February 1, 2009

February 1, 2009

Investigation

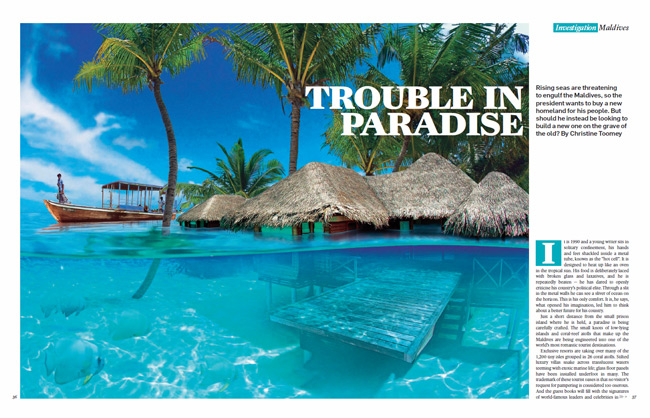

Rising seas are threatening to engulf the Maldives, so the president wants to buy a new homeland for his people. But should he instead be looking to build a new one on the grave of the old?

It is 1990 and a young writer sits in solitary confinement, his hands and feet shackled inside a metal tube, known as the “hot cell”. It is designed to heat up like an oven in the tropical sun. His food is deliberately laced with broken glass and laxatives, and he is repeatedly beaten — he has dared to openly criticise his country’s political elite. Through a slit in the metal walls he can see a sliver of ocean on the horizon. This is his only comfort. It is, he says, what opened his imagination, led him to think about a better future for his country.

Just a short distance from the small prison island where he is held, a paradise is being carefully crafted. The small knots of low-lying islands and coral-reef atolls that make up the Maldives are being engineered into one of the world’s most romantic tourist destinations.

Exclusive resorts are taking over many of the 1,200 tiny isles grouped in 26 coral atolls. Stilted luxury villas snake across translucent waters teeming with exotic marine life; glass floor panels have been installed underfoot in many. The trademark of these tourist oases is that no visitor’s request for pampering is considered too onerous. And the guest books will fill with the signatures of world-famous leaders and celebrities in the years to come. The daily grind for most Maldivians — prohibited from visiting these resorts to prevent what the government calls “cultural contamination” — was different. Little tourist revenue filtered down, and all dissent was brutally quashed. Those who criticised the country’s president, Maumoon Abdul Gayoom — who ruled his country with an iron fist from 1978, and became Asia’s longest-serving leader — were beaten and thrown in jail.

The number of inmates on prison islands like Dhoonidhoo, where the young writer was held, burgeoned. Corruption was rife, and drugs, with their related crime and violence, were allowed to flow into the country virtually unchecked.

Islanders in the more remote atolls still led the traditional life, living in single-storey homes built of coral fragments on streets made of sand with the sea never far away. Most survived from fishing and trading, taking advantage of the strategic position of their small nation, once a British protectorate, at an important shipping crossroads 400 miles off the southwest tip of Sri Lanka.

But as the population expanded, more and more people moved to the capital, Male, an island of less than a square mile, where overcrowding in low-quality apartment blocks became so acute that families were forced to sleep in shifts. Mountains of garbage accumulated in the streets and raw sewage was pumped into the sea.

In 1989, Gayoom’s government hosted the first-ever conference of small island states threatened by sea-level rises. The serious threat of global warming was only just coming onto the public radar, but Gayoom paid little attention. His priority was promoting tourist development. Now, 20 years later, Gayoom has gone, and a new menace threatens the Maldives. The battle for democracy has been won — but the battle against the force of nature is just beginning.

The young writer repeatedly tortured and imprisoned 20 years ago is strapped into the seat beside me as our plane lifts away from Male. His name is Mohamed Nasheed and he has only recently been elected president of the Maldives. Pointing out of the window at a seemingly uninhabited teardrop of green below, he shows me the prison island of Dhoonidhoo, where he was held the first of 13 times he was jailed for dissent. It is then that he begins talking about the effect his incarceration there had on his determination to “think big”.

“All you have to do when you are in prison is think, and even then I knew we were going to need dramatic solutions to the problems my country faces,” says Nasheed, a slightly built man of 41 with a high-pitched voice.

In 2004 the former dissident was granted political asylum in the UK, and it was here that he consolidated his opposition movement, finally overthrowing Gayoom in elections in October 2008. When we meet, the man his countrymen call “Anni” has had little time to introduce many changes. But one of his “big ideas” has grabbed global attention. Shortly after taking office, Nasheed made the dramatic announcement that he intends to start banking enough tourist pounds and dollars to buy a new safe homeland in which to relocate his 386,000 citizens when — not if — rising sea levels make the Maldives uninhabitable. Tracts of land in Australia, India and Sri Lanka are said to be under consideration for purchase. Nasheed’s plan caught the attention of the world’s media and led to a flurry of doomsday headlines painting a picture of a nation packing their bags and decamping en masse, waves lapping at their ankles. The truth, as always, is more complex.

According to the latest scientific estimates, sea levels are expected to rise worldwide by up to 60 centimetres by the end of this century as a result of climbing temperatures and shifting weather patterns associated with the build-up of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. And this does not even take into account how much further sea levels could rise if the ice sheets of Greenland and west Antarctica start melting at ever more rapid rates.

But is it really feasible for an entire country to relocate itself to higher land? If so, how long would it be before it became necessary, and how do its people feel about such a prospect?

Nasheed leads me to his modest office at the back of the presidential complex. He refuses to use the opulent rooms Gayoom once occupied and plans to turn the sumptuous presidential palace into his country’s first university; one reason he thinks the Maldives has so many environmental problems is that Gayoom actively discouraged academic research and scientific inquiry among his countrymen, on the grounds that too much critical thinking could threaten his hold on power.

Nasheed explains that he has just received a visitor from Dubai. The businessman from the global investment company Dubai World — the company responsible for such futuristic land-reclamation projects in the United Arab Emirates as the Palm Islands and the World — had come to discuss the possibility of building underwater resorts for well-heeled tourists in the Maldives.

The president is reluctant to discuss the details. But one thing is clear: for those with money, whatever problems climate change brings will be regarded as little more than a financial challenge to be overcome with elaborate solutions. This is not the case for the majority of Maldivians. The country’s reputation as the richest nation in South Asia is misleading: its £3,100 GDP per head is unevenly spread; 42% of the population still live close to the poverty line.

“Every evil you think a society could have has found a home here in the Maldives,” Nasheed says. “We have inherited beautiful buildings from the previous regime, but almost empty coffers. There is an acute shortage of housing, sanitation, water, health, education, transport and basic infrastructures for a decent life.”

In addition, 30% of the country’s youth (and 75% of the population is below 35 years old) are now heroin addicts. Faced with such pressing social concerns, it seems surprising that Nasheed should give any thought to the long-term problems his country faces. “We’re in the front line of rising sea levels and we have to be prepared. I don’t want my grandchildren to end up as environmental refugees,” explains the president, who has two daughters aged 6 and 11.

The Maldives faced their first serious environmental wake-up call in 1998 when shifting ocean patterns associated with El Niño caused sea temperatures to rise to such a degree that normally vibrantly coloured tropical coral reefs around the globe suffered extensive bleaching, which causes the algae they feed on to migrate or die. Nowhere was this more dramatic than in the Maldives. Between 70% and 90% of all coral reefs surrounding the country’s 26 atolls are estimated to have died as a result. One diver swimming the length of reefs in North Male atoll at the time described it as an underwater equivalent of the snowcapped Alps.

Once the reefs died, coastal erosion escalated and the islands were left more exposed to the elements of nature than ever. Their vulnerability was graphically illustrated in December 2004, when the Maldives offered the tsunami of that Christmas scant resistance — it simply swept over them. With little of the damaging backwash that caused so much destruction in other Indian Ocean countries such as Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India and Thailand, the death toll in the Maldives — where 82 died and 15,000 were displaced — was low. But the tragedy led to a deep shift in the national psyche. The event was widely interpreted by the largely Sunni Muslim population as the act of an angry God. In the wake of the disaster, the proportion of women wearing religious head coverings in the country soared.

In an effort to win political favour – Nasheed’s opposition movement was by then gaining momentum – Gayoom went ahead with a rapid programme of artificial-harbour construction. More than three dozen additional harbours were built on the country’s 200 inhabited islands in less than three years.

Just as the destruction of coral reefs had a disastrous effect on the islands’ natural defences, so too did this construction programme, which drastically altered sea currents surrounding the affected islands, leading to more coastal erosion.

As I trail Nasheed and his environment minister, Mohamed Aslam, on a visit to one of the Maldives’ southernmost atolls and then travel to islands in the north to see such damage first-hand, the prospect of the Maldives one day disappearing beneath the waves becomes a lot more believable. It is already happening to part of Maduvvaree island in the northern Raa atoll, and the fear and disbelief are written on the face of the 45-year-old fisherman Abdullah Kamal.

Two years ago there were more than 50 metres of grass and sandy beach between the sea and the home where Kamal lives with his wife and eight children. Now the beach has vanished, the result of changing sea currents caused by a harbour built on the opposite side of the island. Some of Kamal’s neighbours’ houses have already collapsed into the sea.

“At night I lie awake and listen to the water lapping against the back wall of our house. The children cry. They’re very afraid, but we have nowhere else to go,” says Kamal. He has heard about the president’s plan to start saving money to buy a new homeland if the Maldives are one day inundated. But he does not believe his countrymen would want to move so far away. “We’re a nation of fishermen, and if they try to change that, our wings would be broken.”

Just how quickly sea levels will rise as a result of global warming is uncertain. But, as Aslam says, the effect of even a moderate rise in such a low-lying country as his will be quick and drastic. “If the predictions are right, in less than 50 years we could be in a really bad situation,” he says.

With only a 10-centimetre rise in sea levels Aslam paints a scenario in which coral reefs will begin to permanently lose their breakwater function. Not only will this lead to even more rapid coastal erosion, but the freshwater reserves that islands store in subterranean water tables will become saline and vegetation will die, leading to further soil erosion.

More than 100,000 people now live in Male, making it one of the most densely populated towns on Earth. The neighbouring island of Hulhumale, or New Male, has been designated to accommodate the overflow. A massive land-reclamation project to build an artificial island with an elevation of three metres is nearing completion. This project is cited by some as the way forward for constructing “contingency islands” to which the population could be moved when climate change makes the rest of the lower-lying islands uninhabitable.

The country’s influential environmental group Bluepeace proposes that seven such safe islands be developed in different areas of the archipelago to give Maldivians the chance of continuing to live there as sea levels rise.

“Most wouldn’t choose to leave and live thousands of miles from here,” says one of the group’s founders, Ali Rilwan. “We’re a very old civilisation. We wouldn’t want to be second- or third-class citizens somewhere else.”

Neither Nasheed nor Aslam rules out the construction of such safe islands, yet the president is in no mood for discussing such compromises. “People are either blissfully unaware of what climate change will bring, or are fed up with hearing about doomsday scenarios. So we must have imagination to make positive proposals.”

That is where Nasheed’s plan to establish a sovereign fund comes in. He believes it is essential that his countrymen also eventually have a “dry-land option”, a place where they can move within a bigger landmass. “It has to be there, as an anchor, to give confidence,” he says, as if talking about buying a simple insurance policy.

Of the $45m the government currently earns annually from tourism, Nasheed plans to start putting aside at least $2m a year into a fund, with contributions increasing substantially over time. This seems unlikely to be enough to buy a sizable chunk of land in the near future in such mooted destinations as Australia. But the government’s intention, he says, is that this fund be supplemented by donations from the richer nations that bear the brunt of responsibility for global warming.

Charity organisations are also calling for rich countries, such as the UK, to do more to help the developing world adapt to the effects of climate change, storms, famines and droughts. Oxfam, for instance, has called for at least $50 billion a year to be released from international carbon-trading programmes to help poor countries introduce adaptation schemes, such as upgraded early-warning systems for flooding.

When pressed, however, Nasheed says he only mentioned Australia as a possible destination out of solidarity with other small island states in the South Pacific such as Tuvalu and Kiribati, for which the rising oceans are also a ticking time bomb. Regional think-tanks are already urging the Australian government to draw up plans to relocate the small populations of these atoll states through staged migration as land becomes increasingly uninhabitable. A more realistic destination for Maldivians, says their president, would be a tract of land in one of the southern states in India, such as Kerala, where the relocation of 386,000 in a country with a population of 1.14 billion might be more feasible. “No country has said they will not have us,” says Nasheed. “We are going into unknown territory, so we have to have the vision to believe a new future is possible. If the Maldives is going to be underwater, for instance, who owns it? And if we move to another country, are we still a sovereign nation?”

While some may dismiss Nasheed as a dreamer, the questions he poses about his tiny island state will be multiplied by the vast areas of much more populous countries such as Bangladesh, China, Vietnam and Egypt that will also be inundated by rising sea levels. In Bangladesh alone, 17% of the country’s landmass is expected to be submerged in the next 40 years, making at least 20m homeless.

The spacious concrete-block houses lined up in the sand on the island of Dhuvaafaru in the northern Raa atoll have a very different feel from the traditional cramped dwellings of coral fragments on other remote islands in the Maldives. Little wonder, since these houses have only just been built by the International Red Cross and the Red Crescent to rehouse the entire population of the nearby island of Kandholhudhoo, whose houses were destroyed by the 2004 tsunami.

It is only two weeks since the 4,000 islanders moved into their new homes. For the past four years, most have been living in sweltering tents in scattered refugee camps on other islands. Here, at least, you might imagine that the population would be aware of the dangers future generations face from climate change. But there is little sign of it. “I do not believe that the climate will change and the sea will rise,” says Fauziyya Mahir, a 43-year-old mother of seven, as her fisherman husband sits in silence close by. “No matter what happens, I believe God will take care of us. I don’t think our new president should be talking about such things. We have enough other problems that need solving, like crime and drug addiction.”

Her view is typical, explains Dr Ahmed Razi, one of the community’s leaders. “It has taken scientists decades to accept that climate change is happening, so it is quite understandable that lay people don’t believe it. Fishermen are fatalistic by nature, and as a nation we are a religious people, so many people’s attitude will be to leave whatever will happen to fate.”

But fishermen in the capital, Male, say that they have already noticed significant changes in the local weather patterns. For more than 1,000 years a traditional calendar of sea-and-wind patterns known as the nakaiy existed in the Maldives, its frequent changes so reliable that its patterns were passed from father to son.

Ahmed Waheed shakes his head when talking of the nakaiy now. Resting in the shade of the cabin of his boat with his crew, the 53-year-old says the traditional period of calmer weather between December and April is now much more changeable, with higher winds and rougher seas. “But why should we be afraid of the sea level rising when our life is the sea?” he says, to which the rest of his crew nods.

“One of the biggest problems we face is a lack of understanding of how our islands are changing,” concedes Aslam, the country’s environment minister, who was recently held hostage for several hours by islanders in the south demanding he set a date for providing their community with a new harbour. He refused to bow to such pressure and eventually had to be set free by police.

As we sit talking, Aslam laughs off the incident, but sympathises with the frustration of his countrymen. “We welcome the international scientific community to come to the Maldives and use us as a laboratory for understanding the dynamics of our islands and the global implications of climate change,” he concludes.

When Nasheed joins us for supper, I am reminded of something that the young president said earlier: “The Maldives is the canary in the world’s carbon coal mine.”