November 29, 2009

November 29, 2009

Investigation

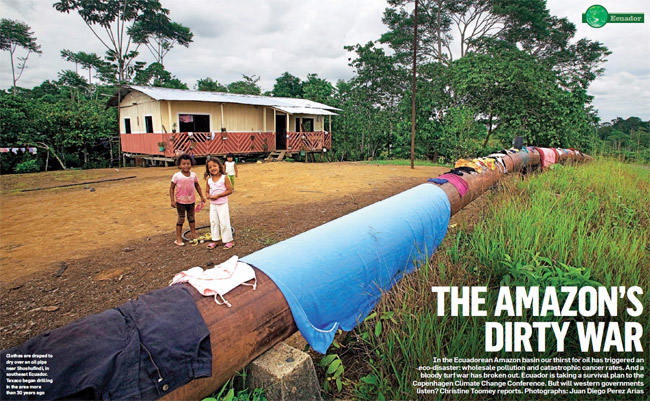

In the Ecuadorean Amazon basin our thirst for oil has triggered an eco-disaster: wholesale pollution and catastrophic cancer rates. And a bloody turf war has broken out. Ecuador is taking a survival plan to the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference. But will western governments listen?

Torrential rain has washed away the blood where the family fell under a hail of wooden spears. But memories of what happened this summer are still fresh in the minds of those who live and work here.

At first the security guard inside the perimeter fence of the oil drilling station is nervous and warns us to keep our distance as we approach. Darkness is falling and he is alone on duty. But he slowly opens up and describes how, on a morning in August, a 12-year-old girl, run through with two spears nearly 12ft in length, managed to stagger to the front gate of the drilling station to raise the alarm before she collapsed and died.

A short distance away, on a dirt track hidden from view by dense foliage, the bodies of her mother and 17-year-old brother were found by oil workers, pierced by more than a dozen similar spears. Her baby brother had been kidnapped. Before she died, the girl gave a description of their attackers: they were almost entirely naked.

From the shape of the spears and the coloured feathers on them, they have since been identified as almost certainly belonging to one of the world’s last known “uncontacted” tribes: the Taromenane.

Sandra Zavala, her son Byron and daughter Damaris were easy targets, stragglers behind a group of men with machetes who were working to clear a path through the rainforest. Oil exploration in the forest has encouraged illegal logging and colonisation by poor Ecuadoreans from other parts of the country and led to clashes in which many innocent lives have been lost. Sandra, 35, and her children were just the latest victims in a vicious turf war triggered by our thirst for oil.

Close to Ecuador’s borders with Colombia and Peru, this swathe of territory — much of it now included in the Yasuni national park — is also at the forefront of another, global battle. Yasuni is home to a vast array of rare flora and fauna. It has the largest number of tree species per hectare in the world (more in just one hectare than the whole of North America), together with endangered monkeys, pumas and jaguars and 44% of the entire bird population of the Amazon basin stretching far beyond its borders. But beneath the surface is immense wealth of a different kind: more than a billion barrels of crude oil.

Ecuador’s president, Rafael Correa, is promoting a plan he describes as “not only simple, but audacious and revolutionary”. In the run-up to next month’s UN climate-change conference in Copenhagen, he and his team have been circling the globe to drum up support for a scheme that would leave 850m barrels of oil in the eastern section of the park untouched underground.

In return for not pumping this oil, they are asking other countries to pay Ecuador $350m a year for the next 10 years to compensate for lost income. Correa’s plan is designed to preserve what is left of Yasuni’s unique biosphere and the territory of its indigenous people and would also prevent carbon-dioxide emissions caused by extracting and burning this oil — an estimated total of 410m metric tons of CO2.

In Yasuni, meanwhile, the battle is raging for control of resources. Active drilling and oil production are taking place in several blocks of land, including one close to the heart of the park operated by the Spanish conglomerate Repsol and two in the northwest operated by the Chinese company Petro Oriental, which runs the drilling station where the Zavalas were killed. The family came from a small community of settlers, Los Reyes, that has sprung up close to the oil wells.

The Taromenane have killed settlers and illegal loggers before, in retaliation for attacks on their dwindling numbers. In 2003, 26 Taromenane women and children were ambushed and killed. Their attackers were never caught but are thought to have been Waorani, another, larger group of indigenous people, many of whom have been co-opted to work for the oil companies.

In an effort to protect the territory of these indigenous communities, the southern half of Yasuni and an area beyond was marked out two years ago as a so-called “untouchable zone” where they could continue their hunter-gatherer existence undisturbed. But the Taromenane have no way of knowing that such a zone exists, let alone its limits. They only know that their ancestral land is under threat. Those who attacked the Zavala family a few miles beyond the boundary of the zone did not keep the kidnapped baby. They stole back to the area two days later and left the infant propped in a hollow tree trunk close to where his mother had died. He was quickly found, dehydrated but otherwise well.

In line with official policy of not forcing contact with the Taromenane, no action was taken in the aftermath of the killing. (In the past, indigenous peoples have been decimated by diseases brought in through forced contact with the outside world.) “We don’t want to put these tribes in a crystal box and conserve them for eternity,” says a government spokesman, Eduardo Pichilingue. “We want to leave it up to them to decide how and when they change. They have that right.”

Instead of punishing the tribe, the government called for the Hormiguero Sur drilling station to be closed down. But as we stand talking to the guard there two months later, straining to make ourselves heard above the roar of a generator pumping oil, it is clear this order is being ignored. Attempts to challenge Petro Oriental executives at a nearby headquarters are met with indifference.

“We can’t comment,” said Luis Gomez, director of community relations. “All I can say is we get blamed for everything bad that goes on around here. It’s even our fault, they say, when a wife leaves her husband.” He laughs, before hastily ushering us out of the floodlit compound.

This brushoff is mild compared to the repeated stonewalling of the Spanish company Repsol, which has drilling operations close to the heart of Yasuni. In addition to triggering tensions of the kind that led to the deaths of the Zavala family, Repsol has recently been accused of causing some of the worst environmental destruction in this part of the Amazon rainforest, with a series of huge oil spills. According to the Spanish branch of Greenpeace, Repsol sent 14,000 barrels of crude oil gushing over the landscape in February. The spill caused such widespread pollution that environmental activists called for all concessions granted to Repsol throughout the Amazon region to be withdrawn. Repsol refuses to comment.

But when we arrive by motor launch at Repsol’s first security outpost, we find a notice pinned on a perimeter fence warning employees: “It is your responsibility to maintain strict secrecy regarding your work.” As our photographer starts taking pictures, he is warned by security guards with submachineguns to put his cameras away.

At the scientific station: impasse. Repsol backtracks on its offer of co-operation and says it has nobody for us to liaise with locally. Fearing repercussions from the oil company, which controls all access roads to and from the university-run scientific station, academic staff there become anxious and reluctant to talk. They withdraw an offer of a truck to visit indigenous communities several hours’ drive away and seem keen for us to leave.

Stark evidence of the long-term destruction caused by oil companies in Ecuador’s Amazonian rainforest lies less than 100 miles northwest of Yasuni. In parts of the rainforest as yet untouched by the incessant search for oil, the song of rare birds and the screeching of monkeys fill the air. But close to the oil installations, the only signs of wildlife are the vultures circling on thermal currents above flare stacks burning off unwanted gas and emitting an acrid smell.

People in the sprawling area between the oil towns of Coca and Lago Agrio, which has been booming since the 1960s, have had a chilling foretaste of what others may face unless the drilling is contained. Here, in a region dubbed “the Rainforest Chernobyl”, decades of drilling by the American giant Texaco, taken over in 2001 by the Chevron Corporation, has led to toxic contamination over thousands of miles. Local communities are suffering catastrophic rates of cancer and other diseases, which has prompted a historic $27-billion court battle. If the 30,000 Ecuadorean plaintiffs are successful, legal history could be made, with the largest damages award ever handed down in an environmental case.

A few miles east of Coca lies the village of San Carlos. Most who live here came to the area in the 1970s to farm along routes cut through the rainforest as oil exploration began. There is little forest left now and little productive farming. Much of the land in this region that stretches north to the border with Colombia was long ago contaminated by millions of gallons of toxic waste, gas and crude oil released untreated into the environment. Most of the inhabitants have depended for decades on contaminated drinking water from polluted rivers and streams. Rates of cancer of all kinds are nearly four times higher than in areas where there is no oil drilling. The incidence of other illnesses such as skin and bone disease, respiratory and digestive problems and spontaneous abortions are also far higher. Most of the people living here have been dependent for decades on contaminated drinking water taken directly from polluted rivers and streams.

Beatrice Mainaguez cradles a photograph of her younger sister Maria, who died of uterine cancer three years ago aged 35. She talks of the “bitter pain” of watching her grow thinner and thinner before she died. Maria, a mother of five, had lived in San Carlos since she was an infant. Her family took their drinking water from a creek that ran close to one of the many oil wells Texaco sank in and around San Carlos in the 1970s and ’80s. It was not until four years ago that the family shack was connected to mains water, and eight months ago to electricity.

A short distance away, Orlando Molina hugs his daughters Sofia, 15, and Yuri, 17, who squirm with embarrassment as he asks them to roll up their trouser legs to show me the bone deformities both were born with.

Orlando says doctors told him the deformities were likely to have been caused by their mothers’ milk being leached of nutrients because she drank water that had drained through soil contaminated by spills from the Texaco wells. His extended family used to live on a coffee farm within a few hundred feet of a Texaco facility on the outskirts of San Carlos that was subsequently taken over by the state company Petroecuador. Both his parents died of stomach cancer, his sister of breast cancer and a brother of prostate cancer.

Orlando spent most of the $4,500 Petroecuador eventually gave him for gobbling up his small landholding on medical treatment to help straighten his daughter’s legs. With the $1,200 left over he bought a two-room wooden shack where his family of six now live.

“Sixty-five per cent of the population around here are suffering from respiratory and gastric problems, skin disease and other illnesses,” says Rosa Moreno, a nurse who has been in the San Carlos area for 25 years. “We don’t have any specialist doctors to diagnose them properly or analyse the causes. But to anyone who lives round here it’s obvious that the problems are related to pollution caused by the oil companies.”

Last year a team of engineers, doctors and biologists submitted a court-ordered report, which concluded that Texaco had polluted streams and drinking water across an area of nearly 2,000 square miles, and caused 2,091 cases of cancer, leading to 1,401 deaths between 1985 and 1998. Chevron’s lawyers say the area’s health problems are caused only by poverty and poor sanitation.

Faced with the possibility of losing the legal battle and having to pay staggering levels of compensation, the company has now made moves to argue before an international court of arbitration in the Hague that the case against the oil companies in Ecuador has been unfair. The outcome is still uncertain: the judge in Ecuador is not due to hand down his judgment until next year.

So far only Germany has made a concrete effort to support Correa’s plan, offering to donate $50m a year for the next decade — on condition that an international trust fund be set up into which donor countries would pay money. All donors would receive “Yasuni bonds” guaranteeing that their contributions would be returned, with interest, if Ecuador were ever to tap the protected oil reserves. Spain, France and Italy have also expressed interest by cancelling debts owed by Ecuador. The British government has not yet been formally approached, but when Correa’s advisers were due to meet MPs earlier this year to discuss the plan, they were told that our parliamentarians were too busy dealing with the expenses scandal.

Correa has made it clear that if he does not get backing for his plan, he will be forced to allow further drilling in Yasuni. “Climate change has been produced principally by the rich countries,” he has said, “and they have a duty to take responsibility for that. What we are proposing is a constructive way to redress the imbalance and stop further polluting of the planet.”

The entire Amazon region is the largest green lung in the world. Its trees and plants produce one-fifth of the Earth’s oxygen and absorb as much CO2 every year as is created by the burning of fossil fuels in the entire EU. Preserving the natural environment in this area is a key element of the fight against global warming.

The bloodbath among the locals must also come to an end: the Zavala family were innocents swept up in the thirst for oil.

But is anyone really listening?