June 11, 2006

June 11, 2006

Investigation

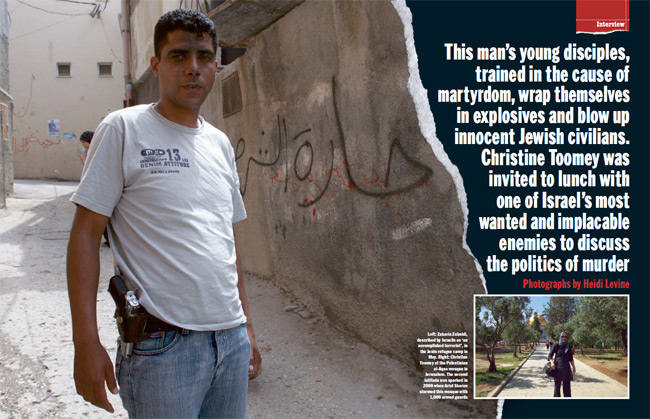

Christine Toomey was invited to lunch with one of Israel’s most wanted and implacable enemies, Zakaria Zubeidi, whose disciples are trained in the cause of martyrdom

The black cloud of minute shrapnel shard shrouding much of Zakaria Zubeidi’s face, including the whites of his eyes, is so surreal and sinister-looking that I am momentarily mesmerised as he approaches me to take a seat by my side for lunch.

Even before we start talking I unconsciously strain a little closer to make out the full extent of the disfigurement. When I realise I am staring and may cause offence, my eyes drop to waist level and I catch sight of the man on Israel’s list of most wanted terrorist suspects adjusting his belt before sitting down. There is a large revolver – a 9mm Smith & Wesson, I later learn – prominently tucked into the top of his jeans.

This is not someone, I remind myself, anyone would want to upset in a hurry. Suddenly I no longer feel hungry. “Just a little for me, please,” I whisper to the wife of our host, a neighbour of one of the safe houses used by this head of the al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade in the Jenin refugee camp on the Palestinian West Bank.

As far as the Israelis are concerned, this man is a chief strategist of suicide bombers in the camp they refer to as “the capital of suicide terrorism”. Over the past four years, according to Israeli government sources, at least 83 Israelis have been killed and 686 more wounded in suicide attacks for which the al-Aqsa brigades have claimed responsibility. But to those in Jenin, who call him simply by his first name, Zakaria is both a godfather of the Palestinian resistance movement and a Robin Hood figure to the poor. To the children of the camp, raised amid the gun culture of so many years of warfare, he is a cross between a superhero and a pied piper, a man they idolise and yearn to follow.

In seeking a rare interview with Zakaria I am fully expecting that, if he does agree to see me, the meeting will last only a few minutes. “Zakaria never stays in one place for long,” my interpreter warns me more than once. So when he does come, I constantly anticipate he will cut off our interview and leave. As the photographer

zooms in on his face, I motion her to back off again to avoid rankling him prematurely. This is much to the later chagrin of my editors.

Yet Zakaria seems relaxed. He is dressed in a much more casual manner than I’ve been led to expect. Instead of the usual combat gear, semiautomatic M-16 rifle and lines of ammunition strung across his chest, he is wearing Fila trainers, jeans and a cream-coloured T-shirt with the logo “13lbs of denim attitude” printed across the right breast. He is in a reflective mood and not only stays to finish lunch but, once the plates have been cleared away, eases his tall, lean frame back in an armchair to sip strong, sweet tea and carry on talking.

Just before he appears in the room, a tall, gaunt figure identifying himself only as “Ramsey” takes a position on a sofa opposite me. As we exchange greetings, I notice that Ramsey keeps eyeing the open door behind my back. I calculate that he must be some sort of scout making sure the coast is clear. But as we await the arrival of the man described by one prominent Israeli politician as an “accomplished and proud terrorist”, Ramsey seems happy to answer questions. So, if Zakaria is such a prime target, I ask, how is it he has not been arrested or assassinated in one of the Israeli security forces’ “targeted killing” operations?

“There have been intense campaigns to get him. But so far he has been lucky. The people who move around Zakaria are extremely intelligent and, up until now, no collaborator has managed to get into his circle,” Ramsey replies cautiously. “Usually the people who get killed have weaknesses,” he adds. “They love money or they love women.”

Yet Zakaria, just 29, clearly loves the latter. When he does slip behind me with feline agility a few minutes later, to be greeted by outstretched arms from Ramsey and our host, one of the first things he mentions is he has become a father for the second time. His son, aged two, now has a sister. And two years ago a 29-year-old Israeli woman, accused of being Zakaria’s girlfriend, was arrested and charged with “contact with a foreign agent in a time of war”. Both the woman, a former legal secretary called Tali Fahima, and Zakaria have denied their friendship was romantic. But the allegations stuck with the Israeli public, for whom the “Fahima affair” became a national scandal. As a result, Fahima, who openly boasted her admiration for the man “who does so much for his nation… yet cannot even remain in the same place for half an hour”, is still sitting in an Israeli jail.

Before speaking to me for the first time, Zakaria smiles to acknowledge congratulations on the birth of his daughter. Apart from his disturbing facial disfigurement – the result of fragments of shrapnel embedded in his flesh as he mishandled a bomb three years ago – I see that, when he smiles, he could be described as handsome. His smile bares a perfect set of teeth in a curiously symmetrical crescent moon, a feature that has led some to describe him as clownish. But Zakaria is no fool, despite his education being interrupted at an early age by a lengthy spell in prison for throwing stones and Molotov cocktails.

Unlike me, Zakaria has a healthy appetite. As we start to talk he tucks into a large plate of makloobeh – a mix of rice, roasted cauliflower and chicken flavoured with cinnamon, cumin and cardamom. He smothers dollops of yoghurt on top of the mix before spooning it into his mouth and chewing thoughtfully, considering each question before answering. For most of the hour we sit talking, he speaks in quiet, measured tones. He displays little emotion until he mentions the death of his mother, killed in the spring 2002 Israeli offensive against the refugee camp. The army raid followed a suicide bombing by a Jenin resident in which 29 Israelis died. As tanks rolled into the camp, hundreds of homes were reduced to rubble, leaving 2,000 Palestinians homeless. At the end of 10 days of fighting, 23 Israeli soldiers and 52 Palestinians, including women and children, were dead.

As the call to prayer echoes through the narrow, winding and still battle-scarred streets of Jenin, Zakaria talks about the special affinity he feels he has with its children, and the loss of childhood, including his own. He recalls being sent to a prison as a boy of 14 at the outbreak of the first intifada uprising against Israeli occupation. The previous year he had been shot in the leg by an Israeli soldier for throwing stones. Despite six months in hospital undergoing four operations, he was left with one leg shorter than the other and a slight limp that is still noticeable. “I had already been injured by soldiers, then I was sent to prison for six months; there they made me the representative of the other child prisoners and I started taking their problems to the head of the jail,” he explains. Soon after his release, he was sent back to jail; this time for 41/2 years for throwing Molotov cocktails.

“I was transferred from the child area to the adult area of the prison, and the adults dealt with me as a child. I could not absorb what was happening. In the children’s section I was looked upon as a leader. How could I be demoted to a child again after so much experience as a leader?” While in prison he was recruited to the ranks of Yasser Arafat’s Fatah movement. After he was released from jail in the wake of the 1993 Oslo peace accords, he joined the Palestinian Authority’s (PA) police force. But disillusioned by the PA’s nepotism and rife corruption, he soon left and got a job, briefly, as a construction worker in Tel Aviv. Arrested again for failing to possess a work permit, he was sent back to Jenin, where he took a job as a truck driver transporting flour and olive oil. He lost this job when the occupied territories were sealed off by the Israelis at the beginning of the second intifada in September 2000. It was after witnessing the killing of a close friend by Israeli soldiers the following year that he turned to armed militancy and bomb-making.

But it is what happened before he was jailed the first time as a child, and what happened after the outbreak of the latest intifada, to which Zakaria returns again and again. It is this that holds the key to the man he is today. It is here that his bitterness and buried pain lie. “I was injured at 13, put in jail at 14. Where is my childhood? Where has my childhood gone?” he repeats with self-pity. “Did you know we had a children’s theatre in the camp before that? Arabs and Israelis. They used to come to my house to practise,” he says with a sudden, sour laugh.

The theatre group he talks of was the initiative of an Israeli peace activist called Arna Mer-Khamis, who married a Palestinian and became a prominent human-rights campaigner. During the first intifada in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Israel closed all Palestinian schools in the occupied territories for a time, she started a series of learning centres for Palestinian children in the West Bank and Gaza. As part of an initiative to foster understanding between Palestinians and Israelis, she opened a children’s theatre in Jenin called Arna’s House, run by a group of dozens of Israeli volunteers. The rehearsal space for the theatre troupe was the top floor of Zakaria’s house. It had been offered by his mother, Samira, a widow struggling to raise eight children alone, who believed peace between the two warring sides was possible. Zakaria’s father had been an English teacher prevented from teaching by the Israelis because of his membership of Fatah. To support his family he became a labourer in an Israeli iron foundry until he died of cancer.

At the core of the troupe were six boys: Zakaria, then 12, his older brother Daoud, and four others around the same age. There was Ashraf, an extrovert who dreamt of becoming a professional actor; Yusuf, whom Zakaria described as “the most romantic and sentimental of all of us”; Yusuf’s neighbour and best friend, Nidal; and Ala’a, a withdrawn boy traumatised by the demolition of his home by Israeli forces as collective punishment for the actions of an older, jailed brother. Zakaria talks of the time he spent with the troupe as one of the happiest of his life. A time when the children “felt like real people, people who mattered”.

As the boys acted out their fantasies and frustrations in this room in Zakaria’s house, Arna’s son, the Israeli actor Juliano Mer-Khamis, started making a documentary about their lives. Over a decade later, following the 2002 Israeli incursion into Jenin, he returned to find out what had happened to the boys and complete his documentary, Arna’s Children, released in 2004 to critical acclaim. Zakaria was by then a member of the al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades. His brother Daoud had been sent to jail for 16 years for terrorist activity. The other four – Ashraf, Nidal, Ala’a and Yusuf – were all dead. Also dead was Zakaria’s mother, killed a month before the incursion, when Israeli forces had already started staging lightning raids on the camp. Samira had sought refuge in a neighbour’s home, but had briefly popped her head out of a window and was shot by an Israeli soldier and bled to death. Zakaria’s brother Taha was killed by Israeli soldiers shortly afterwards.

But it is not just the deaths of his mother, brother and friends that have embittered Zakaria. It is the deafening silence afterwards of those in Israel’s peace camp who he had thought were his friends. “Not one of those people who came to the camp and were our guests as part of the theatre group, fed every day by my mother, called to say they were sorry my family had died,” he says. “Not one of them picked up a phone.”

Perhaps I have not spent long enough with the Israeli families of those killed by suicide bombing attacks, although I have spent many hours sitting with them. But in these moments, before Zakaria adopts a more bravura performance, what I hear are the words of a still wounded child. “That is when we saw the real face of the left in Israel; the left who later joined the Sharon government,” Zakaria continues. “So anybody talking about the peace camp in Israel does not convince me. I have no more confidence in the left, and this is a scary development. When you lose hope, your options are limited,” he says with a deep sigh, slumping back in his chair again. “So this is how suicide attacks happen. When people lose hope. When a suicide bomber decides to carry out an attack, he’s fully convinced there is no more hope.”

“Look,” he says, “there is a war being waged against us on every front, including economic. What else can we do? How can we pit our strength against the power and military capabilities of the Israelis? How can we fight on the same level? If you use Apaches [helicopters] and F-16s [fighter jets] against me, of course I am going to use a suicide attack against you.”

As he fixes me with his gaze, I consciously try not to look away before he does, as a challenge to what he says. But he outstares me. So how can this bloody cycle of violence on both sides ever come to an end, I ask, fully expecting the pat answer he duly returns: “It will only end with the establishment of a Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital, and with making sure that Palestinians have their rights.”

Unlike the recent victors in the Palestinian election – the radical Islamic movement Hamas, which refuses to recognise the right of Israel to exist – those allied to Fatah, such as al-Aqsa, still support a two-state solution of an independent Palestine alongside the state of Israel. Within this context, the power and influence of extremists such as Zakaria cannot be overestimated. In the run-up to the election of Mahmoud Abbas as Palestinian president in early 2005, Abbas travelled to Jenin to pay court to Zakaria. When crowds chanted Zakaria’s name, not that of Abbas, as the gun-toting militant hoisted the 69-year-old former schoolteacher onto his shoulders to carry him through the streets, the message was not lost on the elderly politician. Even Arafat paid homage to the young firebrand, Zakaria recalls, once patting him on the back and saying: “Zakaria, buddy, I love you. We’re marching to Jerusalem!”

“Look,” Zakaria says. “Whoever thinks we can live under occupation is mistaken t-o-t-a-l-l-y,” drawing out the last word for emphasis. “We are present and we have the

right to live. Our children have the right to live, and if we feel we have come to the point where Palestinian children don’t have the right to live, then childhood and the whole concept of childhood in the world is finished.” So we return to childhood. But what about those whose childhood is cut short by Palestinian suicide-bombing atrocities, I badger him. And it is here our discussion enters the realm of fantasy. “I have not in all my resistance hurt a child. I am against hurting children. In the Aqsa-brigade suicide attacks never did a child die. Most of the acts I’ve been involved in are shooting acts,” insists the man sat before me with a gun at his hip.

Exactly what he has and has not been involved in should be a matter for the courts to decide. According to Israeli sources, at least six children have been killed and many more injured in suicide attacks for which al-Aqsa have claimed responsibility. Yet it will almost definitely never come to a court appearance. If Zakaria does not himself become a shahid, or martyr, as suicide bombers call themselves, he faces the near certainty that he will be targeted and killed by Israeli security forces, as have previous heads of the al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades.

Zakaria admits he does not expect to grow old and seems resigned to the prospect that his children will grow up without their father. There have been numerous attempts to assassinate him. One, by an elite unit of Israeli border police two years ago, left five Palestinians, including a 14-year-old boy, dead in a shoot-out. Soon after we meet, Israeli security operations are again stepped up throughout the West Bank. Nine Palestinians are killed close to Jenin and nearby Nablus, and Zakaria is again on the run.

When I dismiss his claim about avoiding child targets as nonsense, Zakaria starts to backtrack. When a suicide bomber walks into a shopping mall or cafe or onto a crowded bus and blows himself up, he is oblivious as to whether or not there are children among those he intends to murder, I insist. “When kids are targeted, that’s a mistake,” Zakaria blusters, before cranking his political posturing up a gear. “Every time we have a suicide attack it is a reaction to an aggressive Israeli attack. Our attacks are not strategic attacks. All the attacks of the Aqsa brigades have been reaction to big Israeli aggressive attacks. Since we all feel that we are targeted, we follow an Arabic saying, ‘Don’t die before showing you’re a strong opponent.’ We have no problem with Israel. We have a problem with the occupation. We in Palestine have the highest level of independence and integrity of thinking.”

From here our discussion descends to absurdity. When I challenge him about the fundamental barbarity of the act of suicide bombing and the waste of the young lives of the suicide bombers, he insists the al-Aqsa brigades have never used a child in attacks. The case of a 16-year-old boy who, four years ago, positioned himself alongside a group of elderly people playing chess before detonating the bomb he was carrying, killing himself and two others and wounding 40 more in an attack attributed to al-Aqsa is ignored. And what about even younger boys, I argue, caught at checkpoints with bomb belts strapped to their waists? “Ah yes,” Zakaria concedes. “But they were intending to be caught. rA true suicide bomber will never be stopped by any checkpoint. These boys you are talking about go to the checkpoint desiring to be caught to escape their bad economic situation. They want to go to prison – they can study better there.”

The idea that teenage suicide bombers are deliberately allowing themselves to be caught by the Israelis so they can get a bit of peace and quiet to do their schoolwork behind bars is clearly preposterous. But when I laugh out loud, Zakaria tries to drive the point home, gesticulating with his finger in the direction of my pen and notepad. “I would like you to know. Write it down! We do not use children for such acts.”

As the tension in the room rises, the curtain billows away from the window again to reveal the wide-eyed children gathered outside, clearly listening to what is going on inside. Glancing at the innocent faces pressed against the tilted glass slats at the window, Zakaria muses on his attraction to the children of the refugee camp.

“They like me because I can talk to them. I always come down to their level. They are proud to know me. Other kids will ask, ‘Do you know Zakaria?

Have you spoken to him?’ Kids look up to me as a fighter. I am a symbol of resistance. It is important they see I am not too big to pay attention to them, that I care about them. I want them to know Zakaria is easy to reach. Zakaria is there to speak to. These things make kids come near to you.”

So, pied piper? Manipulator of innocence? Terrorist? Wounded child? Resistance fighter? Superhero? To understand is in no way to excuse, but Zakaria Zakaria is no enigma. Following the arc of his life in this extraordinary encounter, I conclude it little wonder he is all of these.

Then, just as he had entered with no warning, little ceremony and children following in his wake, the man who has been compared to a cat with nine lives slinks quietly from the room.

Al-Aqsa Martyrs’ brigades

The al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades emerged at the start of the second intifada. The intifada was sparked by Palestinian outrage that Ariel Sharon and 1,000 armed guards had entered their holy site — the Haram al-Sharif, or “Noble Sanctuary” containing the al-Aqsa mosque — in east Jerusalem. The brigades consist of local clusters of armed activists believed to be affiliated with Fatah — the political organisation founded by Yasser Arafat that ruled the Palestinian Authority until Hamas won an overwhelming majority in January’s elections. Fatah leaders claim there is no supervisor-subordinate role between Fatah and al-Aqsa, and that they have never been able to exercise effective control of the martyrs’ brigades. Local al-Aqsa brigades are believed to be loosely structured and driven by charismatic personalities such as Zakaria Zubeidi. When I try to confirm with Israeli authorities the charges Zubeidi is wanted on, I am stonewalled. I am instructed to trawl through government records of 135 suicide and other bombing and shooting attacks carried out in Israel since September 2000 to see how many the al-Aqsa brigades have claimed responsibility for. Total: 20.

Theatre of war

In 1989 the Israeli peace activist Arna Mer-Khamis opened a children’s theatre group in Jenin called Arna’s House. Zakaria is one of the few members still alive

YusUf Sweitat

After graduating from high school, Yusuf became a homicide investigator with the Palestinian police. But in 2001, after witnessing the killing of a 12-year-old girl by an Israeli tank, he joined the Islamic Jihad extremists. At 22, after making a video of himself and a friend reading the Koran, the two drove into an Israeli town and opened fire, killing four, before being shot dead by Israeli police.

Ashraf Abu el-Haje

Ashraf joined the al-Aqsa brigades in early 2002. He and Yusuf’s cousin Nidal died at the age of 22, at the height of fighting during the Jenin incursion. They were killed by an Israeli helicopter missile after hacking out a hole to make a firing position in a wall of Zakaria’s house (the same room he and the other child actors used as a rehearsal space).

Ala’a Sabagh

After Arna’s theatre group disbanded, Ala’a dropped out of school and joined the al-Aqsa brigades. During the Jenin incursion he was captured by the Israelis. On his release, after giving a false name, he returned to Jenin and became head of the camp’s al-Aqsa brigade. In 2002 an Israeli aircraft fired a missile into the house he was hiding in with the leader of the Islamic Jihad. Both were killed.

Zakaria Zubeidi

Juliano Mer-Khamis, who made the documentary Arna’s Children, calls Zakaria “a charmer, who always took care of his appearance”. While few of those in Israel’s peace camp, hosted by Zakaria’s mother, took any interest in what happened to his family after she was killed, Mer-Khamis stayed in touch and is now founding a theatre in Jenin: www.thefreedomtheatre.org