June 3, 2007

June 3, 2007

Investigation

His photographs of naked women in the Soviet Union were banned by the KGB, and he was persecuted for his ideals. But, as his secret body of work shows, this audacious artist could not be silenced

Boris Mikhailov, the artist the KGB tried to silence, slouches in a low armchair in his sparsely furnished apartment in west Berlin. As his second wife, Vita, huddles close to him, wearing shocking-pink tights and black clogs, helping him find the right words in English with an electronic translating device held together with an elastic band, he smiles at her with obvious affection.

Dressed in a dark sweater and trousers, Mikhailov, 69, whose hangdog expression and walrus moustache have led some to compare him to Kurt Vonnegut, is hailed as one of the most important artists to have emerged from the former USSR. Western collectors pay well in excess of £100,000 for his work, and in 2001 he won the prestigious Citibank prize. But for years he was only able to take pictures as a dangerous hobby, under the watchful eye of the Russian secret police. Twice they nearly imprisoned him for taking forbidden photographs.

More than a decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the restrictions that regime placed on everyday life seem almost inconceivable. Any images perceived as portraying life in the USSR as anything but ideal were forbidden. This included images of people smoking, drinking, poor, ill or nude. One photographer who took pictures of people holding cigarettes “in western poses”, for instance, was jailed for three years.

The prohibition of nudity had more to do with social control than moral censorship, Mikhailov believes. “For a totalitarian regime that did not have religion as a means of controlling people, fear and guilt were used instead,” he says. “Guilt was linked with nakedness. Since everyone was naked, everyone was guilty. We were made to feel ashamed of our bodies.” But he was interested in recording reality, not reflecting an officially sanitised view of the world. So some of the earliest photographs he took were of his wife and female friends in the nude. “I was interested in showing beauty, not pornography,” he says. Such arguments carried no weight with the KGB. He was arrested, interrogated and eventually sacked from his job as an engineer in a factory making electrical components for spacecraft. Most factories then had a darkroom where propaganda photographs of production facilities could be developed. Such labs were regularly inspected by the KGB, but Mikhailov, who acted as the factory’s official photographer, had developed and printed his own pictures there as well.

Next he found work as an engineer and official photographer in a water-treatment plant. But again he used the darkroom there for his own work, and again the KGB seized his pictures. This time, they tried to persuade him to become an informer. “To refuse was dangerous. It was considered unpatriotic. When I stayed silent, they lost interest in me and eventually left me alone,” he says. The censorship and the loss of his job incensed him, fuelling his passion for photography further. In the years that followed he continued to take pictures, and themes began to emerge. Underlying everything was a questioning of reality. Born in 1938, he had come of age in the Khrushchev era, when many of the myths propagated by Stalin about the might of the Soviet Union exploded on a shocked nation and the brutality of his regime was slowly exposed. “We began to see the Soviet Union was not so clean. We started looking for other sources of information, comparing the official version with what we saw. This was very important for the way my work developed.”

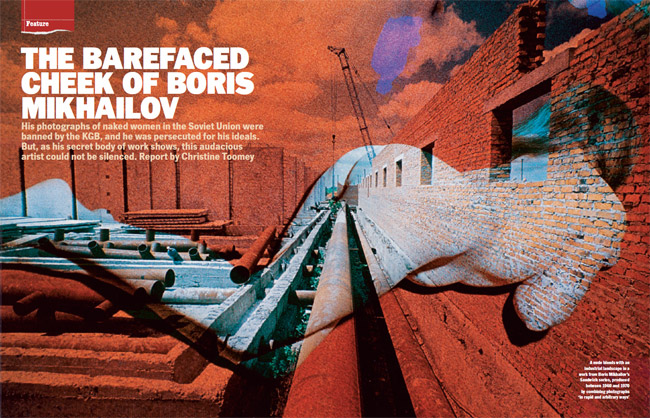

He concentrated on everyday life, people he saw around him, what others might consider mundane. “I wanted to make masterpieces out of photographs that could belong in any family album,” he says. In the beginning this entailed hand-colouring photographs that, through the black market, people paid him to enlarge from negatives. Another early technique was superimposing images to provoke viewers to question their coded meanings. These early “Sandwich” pictures, made between 1960 and 1970, have now been published under the title of Yesterday’s Sandwich. “There was a time when surrealism was seen as kitsch,” he says, to explain why it is only now they are attaining recognition. “I made these compositions at a time when people were more used to interpreting coded messages and signs, when people were on the lookout for any new information and studied images closely in search of their truth and meaning.” So a couple in overcoats staring out over a waterfront have a bare plate and a spoon superimposed on them, to convey the emptiness and boredom of their lives. In another image, an old man’s piercing eyes are formed by the buttons on a military overcoat. The old man, Mikhailov explains, is his father, a former military officer and engineer in Kharkov’s tank factory. In another, a hand wields a giant salami on top of a crane under a dark cloud. This, he says, conveyed the impotence of the state in meeting the basic food needs of its people. “The Soviet Union always boasted about its ability to construct and produce, yet having salami to eat was rare.”

The dual nature of the images reflects the two aspects of his own identity: Jewish and Ukrainian. They also draw on the language of cinema and the idea of a “dissolve” between two shots, he explains. At the factory, he was commissioned to make a short film about its history – which made him certain that it was photography he wanted to pursue. “A film might take a year to make and be seen in a few minutes, while a photograph takes just a second and can have as much impact,” he says with a laugh.

Walking into his apartment, you come face to face with two giant photographs that, for most of us, would be intimidating company to keep. Both are lifesize portraits of homeless people he describes as “living out their last moments”, part of a series of more than 400 searing portraits he shot in the late 1990s called Case History. The series, showing people barely existing on the margins of society after the collapse of the Soviet Union, brought him acclaim but also charges of exploitation. In one, behind a half-naked man with a tattoo of Lenin on his chest, a middle-aged woman with callused hands stands in a ragged overcoat. Thick snow covers the ground, and they look resigned to their fate, beaten down by a life on the streets. In another, a man and woman stand naked, facing each other. The woman’s belly, disfigured by an apparent growth in her intestines, is in the middle of the frame. All four were invited by Mikhailov for a hot meal and a bath at his home in the Ukrainian city of Kharkov – where he was born and still lives half the year – before he paid them to pose for him. “I believe they might be dead now,” he says. “All the homeless I photographed were like the walking dead. I was recording a modern holocaust.”

For someone whose work is so shockingly brutal, he smiles often, frequently gesticulating furiously and, on occasion, leaping up to illustrate a posture or pose. But he also tends to leave the end of his sentences trailing, as if there are things he would rather not talk about, such as his troubled early life. To delve into such a frightening and forgotten underworld is not the work of the timid. Yet what drove him to take up photography seems to have been fear. He was a frightened child who desperately needed a means of self-expression. At first he downplays his early trauma as “just a small thing”. But then he describes being gripped with such dread at the prospect of death as a young boy that he would tear through the streets of Kharkov, trembling and drenched with sweat. Only the exhaustion of running would calm his nerves. Growing up under Stalin’s reign, with a father absent at war, in the Red Army fighting the Germans, might have nurtured anxiety in any seven-year-old. But he believes this terror came from a more general feeling “that the world might end at any moment”. This precocious sense of hopelessness left him with a feeling that he “did not fit in”, was somehow “different” and could not communicate easily with other people.

Given the violent anti-semitism rife in the USSR as he was growing up, the fact that his mother was Jewish but his father was Ukrainian gave him an identity crisis. Then, in his mid-twenties, the best friend with whom he had “shared everything in life” committed suicide. “He was such a strong person, but he could not cope with the sense of smallness of his existence. He imagined something more heroic than the reality of our everyday lives. This was the moment I knew something had to change, that I had to find a way to reach out to other people. For me the way of reaching out was through photography,” he explains. One of his first sexual experiences was with a homeless woman. “I did not see her as homeless, I just saw her as a woman,” he says, the point his Case History series sought to drive home.

Criticism of the series centred on the raw nakedness of some of the subjects he photographed on the streets of Kharkov. Prostitutes pull down their pants, women defecate on the floor, children sniff glue, men expose their cankered penises and other scars – a metaphor, he explains, for the sickness of the country after the collapse of the Soviet Union. “By asking them to remove their clothes I tried to show them as people, tried to look beyond their filthy exterior.” The fact that the people were sometimes paid the equivalent of a month’s wages to pose for him outraged many, who accused him of exploiting misery for artistic purposes. But he dismisses the charges, saying it made no difference to their lives whether he photographed them or not. It didn’t harm them, and the money at least helped them a little.

Spread across the wooden floor of his airy Berlin apartment are dozens of photographs of Kharkov’s youth culture, from which he is trying to make a selection for a possible exhibition at this year’s Venice Biennale. “It is even more difficult taking photographs of people now than it was in Soviet times,” he claims. Despite the restrictions then, he says, people were less self-conscious, and less litigious. Taking street photographs has become so problematic in Germany that he has a certificate from the police giving him permission to take pictures wherever he wants, on the grounds that they are art.

There can’t be many people who would want to display lifesize images of the naked and diseased homeless of Kharkov on their walls in the way Mikhailov has done in his flat. But when I talk to him about this, his view is clear: “Before, we would hang historical paintings on our walls. Now I think it is up to photographers to take historical photographs and to give public space to what is happening around us. It is important to make art of this, to make people reflect.” s