have to wrap things up quickly now.” They don’t actually ask me to leave, but I get the message. As I gather my things, one of them says: “I hope you’re not going to go writing mean things about our Cindy.”

Granted, Cindy McCain is not standing for office. She has been thrust into the limelight because of her husband’s ambition. But in the event that voters decide next November that McCain’s age and experience outweigh the need for real change, she could find herself in Hillary’s shoes in the East Wing of the White House in January 2009. There she would have her own staff and undoubted influence over the next “leader of the free world”.

When I ask Harper what kind of a first lady Cindy would make, she loyally suggests her friend would combine the “elegance of Jackie Kennedy with the graciousness of Laura Bush. Cindy will be the same person she has always been. She is reserved and shy. But she is good one-on-one with people. She will reach out”.

But as I drive back along the palm-lined avenues of downtown Phoenix and try to imagine the personal wrench it would take for her to leave her lifetime home here for the scrutiny of Washington, DC, I can’t help feeling that in the depths of her soul, Cindy Lou Hensley McCain might privately hope it is a road she won’t have to travel.