February 10, 2008

February 10, 2008

Investigation

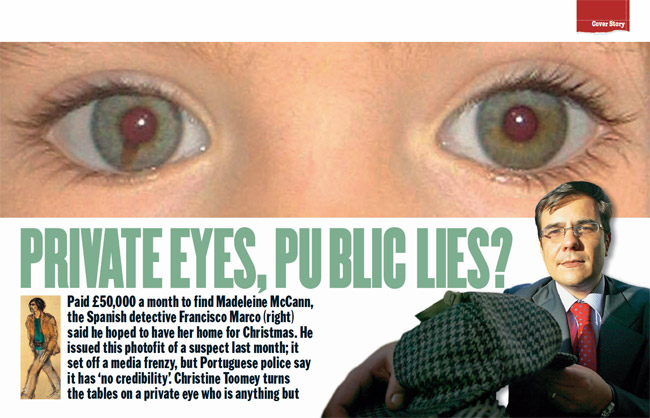

Paid £50,000 a month to find Madeleine McCann, the Spanish detective Francisco Marco said he hoped to have her home for Christmas. He issued this photofit of a suspect last month; it set off a media frenzy, but Portuguese police say it has ‘no credibility’. Christine Toomey turns the tables on a private eye who is anything but

Francisco Marco might have been thinking about other matters on the day he apparently spoke out about his hopes that Madeleine McCann would be home for Christmas. It was the day his Spanish private detective agency, Metodo 3 – paid an estimated £50,000 a month to help find Madeleine – moved from cramped premises above a grocer’s shop specialising in sausages in Barcelona’s commercial district to a multi-million-pound suite of offices in a grand villa on one of the city’s most prestigious boulevards.

When a taxi driver drops me off at Metodo’s new premises, he tilts his finger against the tip of his nose and says “pijo” – meaning stuck-up or snobbish. Pointing to the restaurant on the ground floor, he says: “That’s where people who like to show off go – so others can see their Rolex watches and designer clothes.”

It is in his office on the second floor that Marco has agreed to meet me, the first British journalist, he says, to whom he has ever granted an interview. When I point out that he was filmed by a Panorama documentary crew in November claiming he was “very, very close to finding the kidnapper” of Madeleine, he corrects himself: “Well, apart from that.” Marco will tell me later how who he has spoken to, and what he has or has not said, has been misunderstood.

But first I must wait, taking a seat at a long, highly polished boardroom table surrounded by pristine white-leather chairs. At one end of the room, discreetly lit shelves display an impressive collection of vintage box cameras and binoculars. Stacked against the walls are modern paintings waiting to be hung. It feels more like an art gallery than the hub of one of the most frantic manhunts of modern times.

There is no discernible ringing of telephones; little sign of activity of any kind, other than a woman searching for a lead to take a pet poodle for a walk and the occasional to-ing and fro-ing of workmen putting finishing touches to the sleek remodelling of the office complex.

It is not clear whether this is where the hotlines for any information about Madeleine are answered. Opposite the boardroom is an open-plan area of around half a dozen cubicles, equipped with banks of phones and computers. Most are empty when I arrive; admittedly it is lunch time. But I cannot ask about this.

“We won’t answer any questions about Maddie. Maddie is off limits – is that understood?” Marco’s cousin Jose Luis, another of the agency’s employees, warns me sternly.

Catching me eyeing the setup, he is quick to explain that Metodo 3, or M-3, bought the premises earlier last year. Though I say nothing, I get the distinct impression he wants to make it clear that this was before M-3 persuaded those involved in decisions regarding the £1m Find Madeleine Fund – partially made up of donations from the public and partly from business backers such as Brian Kennedy – to sign a six-figure, six-month contract with the firm, whose financial fortunes now seem assured by the worldwide publicity they’ve since received.

“All the remodelling work took months, so we only moved in on December 14,” he says, hesitating slightly before adding: “Moving is better at Christmas.” The implication that this was a quiet period for M-3 is strange, as it was exactly the time Marco is reported to have said his agency was “hoping, God willing” that Madeleine would be imminently reunited with her family. Marco has since denied he said this.

I cannot ask him to clarify what he did say, or whether talking about an ongoing investigation is potentially detrimental. Instead, I am left to discuss the matter with a handful of other private detective agencies in Barcelona, the private-eye capital of Spain. What they tell me is disturbing.

I expect a certain amount of rivalry, and some of what they say about M-3 could be dismissed as jealous gossip. But they claim otherwise.

They say there is nothing they would like more than to see M-3 succeed in solving the mystery of Madeleine’s disappearance. But they worry that M-3’s inflated claims of progress in the case is making a laughing stock of the rest of them. References to Inspector Clouseau cut deep. They are proud that, unlike their UK counterparts, Spanish private detectives have to be vetted and licensed. They must also have a specialised university degree in private investigation. More importantly, in a profession where discretion is critical, they worry about the effect of such public declarations on the progress of any investigation. It is in the days following reports that the Find Madeleine Fund is considering sacking M-3 that I talk to Marco – though of course I cannot discuss this with him.

Clarence Mitchell, the spokesman for Kate and Gerry McCann, Madeleine’s parents, says he believes M-3 “put themselves forward” for the task, as did a number of other companies. Just a week after the four-year-old’s disappearance from the McCanns’ holiday apartment in Praia da Luz in the Algarve on May 3 last year, Portuguese police had announced that official searches were being wound down. Initially, the British security company Control Risks Group, a firm founded by former SAS men, was called on for advice. Mitchell confirms that the company is still “assisting in an advisory capacity”, but he says that the reason the

Spanish detective agency was hired was because of Portugal’s “language and cultural connection” with Spain. “If we’d had big-booted Brits or, God forbid, Americans, we’d have had doors slammed in our face, and it’s quite likely we could have been charged with hindering the investigation, as technically it’s illegal in Portugal to undertake a secondary investigation,” Mitchell explains. “But because it’s Metodo 3, [Alipio] Ribeiro [national director of Portugal’s Policia Judiciara] is turning a blind eye.” Portuguese police are reported to dismiss M-3 as “small fry”.

Mitchell says the decision to hire M-3 on a six-month contract from September was taken “collectively” by Gerry McCann, and the family’s lawyers and backers, on the grounds that the agency had the manpower, profile and resources to work in several countries. “You can argue now whether it was the right decision or not,” he says, referring to widespread reports that M-3 will find its contract terminated in March – if it hasn’t been already – and not just because the Find Madeleine Fund is dwindling. “But operationally Metodo 3 are good on the ground,” he insists.

It was M-3, for instance, who recently commissioned a police artist to draw a sketch of the man they believe could be involved in Madeleine’s disappearance, despite Portuguese-police claims that the sketch had “no credibility”.

Clearly, the McCanns are desperate to keep Madeleine’s disappearance in the public eye. And the release of photofits by M-3 will help to achieve this. The McCanns insist, however, that they are not engaged in a bidding war for interviews with American television.

But when 35-year-old Marco finally breezes into his company boardroom and throws himself into a chair opposite me, I do not get the impression that the prospect of losing the contract that has brought his company such notoriety is playing much on his mind.

Marco slaps on the table a 144-page pre-prepared dossier of articles written in the Spanish press about himself and M-3. He goes on to list some of those in the city he says I have already been speaking to about his company. Had my movements been monitored? If so, why would a private detective agency be interested in this at a time when they were supposed to be tirelessly searching for the most famous missing child in the world? This confounds me until, after talking to Marco for half an hour, I conclude that what motivates him – as much as, if not more than, his professed desire to present Madeleine with the doll he boasts he carries around in his briefcase to hand to her when he finds her – is a sense of self-regard, self-publicity and money.

) ) ) ) )

In most of the many pictures of himself included in the material he hands me, Marco looks a little nerdy. He wears the same serious expression, slightly askew glasses and suit and tie in nearly all of them. But when we meet he has a more debonair look. He is wearing a black polo-neck jumper underneath a sports jacket, sharper, and better-adjusted half-rimmed glasses, and a fringe that looks as though it has been blow-dried. It is as if his image of how a suave private eye should be has finally been realised.

In contrast to the other private eyes I meet, however, Marco is anything but relaxed. While most of them sit back easily in their chairs, trying to size me up, Marco leans towards me as we talk. He presses his hands hard on the table, almost in a prayer position, to emphasise a point, and has an intense, slightly unnerving stare.

He seems eager to please. He summons a female assistant on several occasions to bring me material, including a book he has recently written, to illustrate what he is talking about. Even when I make it clear this is not necessary – aware that these distractions eat into the time we have to talk – he insists, partly showing off.

When I ask about his background, Marco summons her to photocopy the first pages of his doctoral thesis on private investigation: he has a master’s degree and a PhD in penal law. He gets strangely agitated when she can’t find it, telling her to carry on looking, then mutters that he will have to look for it himself. Eventually he starts to reminisce about his youth. As a teenager, Marco says, he was so keen to become a private detective that he would get up at 5am to follow people on his scooter and record their movements before starting and after finishing his studies. His mother, Maria “Marita” Fernandez Lado, founded M-3 in 1986, when he was a boy, and he used to help out in the agency every holiday.

I hear several different accounts of what Marita was doing before she set up the agency. According to her son, she was working on a fashion magazine when, by chance, through Marco and his brother’s boyhood love of sailing, she met and became friends with a private detective. “From that moment, she decided she wanted to create her own detective agency, and wanted it to be a big company with big cases, a real business. She wanted to change the public image of a small private detective concerned with infidelities,” Marco says.

In Spain, private eyes are sometimes called huelebraguetas – “fly [zip] sniffers”. One of the reasons Barcelona has always been the home of so many of them, Marco explains, is that Catalonia – traditionally one of the wealthiest regions in Spain – had many rich families wanting to safeguard their inheritance. So parents would employ “fly sniffers” to check out the backgrounds of the people their sons or daughters wanted to marry. M-3 took a different track. It started specialising in investigating financial swindles, industrial espionage and insurance fraud. His mother was the first private detective, Marco says, to provide video evidence used in court to unmask an insurance fraudster: she filmed a man reading who had claimed to be blind. Marco also speaks about how in the early 1990s his mother had helped advise the Barcelona police, who were setting up a new department dedicated to investigating gambling and the welfare of children. He says his mother advised them on how to track adolescents who had run away from home, helping them to trace 15 or 16 of them at that time. (It is when I try to bring the interview back to this subject, to see if these were the children the agency has talked about finding in the past, that the interview grinds to a halt.)

But the agency almost came to grief early on, when police raided its offices, and Marco, his mother, father and brother were arrested and briefly jailed in 1995 on charges of phone-tapping and attempting to sell taped conversations. They were never prosecuted, as it was clear that the police had entrapped them.

Their big break came nearly 10 years later, when M-3 was credited with tracking down one of Spain’s most-infamous spies, Francisco Paesa, a notorious arms dealer and double agent also known as “El Zorro” (The Fox) and “the man with a thousand faces”. Paesa fled Spain after being charged with money-laundering. His family claimed he died in Thailand in 1998 and arranged for Gregorian masses to be sung for his soul for a month at a Cistercian monastery in northern Spain. Acting for a client who claimed to have been defrauded by Paesa’s niece, M-3 traced the fugitive to Luxembourg. At the behest of the Spanish national newspaper El Mundo, the agency then traced him to Paris. Paesa remains on the run, however.

“This was just one of our great achievements. Our biggest successes have never been made public,” boasts Marco. “If you speak to other detectives in Spain, I don’t think they will speak very highly of us because they are envious. But as far as other detectives around the world are concerned, we are the biggest, the most famous; the ones who work well.”

Again in collaboration with El Mundo, and again by following an illegal money trail, M-3 last year tracked down the daughter of the wanted Nazi war criminal Aribert Heim to a farm in Chile. “This was pro-bono work, and we only do it when we have time,” says Marco. The hard-pressed detective did have time just before Christmas, however, to launch a book he had co-written with a Spanish journalist. The book claims that clients of M-3 sacked directors of a charity involved in sponsoring children in the Third World, were victims of a plot to discredit them by people associated with a Spanish branch of Oxfam who were jealous that the public was giving them large donations. The sacked directors are still under investigation for fraud.

It is perhaps because Marco has spent so much time collaborating with journalists in the past that he feels so comfortable talking to the press – the Spanish press, at least – about his investigation into Madeleine McCann. In November he gave two lengthy interviews about the case, one to El Mundo and another to a Barcelona newspaper, La Vanguardia.

In the interview with El Mundo, Marco talks touchingly about how his six-year-old son asks him the same question every evening when he kisses him goodnight: “Papa, have you found Maddie?” Because the little boy is learning to read, the article continues, he knows that his father is “the most famous detective in the world”.

But why, the journalist Juan Carlos de la Cal asks, would anyone in the UK, “the country of Sherlock Holmes, with all its cold-war spies and one of the most reliable secret services in the world”, have chosen M-3 to help? “Because we were the only ones who proposed a coherent hypothesis about the disappearance of their daughter,” Marco replies, explaining that M-3’s “principal line of enquiry” at that time – the article was published on November 25 – was “paedophiles”. He talks about how he “cried with rage” when he investigated on the internet how paedophiles operate.

Apart from these comments made by Marco, little concrete is known about how M-3 has been conducting its investigation. In the same article, Marco’s mother says the agency, which she claims has located 23 missing children in the past, has “20 or so” people working exclusively on the McCann case. M-3 was said at that time to be receiving an average of 100 calls a day “from the four quarters of the globe”, and to have half a dozen translators answering them in different languages. The agency has distributed posters worldwide bearing Madeleine’s picture with the telephone number of a dedicated hotline it has set up to receive tip-offs. The interview was carried out just after Marco returned from a two-week trip to Morocco, a country he describes as being known for child-trafficking and a “perfect” place to hide a stolen child. The north receives Spanish TV, he says, but the rest of Morocco knows nothing about the affair.

Yet in an interview published three weeks earlier in the newspaper La Vanguardia, Marco claimed that the agency had “around 40 people, here and in Morocco” working on the case, on the hypothesis that the child was smuggled out of Portugal, via the Spanish port of Tarifa, to Morocco, “where a blonde girl like Madeleine would be considered a status symbol”. At that time he said he didn’t want to think about paedophilia being involved. Asked how often his agency contacts the McCanns with updates, Marco replies “daily”. He adds that the fee that M-3 is charging for its services is not high. He says that it is “symbolic”.

In the same article – accompanied by a photograph of Marco holding a Sherlock Holmes-style hat – he says with absolute certainty that Madeleine is alive. “If I didn’t think she was alive, I wouldn’t be looking for her!” At first he states categorically that he will find her before M-3’s six-month contract runs out in March. But also in the same article the journalist explains that Marco proposes taking him out to dinner if he does not find the missing four-year-old before April 30. Unless all such statements are “misunderstandings”, Marco is in danger of leaving everyone with hopes that are not fulfilled.

When I start to touch on these themes – the claim, for instance, that M-3 traces around 300 missing people a year – Marco is quick to clarify. He says that, of the 1,000 or so investigations his agency undertakes every year, “between 100 and 200 involve English people who owe money and have fled England for Spain; the same with Germans, etcetera, etcetera”. This makes it sound as if much of the agency’s work

is little more than aiding bailiffs or debt-collecting, though I do not believe this to be the case. But when I ask him to elaborate on the 23 missing children his mother is reported to have said the agency has located in the past, Marco eases himself away from the table for the first time, tilting far back in his chair. He cannot talk about that on the grounds of confidentiality, he says. Shortly after this, his cousin Jose Luis, who has sat mostly silent until now, calls time on the interview with a chopping motion of his hand.

As I leave M-3’s office I pass another door discreetly announcing it is that of a private Swiss bank. As I take a seat in the restaurant downstairs for lunch, I notice Marco’s father, Francisco Marco Puyuelo, sitting close by. I nod at him and smile. He does not smile back. I have heard unsettling reports about Puyuelo.

He is rather menacing-looking, and I feel uncomfortable as he sits staring at me, slowly spooning chocolate ice cream into his mouth.

) ) ) ) )

It is easy to feel a little paranoid in Barcelona. Nearly every quarter seems to have its own private detective agency. Offices are prominently advertised; on the short ride in from the airport

I pass four. The city’s yellow-pages directory has six sides of listings. According to Catalonia’s College of Private Detectives, the professional association to which private detectives working in the region are obliged to belong, of the estimated 2,900 licensed private eyes in Spain – around 1,500 of them actively working – 370 are in Catalonia, mostly Barcelona.

The city has traditionally had a prestigious record for private investigation. One of Spain’s most well-known detectives, Eugenio Velez-Troya, was based in Barcelona, where he helped set up the first university course in private investigation, covering subjects such as civil and criminal law, forensic analysis and psychology.

One of the largest private detective agencies in Spain, Grupo Winterman, founded by Jose Maria Vilamajo more than 30 years ago, is based in Barcelona, though the company now has 10 offices in different cities with a staff of around 150. Vilamajo is the only detective prepared to talk on the record; the others prefer to remain anonymous for fear of professional reprisal. He talks about how Barcelona came to have so many private detectives, pointing out that competition in the field is now so intense that it is pushing individual agencies to “specialise”.

Vilamajo is the only private detective apart from Marco to receive me in a spacious company boardroom, which, it strikes me, might be the model on which Metodo 3, anticipating rapid expansion, is basing its new office setup.

I meet the other private eyes either in bars or in their more modest premises, with more cloak-and-dagger decor, though nearly all have an impressive array of certificates praising their work. One has the theme music from the film The Godfather as a mobile-phone ring tone.

All talk of the “different way” M-3 has of operating from other agencies in the city. Most of what they say I have no way of substantiating. Traditionally, they say, M-3 has wined and dined clients more than others, sometimes holding grand “round-table” suppers to which it invites important figures in the community.

One ageing sleuth slides across the table a Spanish newspaper article entitled “Detectives with marketing” , in case I might have missed it. A short piece referring to the book Marco recently co-wrote about the alleged charity conspiracy, it makes the point that the book “is another step in the direction of incorporating marketing into the business of private investigation”.

When I ask what’s wrong with a business marketing itself, my question elicits a long sigh. Suddenly I can see that underlying much of the rancour M-3’s rivals feel towards it is a sense that they are not “old-school gumshoes” working in the shadows. One of their criticisms of Marco is that “he doesn’t know much about the street. He’s good at theory. He’s like a manager, always dressed up in a suit and tie”.

So he has a team of others to do the legwork, I argue. Another long sigh. “Not as many as he claims,” comes the response. On this point, all those I speak to agree. None believes M-3’s claims that it has 40 people working on the hunt for Madeleine, since the maximum number M-3 employs in its Barcelona office, they believe, is a dozen, with another few in its Madrid branch.

But again, I point out, it could have any number of operatives working for it in other countries, namely Portugal and Morocco.

My comment draws a weary smile. Metodo 3 company records for the six years up to 2005 appear to show a decline in the number of permanent employees listed – from 26 in 1999 to just 12 in 2005 – although there could be some accounting explanation for this.

Perhaps the most worrying of the detectives’ concerns is the consistent complaint that M-3 is using its involvement in the search for Madeleine to raise its profile and that Marco’s statements about how close he is to finding the child could be seriously prejudicing attempts to find out the truth. “If the agency fails to solve the mystery of Madeleine’s disappearance, that failure will be forgotten in a few years,” said one. “But M-3 will be famous and, ultimately, that is what they want.”

“They are making us look ridiculous,” says another detective. “The English are looking at us and laughing and we are very worried, very upset about it. They [M-3] are denigrating the ethics of our profession.”

To seek guidance on how private detectives are expected to behave, I visit the president of Catalonia’s College of Private Detectives: Jose Maria Fernandez Abril. After making the point that he is unable to speak about any individual member of his professional association, he proceeds to carefully read me a statement that begins: “Following the media impact of affairs in which detectives belonging to the college are involved…” It clearly echoes the concerns that others I have spoken to voice about the conduct of Metodo 3.

“No general conclusions should be drawn about the profession from the actions of any individual,” Abril reads, before helpfully explaining that this means: “You can’t go around saying you are the best in the world, implying that everyone else is somehow worse.”

More importantly, there are repeated references to how members are obliged to comply with the college’s strict code of conduct, which includes: not stating with certainty the result of an investigation and not revealing information about an investigation without agreeing it first with the client.

In other words, if M-3 was to argue that announcing just when it believed it would find Madeleine would help its investigation, the announcement should have been cleared with the McCanns. Given the deep dismay Gerry McCann is reported to have expressed over Marco’s comments about how close the agency was to finding his daughter’s kidnappers and about her being reunited with her family for Christmas, it seems unlikely any agreement over such statements was ever made.

As I leave, Abril informs me that the college has in recent years organised an annual “Night of the Detectives” supper. This year it will be held in March. He invites me to attend. At the supper, various prizes are presented. Among them is one for the fiction author they believe has contributed most to the public understanding of investigative work. This year they have awarded the prize to Dan Brown, author of the worldwide bestseller The Da Vinci Code.

They are a little hurt that he has not replied to, or even acknowledged, their invitation to attend.All this could be almost funny if I were not constantly aware that the reason I have come to Barcelona is because an exhausted little girl enjoying a family holiday went to sleep in pink pyjamas alongside her twin brother and sister on the night of May 3 last year, then disappeared. The anguish and desperation of her parents account for the Spanish detective-agency’s lucrative contract. The boasting and apparent false hopes fed to them by Marco could yet prove to be his downfall.