June 7, 2009

June 7, 2009

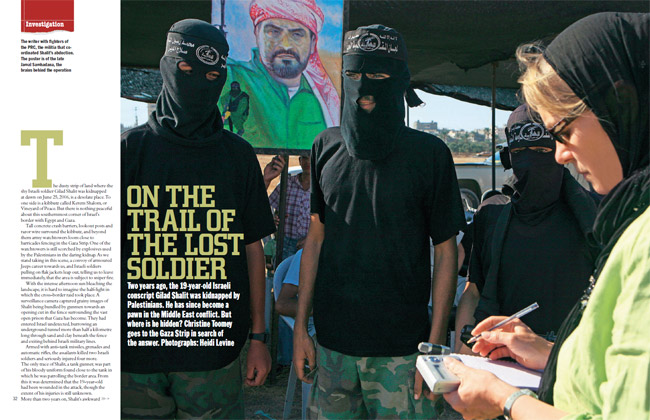

Investigation

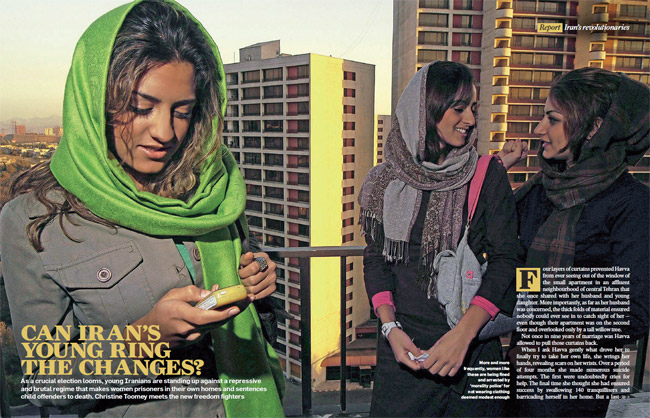

As a crucial election looms, young Iranians are once again standing up against a repressive and brutal regime

Four layers of curtains prevented Havva from ever seeing out of the window of the small apartment in an affluent neighbourhood of central Tehran that she once shared with her husband and young daughter. More importantly, as far as her husband was concerned, the thick folds of material ensured nobody could ever see in to catch sight of her — even though their apartment was on the second floor and overlooked only by a tall willow tree.

Not once in nine years of marriage was Havva allowed to pull those curtains back.

When I ask Havva gently what drove her to finally try to take her own life, she wrings her hands, revealing scars on her wrists. Over a period of four months she made numerous suicide attempts. The first were undoubtedly cries for help. The final time she thought she had ensured success by swallowing 140 tranquillisers and barricading herself in her home. But a last-minute call to a relative to say goodbye raised the alarm. Emergency services broke in, and she was rushed to hospital, where she remained on life support in a coma for several days. “There was no one incident that pushed me to do this, just very heavy pressure for a long time until I understood I couldn’t take it any longer,” says Havva, a strikingly beautiful 31-year-old who asks to be identified only by this pseudonym (meaning “Eve” in Farsi), since she comes from a rich and prominent Iranian family. “All my dreams were destroyed when I married at 17. There was no light, no hope in the way I was forced to live,” she says. She talks in a low voice of how she could never leave the house without her husband’s permission, nor make friends, work or resist him forcing himself on her several times a day. “But it is the traditional way. I thought that was all there was.”

Havva’s experience is far from unusual in modern-day Iran. Despite some advances in women’s rights over the past decade, and the fact that 60% of the country’s university graduates are now female, legally and socially women are still considered far inferior to men. In the words of the lawyer Shirin Ebadi, winner of the Nobel peace prize, “criminal laws adopted after the revolution took away a woman’s human identity and turned her into an incapable and mentally deranged second-class being”.

While deep discontent is felt at all levels of society, it is the women and young of Iran — 60% of Iran’s 70m population are under 30 — who are the most frustrated at the backward turn their country has taken in the past four years under Ahmadinejad’s fundamentalist administration. If this Friday’s presidential poll is truly open and democratic, which few believe it will be, their votes will be crucial in deciding the outcome, just as they were in propelling the reformist cleric Mohammad Khatami to power, twice, in landslide victories between 1997 and 2005. Khatami was prevented by a two-term limit from standing again in 2005, and it was then that Ahmadinejad, the ranting former mayor of Tehran and a religious zealot, took over the presidency. After throwing his clerical hat into the ring once more in the early stages of the current race, Khatami quickly withdrew, having reportedly been warned by the country’s ultra-conservative forces that he would suffer the same fate as Benazir Bhutto if he continued, leaving the opposition reformist camp fielding little-known candidates.

It was when Khatami was still in power that I last visited Iran, nearly 10 years ago. The light he let into this long-suppressed society by throwing open the country’s political curtains, if only partially, was refreshing. Though, even then, the conservative mullahs who opposed him, and who pull the real levers of power in Iran by controlling religious institutions that run parallel to and oversee every branch of government, saw to it that most of his reformist legislation was quashed. Hundreds of activists continued to be jailed and killed. But during his time in office, Khatami oversaw a brief flowering of civil society, advocated freedom of expression and promoted a series of legal reforms to the rights of women. These included giving women limited divorce rights, previously reserved only for men, and easing constraints on the Islamic dress code that had once made shedding the chador an offence punishable with prison and 74 lashes.

At that time there was an explosion of colour on the streets of the capital, with growing numbers of women throwing off the drab floor-length black cape in favour of knee-length coats and shoulder-length head coverings or bright headscarves. In the past four years, many women have gone back to wearing the chador, not out of piety, but out of self-protection as the country’s “morality police” are once more omnipresent, stopping, fining and arresting girls and women whose hijab is not “modest” enough, resulting in a police record potentially preventing them from getting a job or studying in future.

But during the easing of social constraints overseen by Khatami, Havva was finally able to divorce her husband. She has since acquired a psychology degree and supports herself and her 11-year-old daughter by working with an organisation that counsels young people on how to avoid depression. In recent years, the demand for such help has burgeoned beyond the capacity of Iran’s mental-healthcare professionals. Iran’s suicide rate, especially among women, is increasing, as is prostitution, alcoholism and gambling — though there are no reliable statistics on the prevalence of any of these as, officially, such problems do not exist.

The one serious social problem the government is unable to deny is drug abuse; Iran now has the highest rate of opiate addiction in the world. Ten years ago it was officially confirmed that there were 2m heroin and opium addicts in Iran, then equal to 2.8% of the adult population. This figure is thought by some to have now doubled.

“In a society where so much is prohibited, everything somehow becomes allowed,” says an Iranian expert on drug abuse. “As soon as a young person buys a forbidden pop CD or DVD of a western movie or banned alcohol on the black market, he or she comes into contact with an illegal underworld, and that is quickly exploited. I worry the moral decay in my country is increasing so rapidly that a point will be reached soon where it is very hard for us to turn back,” she adds. She, too, requests anonymity for fear of government reprisal for airing such pessimism.

In stark contrast to the cautious, but outspoken, optimism of some of those I met a decade ago, an atmosphere of extreme suspicion and paranoia now prevails in Iran. As I struggle on occasion to understand what people are trying to tell me, my interpreter explains that his countrymen have become used to talking in metaphors rather than saying clearly what they feel. “In Iran there is an expression that the walls have mice and the mice have ears,” says one young woman, meaning that Iran’s intelligence service is 70m strong — the country’s entire population.

Her black chador slips constantly down the back of her head and shoulders as we sit talking, revealing a bright silk Burberry headscarf knotted under her chin and an elaborate diamond brooch in the shape of a flower beneath her religious garb. “Please don’t take any photographs of me like this,” she asks politely of the photographer.

Eshraghi, 45, refuses to be drawn on her feelings about wearing the black veil, despite confessing in an interview with The New York Times six years ago that she hated wearing it and regretted the fact that the chador had been forced on women. “There must have been some mistake in the translation,” she says disingenuously. Voicing such views about a garment symbolic of the sacred is clearly more problematic in the current climate. When she spoke openly of her frustration at having to wear the chador — which she said she only did because of her family status — her husband was one of the most visible reformist politicians in the country, and his brother, Khatami, was president. As former head of the interior ministry’s youth department, Eshraghi has also been an influential figure in the reformist movement. But her outspoken criticism has led her more recently to be disqualified from running for parliament by the Council of Guardians — the powerful and deeply conservative body loyal to Iran’s current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, which vets, and can block, potential candidates.

Yet Eshraghi cannot contain herself when I ask what her grandfather would think of Iran’s present state of affairs. “Things would not be the same if he were still alive. I would talk to him and he would listen to me, as he always did,” she says, glancing across at a photograph in a cabinet of her daughter as a young girl curled up beside Ayatollah Khomeini, who died aged 86 in 1989. She implies her grandfather mellowed with age, astounding as that might sound to relatives of thousands of political prisoners he ordered killed in mass executions the year before he died. She says if Khomeini were still alive, he would have adjusted his views to take in some of the rapid changes of the past 20 years, especially the expectations of more freedom among the young.

In the lead-up to this month’s presidential election, a renewed government crackdown on those who oppose or challenge the ruling conservative forces has led to repeated waves of arbitrary arrests and harassment directed not only against women’s-rights activists, but also student leaders, trade unionists and human-rights workers. Even Shirin Ebadi’s Centre for the Defence of Human Rights was closed down six months ago because it allegedly “threatened national security”.

Dozens of women working on a controversial petition, the “One Million Signatures Campaign”, calling for equal legal rights for women, have landed in jail, some subject to 20 lashes, beatings and solitary confinement. One, Alieh Eghdam-Doust, is now serving a three-year sentence in Tehran’s feared Evin prison — notorious for torturing, raping and killing inmates. Most legal changes the campaign is seeking are rights women in the West take as given. These include equality in divorce (even the law amended under Khatami holds that a man can divorce his wife at will whereas a woman must prove her husband guilty of misconduct); more equality in child custody, normally granted to fathers after children reach the age of seven; and fairer inheritance legislation. Currently wives are entitled to only one-eighth of a husband’s estate when he dies, this to be shared between wives if the marriage is polygamous, the rest going to the children; daughters are only entitled to half of what sons inherit.

The petition also calls for the age at which a girl can be married to be raised from 13 to 18, and the age of criminal responsibility for girls to be raised from 9 to 18 (it’s 15 for boys). Iran is the only country in the world that still executes child offenders; one young woman, 22-year-old Delara Darabi, was hanged in early May, while her appeal was still being heard, for a murder she vehemently denies having committed at 17. The petition also calls for honour killings, the stoning to death of women for adultery and polygamy to be banned, and the wearing of the hijab to be a personal choice.

“I don’t think anyone should be arrested for what they believe in,” says Eshraghi, who has also signed the petition. “You may live in paradise, but if you’re not free you have nothing.”

Among those who’ve paid for supporting the campaign is Parvin Ardalan, one of its founders. She was held in solitary confinement at Evin prison after being charged with threatening national security with her work on the petition. She is appealing against three separate jail sentences, totalling more than three years, on related charges. “We’re challenging the status quo, and as far as the government is concerned that threatens national security. If these laws are changed then Iranian society will change fundamentally,” she says. But one lawyer supporting some of those jailed goes further, explaining the authorities justify their crackdown by claiming the campaign is a front for foreign intervention: “They still do not believe this is a domestic, grass-roots movement. They accuse us of instigating a ‘velvet revolution’ and say we’re under the influence of foreign countries trying to subvert the regime.” In recent years the campaign has opened branches in Europe and the US to collect signatures from Iranian women living abroad, which, she argues, “hardly constitutes subversive activity”.

“At the heart of this is the fact that if women are given equal rights, it will open the way for more democracy in this country, and those who oppose women’s rights here in Iran oppose democracy,” says Narges Mohammadi, vice-president of Shirin Ebadi’s now-banned Centre for the Defence of Human Rights. “But people, especially women and the young, are now so fed up with the constraints and injustices they face, I believe we’re near to a tipping point, and if changes don’t come soon, Iran will face a very serious crisis.”

Two days after we sit talking in Mohammadi’s office she is stopped trying to board a plane to attend a Nobel-committee peace conference for women in Guatemala. Her passport is confiscated and she is forbidden from further travel abroad.

Another of those who have had their passport confiscated in recent months is the former student spokesman Saeed Razavi-Faqih, charged in absentia while studying in France with “propaganda activities against the system” for posting comments critical of the regime on internet sites. He has also been jailed in the past in Evin prison for alleged “subversive activity”. Razavi-Faqih fears, despite widespread discontent, that the turnout in a country where more than 50% routinely vote may not be high enough in the coming elections to oust Ahmadinejad: “Coverage of the election in the state-controlled media has been very low-key. It’s not in the government’s interest to promote a high turnout, because low numbers of voters favour Ahmadinejad and his fanatical support base, who’ll vote no matter what. I fear when Khatami left the race we lost the game. The other opposition candidates are so uninspiring. They are out of touch with the young.”

It is only in the past two weeks that opposition candidates have been allowed access to state media to put their message across. In an effort to reach out to the young, some have tried garnering support by posting speeches and slideshows on Facebook. But even though more than 20m Iranians have access to the internet, the regularity with which government censors block sites means access to such messages is patchy.

Leading opposition candidates have also struggled to show they represent a break with the past. The opposition frontrunner Mir-Hossein Moussavi was last active in politics 20 years ago when he served as prime minister during the devastating 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war; he was then considered a hardliner, and he only looks like a reformer now compared with the fanatical Ahmadinejad. The track record of the reformist cleric Mehdi Karroubi, another opposition candidate, is hardly more inspiring. A former speaker of the parliament, he is best remembered by the older generation as the former head of the Martyrs Foundation in the wake of the revolution, making him particularly hated by many exiles for the part the foundation played in the mass expropriation of private property. Karroubi also failed to beat Ahmadinejad when he ran for president in the last election. When I meet Karroubi, he is keen to expound on one of his newly favourite themes: women’s rights. In an attempt to win the crucial female vote, he has been promising to pay more attention to the concerns of women, and vows he will be the first president to appoint a female member to the cabinet if he wins. The meeting is pointedly held at the Research Institute for Enhancing Women’s Lives. Karroubi strokes his white beard when asked what specific changes he would make to the laws concerning women’s rights, and answers vaguely that he has “always had an open mind when it comes to women’s affairs”. He only becomes animated when I raise the thorny issue of polygamy, which, though culturally alien to the majority of Iranians, Ahmadinejad’s administration has been quietly promoting; 67 of 290 members of the country’s parliament, the majlis, are understood to have more than one wife. “They try to keep this secret, which shows they are ashamed of it,” says Karroubi, condemning polygamy as “little more than legalised sexual relationships”.

One heroine of the revolution who considered running for president herself in this election is the former vice-president to Khatami, Massoumeh Ebtekar. She was once the radical mouthpiece of students who stormed the American embassy in Tehran in 1979, seizing 52 diplomats and holding them hostage for more than a year. The last time I met her, she was reticent and guarded. This time she is outspoken in her condemnation of the current regime’s “Taliban-like policies of wanting to keep women in the home”. Ebtekar, who supports Moussavi, does not rule out running for president in future; although the constitution does not explicitly exclude a woman running, some doubt whether the Council of Guardians would approve of it. But she says her priority now is to promote rather than dilute the opposition, and she wants to animate the young to vote, though she offers few fresh ideas on how to do this. “We need major change in the political and economic direction of this country,” she says, in her office in Tehran city hall, where she is now a city councillor. “We need more freedom of the press, more freedom for opposition parties…” At this her chador-clad assistant gesticulates firmly that my time is up and I am ushered out, reminded that, regardless of the outcome of this week’s vote, real power in Iran will continue to rest in the hands of the country’s conservative clerical regime.

Ahmadinejad’s populist economic policies, the reason he was elected in the first place, have led to soaring inflation. Unemployment has risen rapidly, and Iran’s economy has been hit hard by the oil-price crash, which has curtailed the spree of state hand-outs that Ahmadinejad built his popularity on, and on which Iran’s ruling mullahs who support him have relied. The country is still shackled by multiple sanctions, the latest imposed for its failure to halt its uranium-enrichment programme. Despite overtures by President Barack Obama to engage in talks, few expect international relations with Iran to be normalised any time soon.

“Iran’s economy is now teetering on the brink of disaster,” says Leylaz, who is allied to Moussavi’s election campaign. “We will have difficult times no matter who is elected. But if Ahmadinejad is re-elected we will be heading off the edge of a cliff.”

At first glance there is little evidence that the capital’s youth feel a sense of impending disaster as they stand chatting and laughing outside the bars and ice-cream parlours that line one of the main roads of Sa’adat Abad, a middle-class district in northwest Tehran. Even though they are just a stone’s throw from Evin prison, some daring young women risk arrest by donning skintight jackets, instead of chadors, and headscarves that reveal shocks of bleached hair. When a patrol car of morality police order two teenage girls dressed this way to sit in the back while a charge sheet against them is drawn up, they try to look nonchalant, and wave across at friends, smiling. Other cars full of teenage boys and young men cruise past the patrol unit, with some male passengers shouting out their names and phone numbers to girls on the pavement. This is speed-dating Tehran-style. Mixed-sex socialising and parties outside the family are formally forbidden. But they take place behind the scenes, many arranged in such ad hoc street exchanges.

When I speak to young people, they’re nervous at first and unwilling to give personal details. But when I ask them if they’ll be voting in this week’s elections their answer is a unanimous “100% yes”.

“I believe there will be a last-minute rush to vote,” says Faraz, 23, an engineering student. “Freedom is the key issue. People don’t feel secure when they go out on the streets. They’re afraid they’ll get arrested, particularly the young. We want change. We want to feel hope for the future, and to have a good time. We want this to be a good country to live in, where the government cares about what’s happening.”

As one young doctor confessed to me, “The problem with Iran is the bowl here is often hotter than the stew.” That is, too little attention is paid to domestic problems and too much to matters outside the country — such as funding terrorism and international posturing by Ahmadinejad against his nemesis, the USA, “the Great Satan”.

“But we have to be optimistic. We have to believe change is possible,” says Hannaneh, 20, a shy trainee teacher. “Anything is better than this.”

As she and her friends turn to walk away, I find myself fervently hoping their generation gets the chance to throw Iran’s curtains wide open.