January 28, 2007

January 28, 2007

Travel and Comment

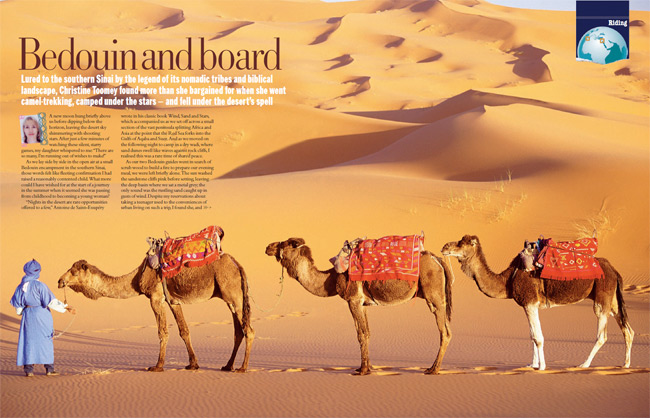

Lured to the southern Sinai by the legend of its nomadic tribes and biblical landscape, Christine Toomey found more than she bargained for when she went camel-trekking, camped under the stars and fell under the desert’s spell

A new moon hung briefly above us before dipping below the horizon, leaving the desert sky shimmering with shooting stars. After just a few minutes of watching these silent, starry games, my daughter whispered to me: “There are so many, I’m running out of wishes to make!”

As we lay side by side in the open air at a small Bedouin encampment in the southern Sinai, those words felt like fleeting confirmation I had raised a reasonably contented child. What more could I have wished for at the start of a journey in the summer when it seemed she was passing from childhood to becoming a young woman?

“Nights in the desert are rare opportunities offered to a few,” Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote in his classic book Wind, Sand and Stars, which accompanied us as we set off across a small section of the vast peninsula splitting Africa and Asia at the point that the Red Sea forks into the Gulfs of Aqaba and Suez. And as we moved on the following night to camp in a dry wadi, where sand dunes swell like waves against rock cliffs, I realised this was a rare time of shared peace.

As our two Bedouin guides went in search of scrub wood to build a fire to prepare our evening meal, we were left briefly alone. The sun washed the sandstone cliffs pink before setting, leaving the deep basin where we sat a metal grey; the only sound was the rustling sand caught up in gusts of wind. Despite my reservations about taking a teenager used to the conveniences of urban living on such a trip, I found she, and I, fell quickly into a desert mindset. When we were set the task of keeping the spot where we were bedding down for the night lit, we both set about trying to imitate our Bedouin guides in building improvised storm lanterns, cutting empty water bottles in half, partially filling them with sand and sticking in a lit candle before replacing the top to protect the flame.

- Bedouin and nomads

At the very start of our trip we had packed up our sleeping bags at 3am to climb to the 2,285-metre summit of Mount Sinai – the mountain where Christians, Muslims and Jews believe that God delivered his Ten Commandments to Moses. Starting the ascent in the middle of the night meant we would reach the summit to watch dawn break over the furthest reaches of the southern Sinai’s jagged mountain ranges. Since the guidebooks had described the climb as “easy except at the summit”, walking seemed a safer prospect than getting on a camel for the first time, in the dark, to go up a mountain.

But while my daughter had loped ahead like a gazelle, my extra years made the climb more of a challenge, especially the 750 rocky and uneven steps that scale the last section to its peak. Resting in the shade of St Catherine’s monastery, built on the slope of the mountain at the site of what was believed to be the biblical burning bush, I was only thankful we had not attempted the alternative, more difficult, route to the top: a towering ladder of 3,750 rocky stairs called the Steps of Repentance, hewn out of the mountain by one of the early monks as a form of penance.

When such reflections on the passage of time and mortality hit home, Saint-Exupéry is good company. Wind, Sand and Stars, after which the company that had arranged our trip was named, is the French pilot’s account of how he survived a near-fatal crash in the Libyan desert in 1935, and contains a moving, detailed account of what it feels like to be on the point of death. As we set out across the Sinai’s eastern sandstone desert on camels, with August temperatures nudging 50C, I can begin to imagine what that might feel like.

Most of those who travel with Wind, Sand & Stars, which supports environmental projects that encourage traditional Bedouin ways of life, plan their trips in spring, autumn and winter, when desert life is more manageable. But even then this is a harsh environment: temperatures can sink as low as -10C at night, and every aspect of life is geared to survival.

As a result, many Bedouin have long since abandoned their traditional ways, explain our guides, A’id, who is from the southern Sinai’s largest Mizayna tribe, and Zaid, from the smaller Jabaliyya tribe. While we sit around the campfire, drinking sweet mint tea with a delicious meal of rice, lamb, salad and watermelon, they talk of how increasing numbers of the estimated 25,000-40,000 Bedouin from disparate tribes in the southern Sinai have succumbed to the lure of an easier life on the coast. This is encouraged by the Egyptian government, which, frustrated with their itinerant ways, offers the Bedouin permanent housing, with running water, electricity and education for their children. All of A’id’s children, for instance, now live on the strip of coast facing the Gulf of Aqaba, as does he for much of the summer. But when the temperatures start to drop in autumn, A’id says he still feels the strong pull to return to the desert, wandering for weeks with his camels.

Most of the men’s tales revolve around food and water. First they trace the arc of the Milky Way, explaining that here it is known as the “fruit path” because, at its brightest in these parts in July and August, it marks the time when the precious crops of figs and mulberries grown close to the oasis can be harvested. Then they tell the story of the Thoria star that disappears and reappears around late May, which is taken as a sign by wild camels to return to their familiar watering holes before their humps shrink.

When we prepare to bed down for the night, the two men roll out their blankets a discreet distance from ours, and laugh as we fret that we might find a scorpion or snake in our sleeping bags. Scorpions hold no fear for the Bedouin. One of the few traditional customs most Bedouin women still observe in the days after giving birth, they say, is to boil one of the creatures, dry and crush it, then spread the powder around their nipples before their babies suckle, to help their newborn develop a resistance to scorpion venom.

Writing this in London, such a custom seems less reassuring than it did when I was crouched by a campfire in the Sinai. But then I open Saint-Exupéry’s memoir and sand trickles from its pages, and I remember feeling that many extraordinary things seem possible in the desert – not least the realisation that everything that matters is in front of your eyes in that very moment.