April 10, 2005

April 10, 2005

Investigation

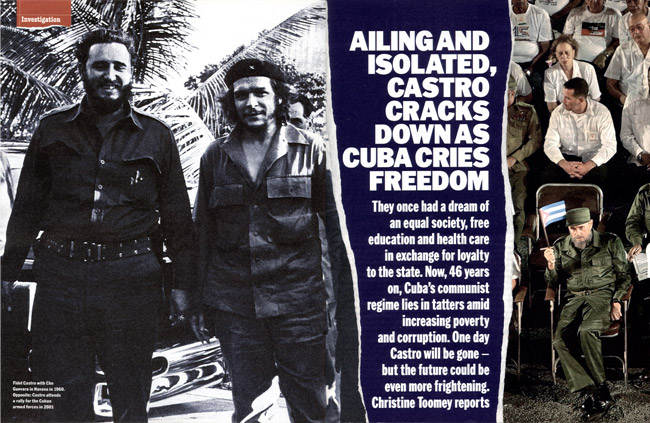

Castro cracks down as Cuba cries freedom

They once had a dream of an equal society, free education and health care in exchange for loyalty to the state. Now, 46 years on, Cuba’s communist regime lies in tatters amid increasing poverty and corruption. One day Castro will be gone — but the future could be even more frightening

Jostled in the back of an antiquated car on a tortuous ride through the Cuban countryside to avoid police checkpoints, Laura Pollan recalls the words of a song. Tapping her fingers on the worn leather seat, she begins to sing in a low voice: “We are the vanguard of the revolution, our books held high, bringing all Cuba literacy! Through valleys and mountains we carry the means to give light to truth!”

Translated roughly from Spanish, the words to this “Hymn to Literacy” lose much of their verve. But as she sings, Pollan, 56, flourishes her hands and smiles. She remains animated as she recalls how, as a 12-year-old girl, she had volunteered to join the ranks of nearly a million Cuban schoolchildren sent out into the countryside in the spring of 1961 to live with illiterate peasant families and teach them how to read and write.

The year before, Fidel Castro had vowed to the United Nations that one of the first aims of the Cuban revolution would be to make sure that every Cuban — an estimated 40% of whom were illiterate — could read and write within a year. It was something never before believed achievable in the developing world.

But less than 12 months later, tens of thousands of teenagers were marching through the streets of Havana carrying giant mock pencils to celebrate the accomplishment of this goal.

It was an achievement that caught the world’s imagination and helped define the romantic image of the revolution that had ousted the country’s military ruler, Fulgencio Batista, a dictator so brutal that he resorted, among other atrocities, to the public castration of opponents.

Pollan remembers her uniform, the lamp she carried for night-time study, thousands of which were donated by China’s communist regime, and the reading glasses the brigadistas were given to distribute to those who needed them — a donation by another communist ally, Bulgaria.

“I have great memories of that time,” says Pollan, who went on to become a teacher. “There was so much enthusiasm. The revolution was still young. It had not yet shown its true face.”

We are travelling to Havana from the central province of Villa Clara, where Pollan had been trying to visit her husband in prison. She had been refused. It was Christmas Eve and she was allowed to leave him a bag of apples and a letter. But prisoners such as her husband are permitted visitors only once every three months, if that.

To the Cuban government, her husband, Hector Maseda, is an enemy of the state. His crimes include founding Cuba’s opposition Liberal party — all opposition parties are banned — and writing articles about the explosion of sex tourism in Cuba and the history of the country’s opposition movement. These were published in magazines and websites in Europe and the US; all Cuban media is state-controlled, freedom of expression being an alien concept.

As the world’s attention was focused on the imminent invasion of Iraq in mid-March 2003, Maseda was among 75 government critics — mostly journalists, poets, independent librarians and political activists — arrested by the Cuban authorities, subjected to summary trials and sentenced to lengthy prison terms. In Maseda’s case, that was 20 years on charges amounting to sedition. It was the most severe crackdown on Cuba’s dissident movement since Castro led his guerrilla forces to victory in 1959.

Pollan stood by helpless that night as her husband was bundled out of their modest home in central Havana. Together with his typewriter and a fax machine, books were also confiscated. Among them were the works of Vaclav Havel, the playwright and former Czech president who led his country’s opposition movement until the fall of its communist regime. As he was led away, Maseda took his wife’s hand and told her: “Laura, do not feel ashamed. I am not a murderer or a thief. I have done nothing but defend my ideas.”

The rot of the Cuban revolution lies in the contrast between these two very different scenes painted by Pollan. The first: her recollection of a time of optimism, altruism and cataclysmic social change. The second: an act rooted in paranoia, stifling control and absolute determination by Castro to hold onto power at any cost.

For 46 years after Fidel Castro, the world’s longest-ruling leader, stood before the United Nations promising to transform his country into a tropical utopia, this island nation of 11m has been driven to exhaustion, and millions of them to despair, by the implacable will of its “maximum leader”. Even now, after the vow by the revolution’s ideologue Ernesto “Che” Guevara that future generations of Cubans would be “more perfect”, schoolchildren start their day with a salute and the solemn vow “Seremos como Che!” — “We will be like Che!” But what, really, has become of this generation of Che’s children and grandchildren? (Had he lived, he would now be 76.) And what is likely to become of them when his former comrade-in-arms, 77-year-old Castro, no longer holds Cuba’s reins of power?

For more than 40 years, all administrations in the US, which once occupied Cuba militarily and then dominated it as a debauched mafia playground, have tried to topple Castro. First through the bungled CIA-backed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, then in a series of bizarre assassination plots, including one to plant toxic powder in Castro’s clothing. Throughout, the US has held the island in the stranglehold of an economic embargo. Despite all this, Castro has seen off nine American presidents and is determined to increase that count.

Yet in George W Bush he appears to see a more formidable foe. One reason for the roundup of political opponents such as Maseda is believed to have been speculation that countries other than Iraq accused by the state department of being “state sponsors of terrorism” could become US military targets. The threat of US invasion was portrayed as so great by the Castro regime that three weeks before Christmas, more than 1m Cuban soldiers, reservists and support teams were mobilised in a military exercise dubbed Bastion 2004. So extensive was the coverage of the simulated invasion on all state TV channels, and so pervasive the sound of military alarm sirens, that some older Cubans thought they were genuinely under attack.

For most Cubans, however, there is only one way that Castro will ever relinquish his hold on power. This is by means of what they refer to obliquely as “biology” — his death. Ever astute about his own image, the maximum leader makes light of his age, and jokes about his immortality regularly make the rounds. Like the one about the baby turtle expected to live to 100 years, which he refused as a pet on the grounds that it would “make me sad when it passed away”.

But a brief glimpse of what is likely to happen if, as seems almost certain, Castro dies while still in power came just six months ago, when he stumbled and fell after delivering a speech in the capital of Villa Clara province, Santa Clara.

Santa Clara is the holy grail of idealistic fervour for many foreign tourists piling into this dusty provincial town. It is here that Che Guevara’s remains were brought from Bolivia, where he was killed in 1967 after attempting to foment revolution in the rest of Latin America and Africa. His vast, white marble mausoleum lies on the edge of town, and it was here that Castro tripped and fell last October. The fall was the latest in a series of health scares. Although he is still capable of delivering interminable speeches, his voice has become increasingly tremulous in recent years and his hands sometimes shake, leading to speculation that he is suffering from the early stages of Parkinson’s disease. Several years ago he collapsed owing to heat exhaustion during a speech. When he finished his speech in a TV studio later that evening, he joked that he’d been “pretending to be dead to see what my burial would look like”.

But while film footage of the aftermath of his most recent fall last October was broadcast around the world, Cubans say the moment their leader began to stumble to the ground, the image on the country’s state-run television station became blurry. It was then quickly replaced by cartoons of Popeye and Bugs Bunny.

What his countrymen did not apparently see was Castro being helped into a chair as doctors danced attendance (he had fractured bones in an arm and a leg), nor the rehearsed response of Communist-party functionaries who were present raising their fists and chanting “Viva Raul!” as Castro’s brother and heir apparent, Raul Castro, was hailed. Had the fall proven fatal, he would have been anointed immediately.

Less than a mile from the mausoleum, Guillermo Farinas eases his wheelchair into the small, enclosed porch of his mother’s home and hands over a photograph of himself taken shortly after his most recent release from jail. In it he is emaciated. The scars where tubes were inserted into his stomach for force-feeding are still raw. Farinas, 42, has staged numerous hunger strikes over the past six years during prison terms meted out for opposing the government. He repeatedly yanked feeding tubes out of his stomach, vowing he’d die for his ideals. He was eventually released from jail and placed under a form of house arrest. But malnutrition has left him so weakened, he is not yet able to walk.

Farinas — like Pollan and all others identified here — realises speaking out could bring further reprisals. But all are determined that the reality behind the image carefully crafted for tourist consumption of Cuba as a sultry Caribbean isle offering sun, salsa, cigars — and, though the state denies it, cheap sex — should be widely known.

“Nobody here discounts the possibility that Castro, or Bush, could provoke hostilities between Cuba and the US,” says Farinas. “And in many ways this would suit Castro: if he dies fighting, he remains a myth. But the real danger is the apocalyptic language this regime has used for so long, planting the idea of violence in people’s minds for after he dies.”

Aside from street placards proclaiming “Socialism or death!”, Castro’s communist regime has fostered deep hatred and resentment, not least that orchestrated by the state against, and felt by, the more than 2m Cubans now living in exile. The idea that there will be a big welcome to a returning flood of exiles when Castro goes is scoffed at by most Cubans. While many older ones who remember the brutal Batista regime revere Castro — though 70% of the population was born after the revolution — most are genuinely afraid of what will come after his demise. With good reason.

Some predict if the baton is passed, as planned, from Castro to his 73-year-old brother, an even more authoritarian regime could be imposed. As head of the armed forces, which now enjoy great privilege as they control the most profitable two-thirds of the country’s struggling economy, the vested interest of Raul and his military cohorts in maintaining the status quo would be intense. Yet little of the legitimacy Fidel Castro has as the revolution’s figurehead is expected to pass to his brother. The hunched, elfin-like Raul, whose drinking is said to have left him with serious liver problems, is widely disliked — particularly among the young, who see him as a grey apparatchik.

But if Raul Castro fails to stamp his authority quickly, or dies before his brother or shortly afterwards, infighting among the Communist-party elite could lead the armed forces to step in and form the sort of military government led by General Jaruzelski in Poland in the 1980s. Says one European who is based in Havana: “The perception in Europe that there will be the equivalent of the fall of the Berlin Wall here is not how the situation is viewed by Cubans. For some, Cuba’s civil war is ongoing and they don’t rule out a second round of hostilities.”

Anachronistic as it seems, no visitor to Cuba can fail to sense that this is an island stuck in a past era. The many lumbering 1950s American Chevrolets and puttering Soviet Ladas still on the roads are one trivial sign. More potent is the sight of dozens of workers standing to attention along Havana’s vast curved corniche, the Malecon, swearing allegiance to the revolution and holding aloft documents marking them out as especially fervent party loyalists.

But the fundamental difference between Cuba and former eastern-bloc countries such as Poland, which threw off communism’s shackles 15 years ago, is not only that Cuba’s revolution was home-grown, but that it has virtually no civil society. Internal opposition, in contrast to the often-bellicose exile community, is both painfully weak and disorganised. To follow Farinas’s story and those of other government opponents is to understand not only why, but also how, this makes an eastern-European-style “velvet revolution” post-Castro highly unlikely.

Like many of those interviewed, Farinas was initially the epitome of Che Guevara’s “new man”. Raised in a revolutionary household — his father fought Batista’s forces and then served in the Belgian Congo with Guevara — he spent his youth training as a military cadet before going to Africa in 1981 to help defend Angola’s Marxist regime. There he won two distinguished-service medals and was sent on to the Soviet Union for further military training. After returning to Cuba he was discharged on medical grounds. “I believed in the revolution until my ideals were crushed blow by blow,” says Farinas.

One of the first blows was the 1980 Mariel boat lift, during which 125,000 Cubans left for Miami after Castro announced Cuba would be well rid of all those who wanted to leave. Party members were ordered to stone the houses of those leaving and denounce them as gusanos, or worms. When Hector Maseda, who was an engineer in a prestigious scientific-research facility, argued that he had better things to do, he was expelled from the party and lost his job.

The corruption Farinas says he witnessed, both while in the Soviet Union and when he started work in a Havana hospital on his return, further eroded his faith in the system. After witnessing a senior party official pilfering sheets and powdered milk donated for sick children, Farinas was sent to prison for making false accusations. He had already been kicked out of the party for speaking out publicly about an act that also appalled many of his countrymen: the 1989 execution of Arnaldo Ochoa, a popular general convicted of drug smuggling, and three other senior army officers.

It is said to have been Raul Castro, who has held the post of defence minister longer than any counterpart in history, who orchestrated the executions of four of his own senior officers because of Ochoa’s political ambitions as a rival to his brother. The act reinforced Raul’s reputation as a hardliner and consolidated his own power. He is also the second secretary of the Communist party and effectively controls the interior ministry and all state-run media.

Increasingly disillusioned, Farinas started meeting other government opponents. But each group he associated with was broken by a wave of arrests. Most recently, this included a network of small independent lending libraries set up after Castro pronounced there were no prohibited books in Cuba — even though works by most Cuban exiles, Camus, Solzhenitsyn, George Orwell and many others are banned. Some of those who ran such libraries were among the 75 arrested in the most recent crackdown. Farinas slips out of his wheelchair and drags himself upstairs on his hands and knees, to show what remains of his own small library after a similar raid; the tatty collection of Spanish cultural magazines and scientific journals do not look like a threat to state security.

Then he and others started collecting signatures in support of a referendum on changes to Cuba’s communist system. The Varela Project has been trying to exploit a clause in the Cuban constitution that allows for discussion of new laws if at least 10,000 citizens request it. So far, more than 25,000 signatures in support of the project have been collected and presented to parliament. But the request has been ignored. Dozens of the project’s organisers were among those arrested in March 2003; many were convicted on the testimony of state security agents who infiltrated the dissident movement.

This is the history of political opposition in Cuba: groups are formed, infiltrated, members arrested and accused of conspiring with the US to bring down the government, which is enough to ensure the group is discredited to many Cubans. The level of infiltration makes even those within the groups mistrustful of each other.

In recent months, a dozen of the 75 arrested, whose health was failing, have been released — partly in response, it is believed, to overtures by the left-wing Spanish government. The EU has traditionally believed more was to be gained from a more moderate policy towards Cuba than the zealousness of the US, which Castro turns to his own advantage by painting himself as a plucky David to America’s Goliath. Following the arrest of the 75 dissidents, however, relations with most EU countries, including the UK, sank so low that all diplomatic ties were severed and are only now being slowly repaired.

Among those released was Marta Beatriz Roque, a long-term opposition figure who is calling for all of the island’s diverse dissident groups to attend a “grand assembly” in Havana in May. Few believe this will be allowed to go ahead. Another of those released was Manuel Vasquez, a journalist, prizewinning poet and former editor of a Communist-party youth magazine, who believes that another reason Cuba’s opposition is so fragmented is that “everyone wants to be a leader, not a soldier”. “There is no democratic tradition here,” says Vasquez, who was held in solitary confinement for 14 months and was only released because he was found to have a potentially fatal pulmonary embolism. “People here just don’t know how to defend their rights. This dictatorship is based on control of all means of communication.

“People, especially those in Europe with a more romantic idea of Cuba, need to realise we are in danger of passing from a communist to a military dictatorship,” says Vasquez, 53, sitting outside his dingy high-rise flat. Several days later, I learn the government has issued him an exit permit to leave Cuba. He looks certain to use it. But this also underlines another problem.

Half an hour’s drive north of Santa Clara is the downtrodden town of Placetas. The sign on the door of Berta Antunez’s wooden shack marks her out as a government opponent: a crude black-and-white painting of a prisoner behind bars. Antunez’s brother Jorge Luis Garcia has been in jail for the past 14 years for, initially, criticising Cuban foreign policy. Scribbled notes to his sister smuggled out of prison and since published abroad have highlighted the appalling conditions and brutality to which prisoners of conscience are regularly subjected in Cuba.

Antunez sums up one of the main problems she sees facing Cuba as “geographical fatalism”. She says: “We are so close to freedom across the Florida Straits, many people would rather leave the island than stay and fight for a better future here. If all those who put their energy into constructing small rafts to escape put it into trying to change things here, we might have had a change of government long ago.”

Turning a blind eye to the waves of balseros, or boat people, who risk death by attempting to flee the island in flimsy craft, has been used as a safety valve to avoid explosions of social unrest. During the most recent mass exodus, in 1994, when economic hardship was at its worst following the collapse of the Soviet Union, more than 30,000 tried to reach Florida on hastily constructed rafts. After the majority were intercepted by US coastguards and returned to the US naval base at Guantanamo Bay while the political implications of their admission to the US were debated, they were finally allowed to emigrate.

Rather than a flood of exiles wanting to return to Cuba once Castro goes, it is this prospect of an even greater exodus of those wanting to leave the island that has the US worried. If a successor regime allows would-be emigrants to cross

the Florida Straits unchecked, it could well be the US military that steps in to stop the flow.

The official mantra of the Cuban government is that life may be tough — owing principally, they argue, to the US embargo — but most people are content. Crime is low (police are everywhere); there are few beggars (ditto); nobody is starving (a UN report claims 17% of the population was undernourished by the end of the 1990s); and education and health care are good and free. There is little evidence of such contentment on the streets. Fifteen years after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the disappearance of the island’s indulgent sponsors in the Kremlin, Cuba’s economy is still in crisis. It has improved in recent years owing to trade deals with China, Venezuela and a growing number of European companies. But basic goods are still rationed. A family ration book allows one tube of toothpaste every three months, a bar of soap every two months, 5lb of rice, 2lb of beans, 1/2lb of coffee per person and six eggs — on an average monthly wage of less than £10. As a result, a black market flourishes and nearly everyone is forced to find unorthodox and illegal ways of surviving.

Unlike the gerontocracies that prevailed behind the Iron Curtain, however, Castro has recruited highly educated young economists into the ruling elite. Some believe they offer the best hope Cuba has of a peaceful transition to democracy. Others fear that a power struggle — between moderates who support more market-oriented reforms and hardliners who fear that too swift an opening up of the economy could lead to a Tiananmen Square-style revolt — will play into the hands of the military; Cuba has little record of compromise.

After a brief flirtation with market reforms led by moderates in the 1990s, the hardliners now hold sway. What limited private enterprise had been allowed has been severely curtailed. Cuba’s main industry is tourism, but the face of its tourist industry — like that of its leadership — is almost exclusively white. Apart from free health care and universal education, the elimination of racial discrimination has been trumpeted as one of the greatest achievements of the revolution. Yet there are many who view racial divisions on the island as a time bomb.

More than half of Cuba’s population is black or mulatto. They live in the island’s most dilapidated areas, make up a disproportionate share of the prison population and complain of constant police harassment. They are excluded from the “convertible peso” — the tourist currency — as most tourist-sector employees are white, and so they are invariably poorer. Simmering racial tension exploded briefly and was brutally repressed in April 2003, when the government decided to make an example of young blacks who attempted to hijack a ferry and force it to change course for the US. Three were executed. When riots broke out on the Malecon in Havana in protest, the demonstrators were dispersed by club-wielding security forces.

To keep a lid on such discontent, the authorities have swelled the neighbourhood spy system — the committees for the defence of the revolution (CDRs) . There are an estimated 15,000 watch posts in Havana alone. Parents also say that their children are being indoctrinated with ever more vehement “anti-imperialist” views. One display was of primary-school children laughing and whistling to each other as their teachers encouraged them to sit scrawling anti-American graffiti and swastikas on the pavement with chalk in front of the US-interests section on the Malecon. Behind the children were giant billboards carrying pictures of Iraqi prisoners being tortured by US soldiers in Iraq. The sign read “Fascists — Made in the USA”.

The billboards were erected in response to Christmas decorations put up by the US-interest section containing a large illuminated “75” in protest at the jailed political prisoners.

Far from such playground politics, in Havana’s gritty neighbourhood of Alamar, Cuban youths start talking openly about what they really want.

“I want to be able to afford to buy a drink and take a girl dancing in a club, and I can’t,” says one 17-year-old. “I want a pair of Nikes or Reeboks,” says another. “I want to be able to walk into a tourist hotel and not be stopped like I am a criminal,” says a third. “Here, tourists have more privileges than we do in our own country. It stinks.” “Here they’ll arrest you for nothing. We are not free to say what we want. I just want out,” says one 22-year-old, who has already tried to flee Cuba on a flimsy raft and says he will try again. None of them wishes to be identified.

“The climate of fear this regime plays on has been very effective. We are frozen in time. At the moment, there is no sign of a thaw,” said one prominent academic, who also wants to remain anonymous. “There is a great emptiness and disorientation in this society. People are searching for alternatives. But the government does not give alternatives any space to grow.”

Some turn to religion, to the growing number of evangelical sects, to Santeria — an Afro-Cuban form of voodoo — or to traditional Catholicism. Outsiders point to the Catholic Church as a potential force for change in Cuba, but within the country itself there is less optimism.

Father Jose Felix Perez, of Santa Rita Church in Havana’s Miramar district, says despite hopes that the Catholic Church would be given more space in society following the Pope’s visit to Cuba in 1998, “nothing has changed fundamentally. We are still not recognised as an interlocutor with the government. People here are spiritually exhausted. We all need to be able to look to the future, but people see a future with little hope”.

Every Sunday morning, a group of women dressed in white gathers for morning mass at the church of Santa Rita, among them Laura Pollan. All have husbands, fathers or sons among the 75 dissidents still in jail. They come to his church, Father Jose Felix says, because Santa Rita is the patron saint of difficult causes. But the church is also close to the embassy district of Havana and the women, calling themselves the damas en blanco (the women in white), hope such a high-profile location will draw attention to their campaign to have the political prisoners released.

After mass, these women walk silently up and down outside the church with pictures of their loved ones pinned to their clothes. They then stand before the church and say the Lord’s Prayer in unison. After praying, the women raise their hands and call loudly for what all but those who rule Cuba now desire: “Libertad!” — “Freedom!”

Passers-by pay them little attention. “Those who know what they are doing are afraid to show them any sign of support,” the priest says. “The problem for dissidents is one of solitude.”

“We will never give up our protest,” declares Pollan. “The authorities have three options — free our husbands, imprison us or kill us.” Sadly, there is a fourth: the women are ignored — not only by their countrymen but by the world.