June 8, 2008

June 8, 2008

Investigation

All across Europe companies have been told to put more women in the driving seat, or be penalised. The ruling has been a huge success — but what does it say about sexual equality? Photographs by Lars Bech

Ansgar Gabrielsen’s voice echoes across the lobby of Norway’s Stortinget parliament as he shouts to a passing female politician.

“Am I a feminist?” he booms, letting out a deep rumbling laugh.

“You are!” teases the woman, who is wearing a red jacket and is in too much of a hurry to stop and discuss what he’s done to earn her approval.

“Really, I’m not,” Gabrielsen insists conspiratorially, lowering his voice and leaning closer to me as if he is sharing a confidence that he would rather not broadcast.

“You could say that I’m the opposite – a man, a conservative and I come from Mandal,” he explains, as if his place of birth disqualifies him from being a champion of women’s rights. Mandal is a small town in the far south of Norway, which is the country’s Bible belt, and Gabrielsen is a Pentecostal Christian, a bearish man, a former government minister and an archetypal alpha-male businessman.

But we are sitting in the Stortinget to discuss what Gabrielsen calls the “shock bombing” of Norway. As he tells it, the explosive formula was cooked up during a secret meeting, just six months into his job as minister for trade and industry, in association with one of the country’s most senior political correspondents. Gabrielsen had bumped into Alf Bjarne Johnsen of Norway’s biggest-selling daily newspaper, Verdens Gang (“The Way of the World”), or VG, in February 2002, and on the spur of the moment, he offered the veteran journalist the biggest story of his career if he would come to his office to meet with him within the hour.

The next day the people of Norway woke up to front-page headlines that rocked the nation: tycoons blanched, boardrooms rumbled and Gabrielsen’s fellow cabinet colleagues gasped in surprise and shock – he hadn’t deemed it necessary to include the government in his plans.

What the VG front-page story said, under the banner headline “Sick and Tired of the Old Men’s Club!”, was basically this: women would be wearing the trousers in future. The story listed the country’s leading companies with only men at the top of them. Out of 611 companies, 470 did not have one female board member. Little more than 6% of all the board positions were occupied by women.

Gabrielsen, the paper reported, was not just about to lift the glass lid on the meritocracy – he was smashing it with his meaty government fist and with all the force of the law.

Hundreds of men would be gradually removed from their positions as company directors and replaced by women. A new global record in business management would be achieved by making sure that 40% of all boardroom positions in companies listed on the Oslo stock exchange would be held by women within five years. If companies did not comply, the minister warned, he would introduce legislation and they would be prosecuted.

His cabinet colleagues, the then-prime minister Kjell Magne Bondevik and his centre-right coalition government, even Gabrielsen’s own Conservative party, must have choked on their breakfast bran. The ebullient minister had consulted none of them beforehand.

“If I had told them before, the initiative would have been killed by one committee after another,” he says. “No, I had to employ terrorist tactics. Sometimes you have to create an earthquake, a tsunami, to get things to change,” he says, laughing at his own daring. “If a left-wing feminist had come out with something like that it would have been dismissed as just another scream in the night,” he continues. “But because I said it, I knew that people would take notice.”

The fallout was instant. Business leaders and employers warned of dire consequences: a decrease in company competence, plunging shareholder confidence and a flight of foreign capital were just the immediate pinstripe reactions. Little short of financial Armageddon was forecast – the prospect of high heels kicking the chairs from under the men who dominated boardrooms would create economic meltdown.

But Gabrielsen had his finger on Norway’s pulse. The public mood in this traditionally liberal society didn’t just warm to the plan, it embraced it with a passion. Bondevik’s coalition government had no choice but to bow to public opinion and back the proposal. It decreed that state-owned enterprises would have just one year to meet the target, the deadline being January 2003. Private companies were given a period of grace of two years – until July 2005 – to increase the number of women on boards

to near parity with men. To reinforce the message, a draconian measure was held over their heads. If companies failed to meet this target, they would face closure.

By the government’s deadline of 2005, the percentage of women on company boards had quadrupled to 24%, which was still short of the target of 40%, so legislation was drafted. Companies had until January of this year to get their houses in order – or else.

This spring the government announced full compliance, even in the most intransigent sectors of banking and financial services. Between 560 and 600 women had been voted onto company boards. Hundreds of male board members were axed, although a small number of companies complied merely by expanding the size of their boards to avoid losing male directors.

It is now six years since Gabrielsen’s “shock bombing”, and the sky has not fallen in as predicted on this Scandinavian country, which is ranked year after year by the United Nations as the best place in the world to live, and last year was ranked the most peaceful by the Economist Intelligence Unit. It is too early to assess the real impact on the bottom line of the companies affected. The evidence that does exist, however, suggests that Gabrielsen’s plan had merit

beyond the politics of equality. A survey of the colleagues of women newly appointed to board positions showed that most of them have significantly higher educational and professional qualifications than many of the male colleagues they replaced, or sit next to. The women are not only brighter, they are younger, and the majority have distinguished themselves in a wide variety of other professional careers before being appointed to company boards.

This, says Gabrielsen, was exactly what he intended. He was not driven by ideology aimed at creating equality between the sexes, he says, despite accusations that the quota law was created by “fetishists of diversity”. The boardroom revolution he ushered in was inspired by studies in the United States showing that the more women there are at the top of a company, the better it performs. The move also made sound national economic sense.

“What’s the point in pouring a fortune into educating girls, and then watching them exceed boys at almost every level, if, when it comes to appointing business leaders in top companies, these are drawn from just half the population – friends who have been recruited on fishing and hunting trips or from within a small circle of acquaintances?” he says. “It’s all about tapping into valuable under-utilised resources.”

) ) ) ) )

Sceptics will argue that such a social and business revolution could only be achieved in traditionally egalitarian societies such as those within Scandinavian countries – and especially in oil-rich Norway with a welfare system offering generous support for working women.Norway is not typical of most countries. Until the discovery of huge gas and oil deposits in the North Sea in the 1960s, it was one of the poorest countries in Europe – a nation of farmers and fishermen. With husbands so often away at sea, Norwegian women became heads of the family, so equality between the sexes is deeply ingrained.

Women have long matched men in politics too. After Gro Harlem Brundtland became the country’s first female prime minister in 1981, 8 out of her 18 cabinet ministers were women. Every cabinet since has maintained roughly the same balance. The country has also enforced the 40% quota on all public committees for more than 20 years, and the internal rules of nearly all its political parties require an equal mix of men and women on electoral lists.

Now, as one of the world’s leading oil exporters, Norway registers an enormous budget surplus every year. This funds a generous welfare state for its small population of 4.7m, with benefits that are the envy of working parents everywhere. Free childcare is widely available. Maternity leave on full pay lasts a year – fathers get six weeks “papa leave” – and women are allowed to return home for one or two hours in the middle of a working day to breast-feed.

The Gabrielsen initiative was already pushing on an open door – but would it work elsewhere? Cue Spain. It has also now passed a similar law. Companies must give 4 out of 10 board positions to women within seven years. In Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s centre-right government is moving in the same direction, the first step being a “voluntary charter” committed to gender equality, and the Netherlands is pledging the same commitment to putting women in charge at the top.

And it’s not just in business that the barriers are being stormed by women. The move in traditional Spain was dismissed by many as another political ploy by the country’s wily socialist prime minister, Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero, to curry favour with the electorate. But his female-friendly initiatives have caught the national mood. He recently unveiled a new cabinet with more female than male ministers – including a heavily pregnant minister of defence.

The British cabinet fields just 6 women to 16 men and, though public opinion might favour action to address the imbalance, the evidence suggests that it is women themselves who might oppose it. When David Cameron suggested this year that he would operate a quota of women cabinet ministers to address the gender imbalance, some of the most vehement objections came from female colleagues. The former Conservative minister Ann Widdecombe said she would be “grossly insulted” if she were given a front-bench position on those terms. She is by no means alone in her opposition.

As far as many women are concerned, the idea that they might be chosen for any job on the basis of gender alone is galling.

“There is no appetite for quotas here,” says Jacey Graham, co-director of a FTSE-100 cross-company mentoring programme for women and the author of a recently published book on women in boardrooms in Britain. “There is an appetite to facilitate talented women coming through, but they must be seen to compete on the same terms as male colleagues.”

It is a view shared by business leaders.

“I agree completely that we don’t have enough women on boards, but I think the problem is much more deep-seated than that – it is that companies are not ensuring sufficient numbers of women are coming through their structures into senior management and executive positions from which they can break through the glass ceiling and into boardrooms,” says Sir Richard Evans, chairman of United Utilities. “The biggest assets of most businesses are their human capital, so what on earth can the argument be for not treating all those assets in the same way?

“But getting the best out of all the human capital begins in schools and universities, at the stage of careers advice and, later, advancement in the workplace. A big culture change is required to tackle that, and I do not necessarily believe changing the law changes people’s attitudes.”

Anna Dugdale, board director of the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and one of the few female financial advisers to a big NHS teaching trust, goes further: “I think a quota law would be the worst thing possible for women. You would never know if you were there on your own merit or owing to some legal requirement.”

But back in Norway, the “tokenism or talent” debate has already been consigned to history. Women just picked up the baton and ran with it.

) ) ) ) )

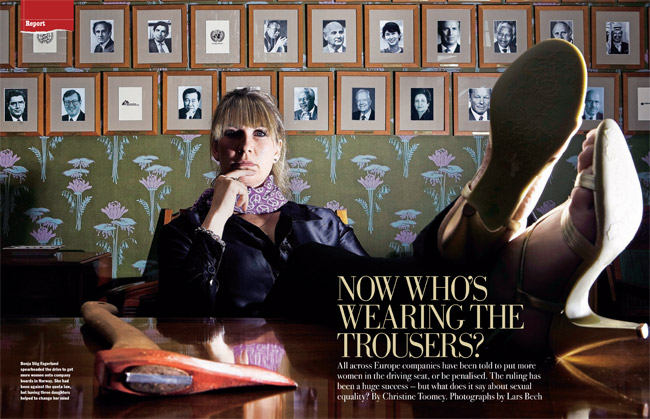

Benja Stig Fagerland is a figure straight out of Norse mythology. Over 6ft tall, she is a beautiful blonde who projects strength and intellect. A Dane who moved to Norway 16 years ago, she has been in the forefront of the female raiding parties who have stormed and conquered the male strongholds of the old order.

The 37-year-old economist with two degrees, an MBA, and three daughters aged 7, 4 and 1, penned an impassioned letter to one of Norway’s leading business magazines after Gabrielsen’s bombshell. It didn’t matter whether you were for or against quotas, she said. That argument was irrelevant and outdated. What was needed was more women in positions of power. In fact, Stig Fagerland had always been against quotas.

“I was young. I was clever. I was competitive and I believed I could do whatever I wanted to do without anybody’s help,” she says, sipping a large mug of coffee in her immaculate home in Oslo’s exclusive residential enclave of Nesoya.

She had been working for a business-software company and, together with a group of friends, had set up a network of young executives in their late-twenties and early-thirties called Raw Material. “We were like the winning team, a little arrogant, and determined to fight the old Scandinavian attitude of Janteloven – never believing you are better than anyone else. We wanted to get to the top.” But when her first daughter was born she realised that it was not just a question of relying on talent. “I began to see it was not that easy,” she says, “that was not how the world worked.” In fact, a survey commissioned by the British government in 2007 found mothers face more discrimination at work in this country than any other group.

After her letter was published, Stig Fagerland was contacted by Norway’s equivalent of the Confederation of British Industry, the Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise or NHO, and asked to spearhead the drive to get more women onto company boards. Since the NHO is one of Norway’s most traditional and conservative organisations, long opposed to the idea of quotas for women, she hesitated before accepting the challenge, afraid that the appointment might be little more than window dressing. Once in the post, however, she set up a project called Female Future, and invited companies to go “pearl diving” for women within their ranks who had talent that had not been fully utilised by the firm and whose potential could be nurtured, an initiative that made the issue of quotas redundant.

“This was an extremely important exercise as it got companies to focus on talent regardless of gender,” says Stig Fagerland, who now runs her own consultancy company that is aimed at empowering talent. Once these “pearls” were identified, they were put forward by their companies for training by Female Future. She believes that she also identified a key obstacle women face in rising through the ranks: “They don’t sell themselves in the same way men do.”

Part of the training programme she ran for the next two years involved teaching women how to do just that. “If you bump into your CEO in a lift and he asks you who you are, you need to be able to sum yourself up in 20 seconds; be honest, not over-modest,” she says. The project also set up a database of experienced businesswomen, which companies could tap into when looking for potential board members. “They could no longer claim that female candidates for these top positions didn’t exist just because they didn’t meet them in their private male clubs. We listed hundreds of strong, keen women who wanted these positions of responsibility.”

Of the 600 businesswomen who have taken part in the programme since it started, 300 now occupy board positions. “As an employer’s organisation, although we wanted more women in senior positions, we were against the quota law from day one, believing such decisions were entirely up to shareholders,” says Sigrun Vageng, an executive director of the NHO. “We thought that the threat of closing companies if they did not comply was quite ridiculous. But now we have to acknowledge that it is only because of the law and the public debate it provoked that real change has happened.”

“There’s no going back,” says Kjell Erik Oie, the country’s state secretary for equality and children. “We’ve realised it’s good for business.”

Like Gabrielsen, he refers to American research showing companies with the most women in top positions return higher profits than those with the least number of female directors. One study last year by the influential New York think-tank Catalyst, which ranked hundreds of Fortune-500 companies by the percentage of women on the board, found the top quarter outperformed those in the bottom quarter with a 53% higher return on equity. While another 2007 report, by the international management consultants McKinsey, looked at 89 top European companies and found those where women were most strongly represented on both the board and at senior-management level outperformed others in their sector in return on equity and stock-price growth.

Some argue that this is because those companies with a less traditionally male boardroom are more likely to be innovative and forward-looking. That, says Oie, is precisely the point. But are Norway’s top tycoons convinced about this?

) ) ) ) )

The man in the photograph Verdens Gang chose to illustrate the front-page story of Gabrielsen’s attack on “The Old Men’s Club” is a hard-nosed former fisherman turned billionaire. Kjell Inge Rokke is sometimes referred to as Norway’s Donald Trump. He once famously said his education was in “the university of the gutters”. After leaving school he went to work on long-distance trawlers in Alaska before returning to Norway, buying and restructuring companies and then rising to take control of the country’s leading industrial conglomerate. Aker is Norway’s largest private employer, with more than 27,000 employees in 35 countries and annual revenue in excess of £6 billion. It is the parent company for eight stock-exchange-listed firms in the traditionally male bastions of oil-drilling, shipbuilding and construction. Until 2004, Aker had no women on its board of directors, and in the words of one of its former presidents, it was a “club”, selecting new board members on the basis of “you put me on yours and I’ll put you on mine”.

When the 40% quota was proposed, Rokke opposed it, saying such decisions should be left solely to shareholders. Just how much things have changed since then is spread before me when I visit the company’s headquarters on the banks of an Oslo fjord.

Fanned out on the table are pictures of the current board members in both Aker and its subsidiary companies; out of 48 directors there are now 20 women. Yet this is clearly uncomfortable territory for Aker’s executive vice-president Geir Arne Drangeid. He is tense when we meet to talk about the conglomerate’s boardroom transformations. I’m at a loss to understand why until he concludes our meeting with the aside that he hopes the reason he was not re-elected recently for the board of one of Aker’s subsidiary companies was to make way for a woman.

Talking later to one of the Aker’s most senior former board directors, Kjeld Rimberg, the extent of the company’s initial opposition to the move becomes clear. “The view was that it was a political manoeuvre to pay lip service to feminists and had nothing whatsoever to do with the way companies were run,” he comments.

Seeing the writing was already on the wall, Rimberg says he told Rokke not to hesitate in asking him to stand aside in favour of a woman –which his boss promptly did.

“I did not take it personally. I consider myself lucky to have been invited to the party for 20 years,” says the former head of Norway’s state railway system. “After all, men have been protecting their power for years and years, and there are a lot of stupid and incompetent men on company boards.” It might have been because he was talking to me on the phone from a beach in the south of France that Rimberg finishes our conversation by saying that he is now feeling “quite relaxed” about the new law.

Among the women Aker has recruited to its board are two former government ministers: Kristin Krohn Devold and Hanne Harlem, sister of the country’s one-time prime minister. When Devold was defence minister, she says she was used to chauvinistic treatment on government trips abroad; in Italy it was assumed she was an assistant and she was asked if her group would like coffee. “But if women can hold positions in the most important boardroom in any country, its cabinet,” she says, “then they can certainly contribute to the running of a company.”

Women are more intuitive and sensitive to potential problems such as divided interests in boardrooms, says Devold. Hanne Harlem, a former justice minister, agrees with this sentiment and goes further: “Women are much clearer when it comes to ethical issues. They are not afraid to ask awkward questions.”

This is something Kaci Kullman Five, one-time senior executive at Aker – also a former trade minister and current member of the Norwegian Nobel committee – knows only too well. She was briefly acting head of Norway’s giant state-run oil company Statoil in 2003, after its chief executive was forced to resign in a scandal over alleged bribery in its dealings with Iran. “Women are better at working as part of a team and listen more than men, who tend to stick to positions for the sake of their pride,” says Kullman Five, who sits on five company boards.

The growing number of women who now sit on a wide variety of boards brings accusations that, just like men, senior businesswomen are now creating their own exclusive “club”.

It’s almost taboo to admit this openly, says Stig Fagerland, but what is happening in some cases is that older women are pulling up the ladder behind them and leaving younger talent behind.

“I tell young women now to ‘Watch out for the long-stockings!’ ” she laughs. “There will always be plenty of things that women need to fight for, even here in Norway, like equal wages. But I feel more like a relay runner now, ready to pass the baton on to my daughters one day.”