March 1, 2009

March 1, 2009

Investigation

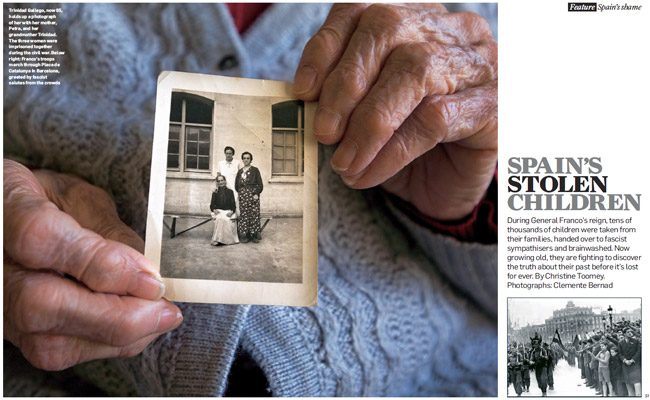

During General Franco’s reign, tens of thousands of children were taken from their families, handed over to fascist sympathisers and brainwashed. Now growing old, they are fighting to discover the truth about their past before it’s lost for ever. By Christine Toomey. Photographs: Clemente Bernad

The only memory that Antonia Radas has of her father has haunted her as a recurring nightmare for nearly 70 years; it is the moment of his death.

Antonia is a small child in her mother Carmen’s arms. Both are looking out through the refectory window of a prison where Carmen’s husband, Antonio, is being held. They see him lined up against a courtyard wall. Shots ring out. Antonia sees a red stain burst through her father’s white shirt. His arms are in the air. Another bullet goes straight through his hand.

After that Antonia believes she and her mother must have fled the prison. But Carmen and her two-year-old daughter were soon arrested. They had been arrested before. That was why Antonio had given himself up, thinking this would guarantee their freedom. But they were the family of a rojo or red — a left-wing supporter of Spain’s democratically elected Second Republic, crushed by General Francisco Franco’s nationalist forces during the country’s barbarous 1936-to-1939 civil war. As such they would be punished. These were the years just after the war had finished, and the generalissimo’s violent reprisals against the vanquished republicans were in full flow.

Antonia is now 71 and living in Malaga. Her memories of much of the rest of her childhood are clear, and many of them happy. “I was raised like a princess. I was given pretty dresses and dolls, a good education, piano lessons,” she says.

It is only when I ask what she remembers about her mother, Carmen, from her childhood that Antonia’s memory once again becomes sketchy. “I remember that she was thin and she wore a white dress. Nothing else. I didn’t want to remember anything about her,” she says with a steely look. “I thought she had abandoned me.”

This is what the couple who raised Antonia told her when she came home from school one day when she was seven years old, crying because another child had said that she couldn’t be the couple’s real daughter since she did not share their surnames. “They told me that my mother had given me away and that my real family were all dead. They said they loved me like a daughter and not to ask any more questions. So I didn’t.”

By then a culture of silence and secrecy had descended on the whole of the country, not just the south where Antonia grew up. These were the early years of Franco’s dictatorship, when loose talk, false allegations, petty grievances and grudges between neighbours and within families often fuelled the blood-letting that continued long after the civil war had finished. In addition to the estimated 500,000 men, women and children who died during the civil war — a curtain-raiser for the global war between fascism and communism that followed — a further 60,000 to 100,000 republicans were estimated to have been killed or died in prison in the post-war period.

Even after Franco’s death in 1975, after nearly 40 years of fascist dictatorship, few questions were asked about the events that had blighted Spain for nearly half a century. To expedite the country’s transition to democracy, the truth was simply swept under the carpet.

Franco’s followers received a promise that nobody would be pursued, or even reminded, of abuses committed. In 1977, an amnesty law was passed ensuring nobody from either side of the bloody conflict would be tried or otherwise held to account. A tacit agreement among Spaniards not to dwell on the past took the form of an unwritten pacto de olvido — or pact of forgetting, which most adhered to until very recently, when the mass graves of Franco’s victims began to be unearthed.

While the majority of his nationalist supporters had long since been afforded decent burials, the bodies of tens of thousands of republicans — many subjected to summary executions — were known to be buried in unmarked pits.

In 2000, a number of relatives’ associations sprang up to try and locate the remains of missing loved ones. When the socialist prime minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero was elected in 2004, the agreement not to rake over the past was ruptured; during his election campaign he made much political capital out of the country’s left-right divide by repeatedly reminding voters that his grandfather had been a captain in the republican army and had been executed by Franco’s military.

To mark the 70th anniversary of Franco’s coup, Zapatero, in 2006, drafted a controversial “historical memory” law intended to make it easier to find and dig up the mass graves of republicans by opening up previously closed archives. In addition, the law — a watered-down version of which was passed after much heated political debate — ordered the removal of Francoist plaques and statues from public places. It also set up a committee to which former exiles, political prisoners and relatives of victims could apply to have prison sentences and death penalties meted out by the Franco regime declared “unjust” — not illegal, given the huge financial implications for the state in terms of compensation this could entail.

Since then, however, such issues surrounding atrocities committed by Franco’s henchmen have become bogged down in a legal quagmire.

Attempts last autumn by one of the country’s leading judges, Baltasar Garzon, to have Spanish courts investigate, as human-rights crimes, the cases of more than 100,000 “forced disappearances” under the Franco regime came up against a judicial brick wall when the country’s high court ruled it had no jurisdiction over such matters, given the 1977 amnesty law. While legal experts continue to argue over whether such crimes recognised by international law are subject to statutes of limitations, regional courts have been asked to gather information about those who disappeared — most of them killed — within their territory.

It is amid this current legal wrangling that one of the least-known chapters of Spain’s sad history has emerged — and it is not about the dead but the living. It concerns those like Antonia, who have come to be known as “the lost children of Franco”.

Both during the war and the early years of Franco’s dictatorship, it is now estimated that between 30,000 and 40,000 children were taken from their mothers — many of whom were jailed as republican sympathisers — and either handed to orphanages or to couples supportive of the fascist regime, with the intention of wiping out any traces of their real identity. Often their names were changed, and they were indoctrinated with such right-wing ideology and religious dogma that, should they ever be found by their families, they would remain permanently alienated from them psychologically.

While similar policies of systematically stealing children from their families and indoctrinating them with lies and propaganda are known to have been carried out by military regimes in Latin American countries, such as Argentina, Guatemala and El Salvador, in these countries trials and truth commissions have long since sought to expose and punish those responsible. But in Spain, the process of uncovering what happened to these children — like that of unearthing mass graves — is only now stirring intense and painful debate.

This is partly because the events happened much longer ago, making them more difficult to unravel. But also because the country’s tense political climate has turned what has become known as “the recovery of historical memory” into such a contentious issue that many argue it should be dropped from the public sphere altogether and remain a purely private or academic matter.

Where this would leave the “lost children of Franco” is unclear. Just how many are still alive and looking for their families is uncertain. But given their advancing years, at the beginning of January Garzon sent an additional petition to regional Spanish courts arguing that, as a matter of urgency, they should offer help to such “children” — now pensioners like Antonia — and families wanting to uncover the truth about the past before all traces of their origins are lost.

Garzon is requesting that DNA samples be taken from those searching for lost relatives — such genetic databases have long existed, for instance, in Argentina — and believes the cases of the “lost children” should also be treated as forced disappearances, ie, human-rights crimes without any statute of limitations. The DNA would be taken from those who are looking for missing relatives and matched with samples taken from those who believe their identity may have been changed when they were a child.

In many ways Antonia considers herself lucky. More than 50 years after she was separated from her mother in prison, the two were finally reunited, briefly — Carmen died 18 months later. Yet despite the apparent happy ending to her story, Antonia displays such deeply ambivalent feelings about her mother as we talk that it is clear that Franco’s aim of psychologically alienating the children of “reds” from their families was achieved. Even now Antonia does not like to be reminded of the name her mother gave her when she was born — Pasionaria, in honour of the civil war communist leader Dolores Ibarruri, known as La Pasionaria. She tuts loudly when her youngest daughter, Esther, writes it in my notebook.

“I believe if she [Carmen] had really wanted to find me when I was still a child, she would have,” Antonia says bitterly, ignoring the fact that when her mother was released from prison in the mid-1940s, like other former republican prisoners, she lived a life of penury, her freedom to work, move and ask questions severely limited.

Mother and daughter were reunited in the end through the efforts of one of Carmen’s older daughters, Maria, who, together with another daughter, Dolores, and son Jose, both then in their teens, had been left to fend for themselves when Carmen was imprisoned with their baby sister. Determined that her mother should see her lost child before she die, in 1993 Maria appealed for information about her sister on a television programme dedicated to locating missing relatives, which Antonia saw, by chance.

It was only then that Antonia learnt that her mother had signed a document handing her daughter into the care of a fellow prison inmate about to be released — prison rules dictated that no child over the age of three be allowed to remain with their mothers — on condition that the girl be returned to her when Carmen herself was freed from jail. Instead, her infant daughter was given, or sold, to the couple who raised her — devout churchgoers who took her to live in Venezuela for some years when she was a teenager, which was when they finally changed her surname to match their own. Carmen had already changed her daughter’s name to Antonia when she was a young child to try and protect her from the wrath of anti-communists.

All this Carmen was able to tell her daughter in the short time they had together before she died. The couple who raised Antonia were already dead by the time of the reunion, but she seems to bear them no grudges, realising they gave her a more comfortable childhood than her siblings had. The deep rancour this still causes between Antonia and her eldest sister, Dolores, is evident, as I see the shadowy figure of Dolores stand briefly outside the window of the downstairs room where I sit talking to Antonia in a rambling house in Sarria de Ter, Catalonia, where she is visiting her daughter, grandchildren and other members of her natural family. Dolores looks in at us, glowers, then walks off, shaking her head. She does not like her sister talking to strangers about the past, and jealously guards her own family secrets. She will not tell Antonia, for instance, where their father’s body is buried — though Antonia knows she carries the details on a piece of paper in her purse — believing that only she, who suffered a life of poverty and misery during and after the civil war, has the right to place flowers on his grave.

Such complicated emotions between siblings and other relatives concerning the events of the civil war and its aftermath are mirrored in families throughout Spain. It is one reason why this period of history was so little discussed for so long. “It is astonishing how many families are from mixed political backgrounds, with maybe a husband on the left and a wife on the right, which meant such things were not discussed over Sunday lunch,” says the historian Antony Beevor, author of the definitive history of the civil war — The Battle for Spain. Beevor believes that public debate about such events is long overdue. “The pact of forgetting was a good thing at the time, but it lasted too long. When you have deep national wounds and you bandage them up, it is fine in the short term, but you have to take those bandages off fairly soon and examine things, preferably in a historical context rather than in a completely politicised one.”

Like many others, Beevor believes Garzon’s attempts to bring such matters before the courts have turned them into a political football that is now being kicked about both by the right and the left for their own ends at a time when Spain can ill afford such bitter polarisation. The country is still grappling with the aftermath of the 2004 Madrid train bombings, carried out by Islamic fundamentalists, continuing terrorist attacks by Eta, growing demands for more regional autonomy, and the fallout of the global financial crisis.

“Why try to drag all this through the courts now. Who are they going to put on trial after all this time? Ninety-year-olds who are beyond penal age?” says Gustavo de Arestegui, spokesman for the country’s conservative Popular party. “Those at the top of the hierarchy of the Franco regime are all dead. Let history be their judge.”

But such arguments miss the point, says Montserrat Armengou, a documentary-maker with Barcelona’s TV channel, who both wrote a book and made a film about Franco’s “lost children” with her colleague Ricard Belis and the historian Ricard Vinyes. “There never has been and never will be a good time to uncover the truth about this country’s past. But the longer we wait the more difficult it will become, because those who were directly affected and know what happened will have died.”

Another part of Garzon’s petition to the courts at the beginning of this year regarding Franco’s “lost children” was a plea that regional magistrates urgently order statements be taken from surviving witnesses to how children were separated from their mothers in Franco’s jails before their testimonies are lost. One such witness is Trinidad Gallego, who we meet in her small apartment in the centre of Barcelona. Aged 95, she talks lucidly, and in a booming voice, about the things she saw when imprisoned with her mother and grandmother in a series of women’s jails in Madrid after the end of the civil war.

As a nurse and midwife, Trinidad was present at the birth of many babies in prison, though few records — either of children brought into the prison or born there — were ever kept.

“I saw some terrible things in those prisons,” she says. “Mothers were kept separated from their children most of the time and all mothers knew their children would be taken away before they were three years old. The priority was to brainwash the children so they would grow up to denounce their parents.”

From the early 1940s onwards, many children of prisoners were transferred into orphanages known as “social aid” homes, said to have been modelled on children’s homes established in Nazi Germany. Their parents were not told what happened to them after that; a law was passed making it legal to change the names of the children, who, thereafter, had no legal rights. The historian Ricard Vinyes has described the orphanages as “concentration camps for kids”. Those who spent time in such places have spoken about how they were made to eat their own vomit and parade around with urine-soaked sheets wrapped around their head.

Victoriano Cerezuelo was registered simply as “child number 910 — parents unknown” when he was placed as a baby in the maternity ward of an orphanage in Zamorra at 8am on April 15, 1944 — the day recorded as his birthday, although he was already weeks or maybe months old by then. When he was five, Victoriano was adopted by a farming couple, but was returned to the orphanage seven years later when the wife, sick of being beaten by her husband, threw herself down a well. “After that I placed an advert in a local paper trying to locate my real parents. As a result, I was beaten to within an inch of my life by a priest, while a nun at the home told me “the more you stir shit, the worse it smells”, recalls Victoriano, 64, as he sits in his Madrid apartment fingering a small black-and-white photograph of himself as a boy. “I would just like to know who my parents were before I die.”

Uxenu Ablana, who spent most of his childhood being transferred from one orphanage to another in Asturias, northern Spain, knows who his parents were. His mother was tortured to death by nationalist forces to extract information about his father, who had been jailed for lending a car to republican officials during the civil war. Uxenu can still recite by heart all the fascist

Falange anthems that were drummed into him in these homes, together with so much force-fed Catholic dogma that, initially, he quibbles about meeting me when I tell him my first name is Christine, so much does he still hate religious reminders. “I have no words to describe all the pain I went through. We were domesticated like dogs, beaten and humiliated, made to wear the Falange uniform and give fascist salutes,” says Uxenu, 79, when we eventually meet in Santiago de Compostela, where he now lives.

“I am not a lost child of Franco — I am dead. They killed me, what I could have been, when I was put in those homes. They brainwashed me against my father and true Spanish society.”

When he was able to leave the orphanage at the age of 18, Uxenu, whose name had not been changed, was tracked down his father, who by then had been released from jail. But the two were strangers and quickly lost contact. “I had to keep quiet for so long about what happened to me, and I still feel like a prisoner in a society that does not want to talk about the past,” says Uxenu, whose wife is so opposed to him recalling his childhood experiences we have to meet in a restaurant.

The problems that Uxenu, Victoriano, Antonia, and who knows how many more, have faced and continue to face regarding their past as Franco’s “lost children” is justification enough in the eyes of Armengou and others for Garzon to pursue his attempt to get what happened to them classified as a crime against humanity. Fernando Magan, a lawyer for a group of associations representing Franco’s victims, vows he will take the case to the European Court of Human Rights and the United Nations if Spanish courts fail to properly address the issue. “Justice is not only about prosecuting those responsible for crimes, it is about helping victims uncover the truth about what was done to them or to their loved ones — in this case in the Franco era,” argues Magan.

To those who say it is time Spain turned the page on this period of its past, Uxenu voices what many feel: “Before you can turn a page you have to understand what was written on it. Unfortunately here in Spain, we are still at war — a war of words and feelings.”