November 14, 2004

November 14, 2004

Interviews

For over 10 years, the children of Nazi war criminals have been talking to the families of Holocaust victims. Has this radical therapy done anything to ease the pain?

His earliest memory is of playing on a swing in his garden as a small boy. Then his father shouts out that he must get off and give his younger sister Ilse a turn. He kicks himself to the ground. But his sister is standing too close behind. The swing flies back into her face. She starts to scream, blood running down her chin.

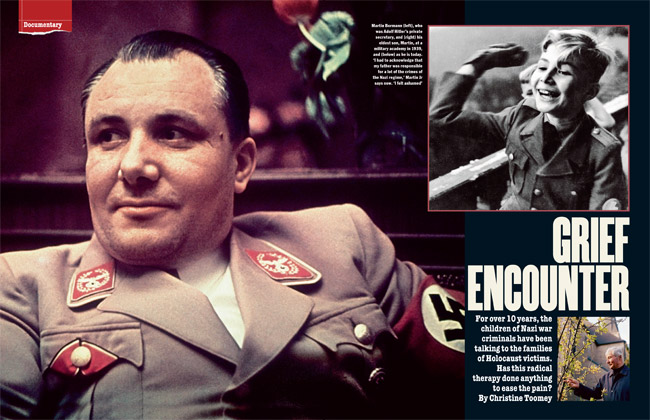

Martin makes a run for it, afraid his father will give him a beating. He hides for hours in a coal bunker close to his home in Pullach, near Munich. It is 1934 and Martin is four years old. When he eventually returns home, the small boy is astounded that his father does nothing. “He just told me that the fear I had felt deep in my bones all that time was my punishment.” Seventy years later, this story is retold with an unsettling air of tenderness. Yet its last line provides a chilling clue to his father’s twisted psyche. For Martin’s father was Martin Bormann, Adolf Hitler’s brutal private secretary and the man who, by the end of the second world war, was second only to the Führer in terms of real political power in the Third Reich.

So close were Bormann and his wife, Gerda, to Hitler that when Martin was born, he was given the middle name Adolf, and Hitler became his godfather. “Godfather” in the Nazi sense of the word, Martin points out, since Hitler and his own father increasingly despised any form of religion. For this reason, Martin, the first of the Bormanns’ 10 children, was the only one to be christened. Because of Hitler’s refusal to oblige by holding him over the baptismal font, that honour was passed to the wife of the Nazi-party deputy, Rudolf Hess. As he sits bolt upright, 74 now and grey-haired, Martin explains all this as if he is speaking about the eccentricities of a squabbling uncle and aunt.

But as he recounts his memories, they become ever more troubling. There are the times he recalls sitting down, with the sons and daughters of others in Hitler’s inner circle, for cake and hot cocoa with Hitler to celebrate his birthday and New Year. “These were never very comfortable occasions,” Martin recalls. “Hitler did not know how to behave around children. He rarely stayed longer than 10 or 15 minutes.”

After the families of Hitler’s cronies moved in the mid-1930s to the Bavarian retreat built for the Nazi elite at Berchtesgaden, and the machinery of war ground into gear, Martin says he saw little of his father. He remembers Hitler giving him a set of toy soldiers for his ninth birthday. But when he bungled his greeting to Hitler — snapping to attention and barking “Heil Hitler, mein Führer!” instead of “Heil, mein Führer!” — his father gave him a sharp slap. And when Bormann received reports that his eldest son was skipping lessons at school, he banished the 10-year-old to a strict military academy at Feldafing in Bavaria. Martin has few memories of his father after that. The last conversation he remembers was when Bormann paid a short visit to Feldafing to have a father-to-son talk about the facts of life. As the two strolled out into the school grounds, Martin, then 13, dismissed his father’s attempt at a heart-to-heart, saying he already knew all about that. But having spent three years carrying out regular drills to become a member of the civil guard and being force-fed extracts from Mein Kampf, the teenager did have one burning question: “What exactly is national socialism?” His father’s answer was simple: “National socialism is the will of the Führer. Full stop.”

The memory that follows this is so grotesque that for most of his adult life, Martin suppressed it deep in his subconscious. Even now his voice gets lower and quieter as he speaks. It was during a brief visit home, he says. He was 14 and he, his mother, sister Ilse and a schoolfriend from Feldafing were invited to tea with Hedwig Potthast, the secretary and mistress of Heinrich Himmler, head of the Gestapo and mastermind behind the Nazis’ “final solution”. “After a while, this woman told us she wanted to show us something: Heinrich’s ‘little room’, she called it.” The tea party was led up to the attic. What they saw there Martin describes as “terrible, just terrible”. The entire room was furnished with human body parts. There was a chair made out of a pelvic girdle, its legs constructed from human thighbones and feet. Lampshades made from human skin, the blood vessels visible, and a copy of Mein Kampf bound in human skin. “At the time, we children did not fully understand what we were seeing. But we sensed our mother’s horror. She pulled us straight from the room. When we got home, my mother grabbed a similar lamp in our living room she had been given by Himmler without realising what it was made of, and threw it out.”

As he finishes telling this story, Martin holds my gaze for an unusually long time, as if trying to judge if I fully comprehend the horror of what he is talking about. This is, of course, impossible. Only those who survived the Nazi regime of terror can do that. Even Martin only felt able to speak of this incident openly for the first time more than 40 years after it happened, and only then in the company of a small group of other children of Nazi war criminals.

He spoke of it again several years later in meetings between this German group and a small number of children of Holocaust survivors — a gathering of tortured souls brought together at the suggestion of an Israeli psychologist convinced that both groups shared similar problems.

Unlikely as this seemed, so profoundly did his conviction prove to be true that the two groups quickly joined to form a tight-knit circle called To Reflect and Trust (TRT). Gently and gradually, by listening at length to each other’s stories over the course of 10 years, they helped each other try to understand what they had struggled with as children and as adults. From 1992 until last year, they met regularly — first in Germany, then Israel and the United States. Since then, they have started talking about what they learnt from these meetings to others in areas of current or recent conflict such as South Africa, Northern Ireland and the Middle East. If the children of those on either side of such a catastrophic gulf as was opened by the Nazis can help each other, they believe, then no attempt at reconciliation, or at least mutual understanding, is impossible. Only by tracing the path Bormann and another of the group — the son of a senior Gestapo commander — travelled long before they joined the others, is it possible to begin to understand such optimism. How any son or daughter could cope with the legacy of such an ominous past is hard to imagine. In Bormann’s case he came close to not trying.

In the chaos and confusion of the last days of the war, as Russian forces surrounded Hitler’s bunker in Berlin, and allied forces advanced from the south and west, the pupils at Bormann’s school were evacuated, issued with guns and told to prepare to fight to the last to defend the “thousand-year Reich”. After being trucked back and forth across country close to Germany’s crumbling front line, Bormann, 15, and a few other boys were billeted in a small guesthouse in Jenbach in the Tyrol, where a group of die-hard Nazi-party loyalists were also staying.

Shortly after midnight on May 1, 1945, news came over on the radio that the Führer had fallen, surrounded by those in his closest circle. “It was as if Hitler had died in battle, together with those around him. It wasn’t until days later that we learnt he had shot himself, and Eva Braun had taken poison,” Bormann recalls. “I was just a boy, but I thought, ‘My God. It’s the end!’ I was convinced my father had died then too. Much later this turned out to be true, though he did not die in the bunker. He took cyanide while trying to flee Berlin on a road near the Lehrter train station.”

This brief summary of events omits the fact that a worldwide manhunt lasting more than three decades was launched when his father’s whereabouts at the end of the war was unknown. Many remained convinced that he had escaped and was still alive. For this reason, in October 1946, Bormann was sentenced to death in absentia at the international military tribunal in Nuremberg. It was not until 1972, during construction work near the Lehrter station, that two skeletons were unearthed near the spot where Bormann’s diary had been found in a discarded leather jacket shortly after the war. Via dental records, the shorter of the skeletons was identified as Bormann’s. Minute scratches on the teeth of both — the other skeleton belonged to Hitler’s surgeon — showed both men had bitten into cyanide capsules. Only with the advent of DNA analysis, however, was there definitive confirmation that one of the skeletons’ bone tissue matched blood samples from the Bormann family. Fifty-four years after the war, in the summer of 1999, his remains were finally released for burial — quietly scattered in international waters, for fear the event would become a rallying call for neo-Nazis. No member of the Bormann family was allowed to attend.

Continuing his account of the night he heard Hitler, and he assumed his father too, had died, Martin recalls how he went out into the garden of the small hotel and, in the darkness, heard a series of shots ring out. Eight Nazi-party die-hards killed themselves that night. “I thought then that this was what I must do too.” He pulled out the gun he had been issued and prepared to shoot himself in the head. As he stood there on the point of committing suicide, he felt a hand on his arm. A schoolfriend had come out into the garden with the same intention. “He stopped me. We stopped each other. We just clung to each other and cried.”

From then on, he vowed to make his way home to his mother and siblings. But much of the region was by then in the allies’ hands and his family had fled further south. After hitchhiking as far as Salzburg, he fell sick with food poisoning and was incapable of going any further. With the help of a German soldier, he was issued with false identity papers and told to seek shelter in the country, pretending he was an orphan. Within months this would be true: his mother, who had been held by British and US intelligence officers seeking her husband, died of abdominal cancer. He never saw her again and learnt of her death in a newspaper.

Under the name Martin Bergmann, the boy did find shelter with the family of an Austrian farmer, an elderly man who came to treat him as a son. It was this man, a devout Catholic, rather than his real father, he says, who changed his life. At night he used to lie in bed listening to the family praying downstairs. “They were not the sort of people who talked about their religion. They lived it. They seemed so at peace with themselves, I thought, ‘I want that peace too.'”

After months in the fields helping the farmer tend cows, Martin started reading the newspapers. They were full of reports of the Nuremberg trials getting under way and the horrors of the concentration camps. He claims he had known little of their existence before this. Given what he witnessed in Himmler’s attic, this is hardly credible. But the night he read that his father had been sentenced to death, he confessed his true identity to the farmer sheltering him. Rather than turn the boy over to the police for questioning, the old man encouraged him to start regularly attending church. Within a short time he converted to Catholicism.

Without similar beliefs, it is easy to view this as escapism. Martin sees it differently: “I never thought I could run away from my past. I have to live with it. But my salvation was an enormous gift from God. It allowed me to deal with what had happened. I felt great shame. My God, I still feel it. You cannot blast it away, this collective shame. What happened in Germany from 1933 to 1945 was terrible,” he says slowly, looking into the distance as if no longer engaged in conversation, but lost in thought. “I felt ashamed, in pain, helpless. I had to acknowledge that my father was responsible for a lot of the crimes of the Nazi regime. My father forced the mass deportations, the slave labour. My father’s signature was on so many orders.” Not escaping from his past, perhaps, Martin did escape the continent on which its worst atrocities were committed. He buried himself in another heart of darkness. After being ordained as a Catholic priest, he became a missionary in the Belgian Congo.

During the six years he spent there in the 1960s, the region was plagued by civil war; he was kidnapped three times by rebels, once narrowly escaping execution by a firing squad. After contracting a severe gastric infection, he returned to Germany for treatment. Shortly after his release from hospital, the car he was driving was involved in a head-on collision and he fell into a deep coma. Whether this collision was really an accident or due to a subconscious death wish is open to question. If the latter, it was once again thwarted: he regained consciousness, though his legs were so badly crushed it was thought both would have to be amputated. Nursed back to health by a Dominican nun, he realised he would never be able to return to the rigours of work as a missionary, and asked to be released from holy orders. Shortly afterwards, Cordula — the nun two years his senior who had acted as his nurse — applied for a similar dispensation. On November 8, 1971, the couple married.

For 20 years they lived a quiet life as religious-studies teachers in a pretty, medieval market town near Hagen in northwest Germany. It is here, in the beer cellar of a hotel, that we sit talking. Even today, though the son is in his mid-seventies and the last pictures taken of his father date from 1945, when the Nazi henchman was in his mid-forties, there is a striking resemblance between both men. Both share a strong, square jaw, broad forehead, hooded eyes and wide, thin lips. But while Bormann Sr is invariably pictured in military uniform, his son wears a tweed jacket, denim shirt, casual trousers and thick-soled white orthopaedic shoes. As a result of his car accident, he still walks unsteadily. His German is precise and he speaks in a slow monotone, almost as if he is recalling someone else’s life and not his own.

As he talks, Cordula, who still prefers to be known by the name, meaning “Little Heart”, that she was given when she became a nun, sits beside him, sometimes stroking his arm, laying her head on his shoulder and soothing him with the words “Lieber Martin” — “Dear Martin”. Everything in their lives changed, she says, when he received a telephone call one day from the Israeli professor Dan Bar-On, of Ben Gurion University of the Negev. He wanted to know how children of Nazi perpetrators had been affected by their parents’ past. “When Dan Bar-On came it was the worst time,” says Cordula, pressing her hand on Martin’s to quieten his protest. “I know because I lived this with Martin. Bar-On pulled out all the drawers — the spiritual drawers, you understand — where everything had been stuffed, and all that Martin thought he had already overcome was there again.” Only then, she says, did her husband understand what it really meant. “He read all the books, all the documents of the Nuremberg trials. He watched the videos of the concentration camps, all those terrible things, and he sat there crying, crying, crying. Before, he was such a joyous person. He laughed and made jokes. We sang. But since then, he is a very sad person.”

Some have criticised Martin for hiding behind his faith.

A Canadian writer, Erna Paris, concluded that “Theology has allowed [Bormann] to transform pain and grief over a criminal father into a bland, bloodless paste”. Even his wife concedes that his religion acts as emotional armour: “It is good that Martin has his faith. It keeps him protected.”

But while the offspring of other prominent Nazis such as Hess’s son Wolf Rüdiger and Himmler’s daughter Gudrun — who helps run a support network for ageing Nazis, called Stille Hilfe, or Silent Help — continued to vigorously defend their father’s wartime actions, Martin has done the opposite. Since retiring as a teacher 12 years ago, he has travelled throughout Germany and abroad, giving talks and taking part in meetings in schools, colleges and community halls denouncing the crimes of the Third Reich. Fearing angry reactions — some old Nazi sympathisers called him a Nestbeschmutzer, dirtying his own nest — tight security was sometimes organised for these meetings. But public reaction, especially among younger Germans eager to learn about the past, says Martin, was overwhelmingly positive. And he would never have spoken out so publicly, he believes, had he not been forced by Bar-On to confront the truth.

When Bar-On began speaking to the children of Nazi officers in the late 1980s, there was a feeling that acknowledging they also suffered was morally offensive. There was a feeling among other psychologists that it equated what they had gone through with the suffering of Holocaust survivors and their children at the hands of the Nazis. But the more Bar-On spoke with the children of both “sides”, the more he felt they were “in some ways opposite sides of the same coin” and that, if they met, they could help each other. Both, he says, “suffered tremendously from the silence surrounding their past”.

Dr Joe Albeck, whose parents were among only six survivors of a Nazi labour camp in Poland, likens this silence to “growing up with an elephant in the room”.

As a child, he says, “you learn there is something going on in the world that you can’t put a name to and nobody will acknowledge”. Now a Boston, Massachusetts-based psychiatrist, he admits he had deep reservations about Bar-On’s proposal for such a meeting. But when the group — eight Germans, four Americans and four Israelis — met for the first time in Wuppertal, Germany, in 1992, they all felt able to talk openly about the past in a way they never had before. “All the players from both sides, so to speak, were there. The historical circle was complete.”

Julie Goschalk, also from Massachusetts and a therapist whose parents were survivors of the concentration camp Bergen-Belsen, says she was shocked by the “horrific shame” the Germans felt. “Had they said, ‘Well, yes, we hate our fathers, but it’s nothing to do with us,’ it would have been an awful lot harder to make any connection with them,” she says. “But we saw that their lives had been destroyed by what their fathers did. The burden they were carrying was their parents’ burden.” Goschalk admits she was also terrified at the thought of the meeting. When she shook Martin’s hand, her reaction was: “My God, whose hand have I just had in mine?” But her hatred of Germans was so great, she says, she was in some way “guilty of what the Nazis had done in hating a whole race”. The meetings allowed her to see them as individuals, people who had suffered too as a result of the past. “After the very first meeting, listening to everyone’s individual stories, I felt my hatred melt away,” she says. “That was liberating.”

Relatives on both sides also struggled to accept any good would come of these meetings. With the exception of his sister Ilse, who died several years ago, Martin says his younger siblings want little to do with the past. For the Germans, it was invariably their mothers who had tried the hardest to cover up the reality of who their father was.

Some did not discover the truth about their fathers until they were young adults and their fathers were arrested, put on trial and served prison sentences. Dirk Kühl is grateful that he was spared this. His father was head of the Gestapo in Braunschweig, and was hanged by the British for war crimes in 1948. Kühl, 64, tries hard to keep calm as he speaks of the past in his spacious home in Nuremberg. “I’m glad I did not have to deal with knowing my father,” he says defiantly. “He paid for what he did, and that freed me.” But as he talks, a darker story emerges. When he found out the truth about his father, Kühl had a nervous breakdown.

He was just eight when he saw his father, Günter, for the last time. The meeting was in a tent at a temporary prison run by the British. “He told me to be a good son, and gave me some chocolate and some crayons in a box with a picture of William Tell on it. I can still recall the cover of that box better than I can my father’s face. I did not know I would never see him again.” After that, Kühl says, his father was todgeschwiegen — silenced to death; rarely mentioned. After a few years, his mother said his father had died in prison. Her son appeared to accept this; many schoolfriends had lost fathers too. But Kühl says he always sensed there was something he was not being told. When he was 16, he was sent to stay with a relative in Holland. It was this relative who told him that his father had been executed by the British for war crimes — even though, he was told, his father was “only doing his job”.

Kühl says he accepted this impression that the death sentence was not deserved, and he became obsessed with rehabilitating his father’s reputation. But when he tried to enlist the help of a prominent lawyer, he was told

“forget it”. “The message I received from that lawyer was that he was shocked I could even consider my father could be rehabilitated after all the awful things he had done.”

Furious that his mother had deceived him for so long, Kühl, an only child, refused to talk to her for years and, at 19, had a nervous breakdown. In an incident reminiscent of what happened to Bormann, he was involved in a car crash. He describes being “pieced back together” in a clinic in Bavaria. But it was not until he started studying to become a history teacher and met the woman he would marry — a Jewish refugee from Russia, who had narrowly escaped being sent to a concentration camp as a child by the Gestapo — that he slowly started to discuss his father. With her support, he started reading the transcripts of his father’s trial. “After that, whenever I saw a man walking along the street with a briefcase, I had to admit that when my father carried a briefcase, it was not full of papers about water pipes or electricity: it was full of orders to punish people, kill them, put them in concentration camps. It was murder by administration. I fell into an emotional abyss.”

While Kühl’s first wife, Lena, who has since died, helped him begin to confront his past, he says it was not until he began taking part in the meetings organised by Bar-On that he really learnt to “fully face the truth — without any camouflage”. Kühl says he will never find peace. “There is so much rage that runs in my blood about what was done.” The most frightening realisation of all, he says, when he began to look at the human being behind the man his father became, was acknowledging how quickly events had changed him. “Evil comes step by step,” says Kühl. “None of us knows what we are capable of and I don’t trust anyone who says, ‘I would not have done that’ — I have looked far enough into the abyss not to trust such statements.”

The next day, before formally shaking my hand and walking unsteadily away with Cordula on his arm, Martin Bormann said something similar. Because of failing health, this is one of the last times he is prepared to speak publicly about the past. “I owe my life to my father. I have to thank him for that. But I have had to learn to distinguish between the man I knew as my father and the man I have learnt about who was a complete stranger; a man who was totally ruined by Hitler’s ideology. A man who did everything he did of his own free will, with his eyes wide open.”

As a result of his many meetings with Kühl, Bormann and the others, Bar-On says his view of human nature has changed profoundly: finally he has come to agree with their conclusion. “I no longer have the luxury of believing there are evil people and good people: these two possibilities lie very close together and this means we are all much more defenceless,” he says. “You cannot simply ‘screen out’ the evil people. The important thing is to make sure you do not create the circumstances where this side of human nature can thrive.” His words in my ears, I switch on the evening news and listen to a report of the latest beheading in Iraq.