6th August, 2011

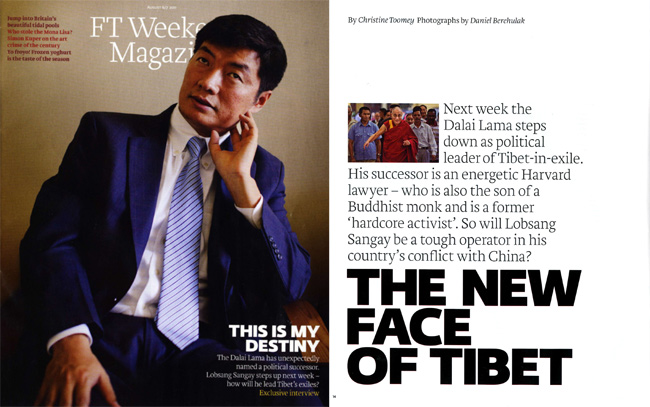

Next week the Dalai Lama steps down as political leader of Tibet-in-exile. His successor is an energetic Harvard lawyer who is also the son of a Buddhist monk and is a former “hardcore activist”. So will Lobsang Sangay be a tough operator in his country’s conflict with China? By Christine Toomey.

Lobsang Sangay doesn’t know the exact day on which he was born. Nor did most of the small boys and girls who turned up with him for their first day of school, clutching the hands of parents too traumatised to truly mark such things as birthdays. But were it not for the bloodshed his father had witnessed, Sangay would not have been born at all. For more than twenty years before his son’s birth in 1968 his father had been a Buddhist monk in a remote monastery in Tibet.

When it came to entering Sangay’s details in the school register his parents nominated the day of his birth as March 10th. So did the parents of a third of his classmates. To Tibetans March 10th is known as National Uprising Day, marking the height of the 1959 armed rebellion against Chinese domination of their ancient homeland.

“The story of my life as a refugee is all there in not even knowing my own birthday,” Sangay reflects with the air of a man well acquainted with hardship.

Out of the window of the small plane in which we are flying towards the North Indian hill station of Dharamshala, the snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas loom into view. None of the other passengers on the plane give Sangay a second glance. But while he may still be a complete unknown, in a matter of days he will step into the shoes of one of the most instantly recognisable figures on the planet.

On August 8th this towering, talkative and engaging 43-year-old will take over the temporal duties of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, who stunned his devotees last March when he announced that he would be retiring this summer from his role as political leader of the exiled Tibetan movement he has spearheaded for the past five decades.

The story of how this has come about unfolds as our plane follows the line of the Himalayas north. Sangay talks in painful detail of the events that forced his parents to trek across these mountains when resistance to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army proved futile. For years before this the PLA had been brutalising Tibet, especially targeting monasteries and nunneries in an attempt to break the people’s deep Buddhist faith and bring the strategically critical territory within the communist fold.

As a boy Sangay recalls his father talking of a river close to his monastery in eastern Tibet running red with the blood of slaughtered monks. It was in the face of such savagery that his father abandoned monastic orders and briefly became a resistance fighter before joining the tens of thousands of Tibetans who fled across the Himalayas into Nepal, following their spiritual leader the Dalai Lama into exile.

Thousands of exiled Tibetans endured backbreaking work as hard labourers or scraped a living from small plots of land surrounding makeshift refugee camps. Children were born in haphazard conditions. Sangay and his two younger siblings were raised close to one of these camps in Darjeeling, West Bengal, where his father had met and married his mother after she was abandoned as a teenager because she had broken a leg while fleeing across the Himalayas.

Despite such harsh origins Sangay fought his way out poverty through academic graft. When he excelled at school his parents sold one of the family’s three cows to pay for his education. After a stint at university in Delhi, he won a scholarship to Harvard Law School, remaining there as a senior research fellow, living a privileged western lifestyle, for the past fifteen years. Then his life took an extraordinary turn when the Dalai Lama made his surprise announcement on March 10th – Sangay’s 43rd “birthday”.

Sangay was in Dharamshala at the time. For months he had been campaigning for a post called the Kalon Tripa, or Prime Minister, of the Tibetan government-in-exile, a role that has traditionally been little more than an administrative post within an organisation largely subordinate to the Dalai Lama himself. Sangay had been encouraged to put himself forward by those who wanted to see a younger layperson in the role that had previously been held only by senior Buddhist priests.

In recent years Tibet has been rocked by demonstrations against the discrimination suffered by the six million Tibetans who now find themselves living within China. Two thirds of them live far beyond the borders of what the Chinese euphemistically call the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) which covers only half of what Tibetans claim as their ancient territory.

Since the violent crackdown on protestors on the streets of Llasa in 2008, human rights groups report there are now more Tibetan political prisoners in Chinese jails than at any time in recent history. According to GuChuSum, an organisation which helps former political prisoners who have escaped from Tibet, there were at least 824 named political prisoners in detention in March 2011. The whereabouts of many more is unknown.

In the face of such unrest and tensions amongst those in the 145,000 strong exile community around the world, Sangay was seen as a much-needed, dynamic, and highly qualified shot in the arm for the exile leadership. At Harvard he specialised in international human rights law and much of his energy has been devoted to bringing Tibetan and Chinese academics together.

Yet little had prepared Sangay for the Dalai Lama’s retirement announcement. For the past three hundred years, successive Dalai Lamas have fulfilled the dual role of supreme spiritual guide and political figurehead. But as the current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, has slipped further into old age, the 76-year-old has made it increasingly clear he wants to end the “culture of dependency” that has grown around him.

“As early as the 1960s, I have repeatedly stressed that Tibetans need a leader, elected freely by the Tibetan people, to whom I can devolve power. Now we have clearly reached the time to put this into effect,” he announced on March 10th. In future, he declared, political leadership will rest with whoever is elected Kalon Tripa.

When Sangay heard these words he sank into “denial mode”. “That day was the start of a real emotional roller coaster, many anxious moments and a lot of introspection,” he says. “I realised, if what His Holiness was saying went through it could be me stepping into his shoes.” Several weeks later his anxiety proved well founded. On April 26th the results of a poll conducted over several months within the exile community elected Sangay as the next Kalon Tripa.

When I ask Sangay how he now feels about taking over the temporal duties of a man regarded by his followers as a living god at a time when Tibet stands at such a critical crossroads Sangay replies that it is his “leh”, or karmic destiny.

Despite this self-effacing manner, those who know Sangay describe him as “extremely ambitious”, an unusual trait in Tibetan culture, which values humility as one of the highest virtues. Married to a descendent of one of the founding kings of Tibet, he and his wife, also born in exile, have a three-year-old daughter. He plans to move his family to Dharamsala once he takes up his new position.

Sangay tells a touching story of how hard it had been, given his impoverished background, to win the approval of his wife’s parents for her hand in marriage. “I told my wife’s father “I am nothing now and maybe I don’t deserve your daughter. But one day I’ll show you I will be someone.” Fortunately he took me at my word,” he says, a broad smile spreading across his handsome features.

As our plane touches down Sangay slips on a pair of aviator sunglasses and emerges onto the tarmac swinging his finely cut suit jacket over his towering, athletic frame – he has become an avid American baseball fan. A starker contrast to the balding, be-robed holy man whose political role he is about to assume would be harder to imagine.

While to the Chinese authorities who rule Tibet with an iron fist the Dalai Lama is “a wolf wrapped in robes, a monster with a human face and an animal’s heart”, to millions of Buddhists around the world he is the 14th reincarnation of the supreme Buddha of Compassion. Globally he is regarded as an icon for peace; in 1989 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his consistent opposition to violence in his quest for Tibetan self-rule. These are large shoes to fill.

Despite Sangay’s insistence that he will continue to support the Dalai Lama’s long-held stance for peaceful negotiations – the so-called “Middle Way” – some point to his praise for the “Jasmine Revolution” in the Arab world as an indication this could change in future. “The new leader (of Tibet) will have to take advantage of the changes in the Muslim world. When the opportunity presents itself, one must take advantage,” he said while campaigning, leading some to speculate whether Tibet could also face its equivalent of the “Arab Spring”.

Until now the moral weight the Dalai Lama has carried has kept a lid on the situation becoming more volatile. One sign of the concern many feel at the prospect of this restraining influence diminishing are the pleas, culminating in a formal petition by the government-in-exile, that he change his mind about ceding his temporal power. When the Dalai Lama refused, he was asked to consider continuing as a “ceremonial head of state” with a constitutional role similar to that of the British monarchy. “If you give me a queen, maybe I will reconsider,” the aging monk quipped before firmly declining the request.

While his supporters laud the Dalai Lama’s decision to democratise his people’s leadership, at a time when autocrats around the world are brutally clinging onto power, a few outspoken critics believe now is not the time for him to go. “I see nothing wonderful in a shepherd abandoning his flock mid-way through the desert,” says Llasang Tsering, a former president of the Tibetan Youth Congress, who refers to himself as “the resident devil” of Dharamshala because he dares voice a different view from the Dalai Lama’s.

Tsering believes it is time for Tibetans to admit that the Middle Way has not worked and change to more confrontational tactics. “China has no need to negotiate with a bunch of poor refugees,” he argues. “People are dying for true freedom in Tibet and they need international support. They need it now before it is too late. Tibet is not just about the fate of 6 million people it is about control of the roof of the world, an area two-thirds the size of Europe with vast mineral reserves, where all the major rivers of Asia have their source and where China has untold numbers of strategic missile bases.” From the point of view of Beijing, which has just celebrated its 60th anniversary of “the peaceful liberation of Tibet”, China brought “democracy” to a benighted and backward nation of serfs, while today providing the region with modernity and development through huge amounts of investment.

But given China’s economic clout and the fact that Beijing threatens ill-defined consequences for any country that agrees to formal contact with the Dalai Lama, a sudden wave of official support for Tibet by the international community seems a forlorn hope. Despite being feted as a man of peace, not least by adoring Hollywood stars, most of the Dalai Lama’s contact with foreign leaders is in an informal capacity as a religious figurehead. This spiritual back door will not be open to Sangay.

In addition to battling international indifference Sangay will also have to contend with increasing tensions between older and younger Tibetans. Growing numbers of the younger generation – increasingly frustrated, tech-savvy and radical – now support full independence. “Tibetan youngsters are increasingly educated and aware of their rights. They are fed up of Tibetans being depicted as some kind of exotic tribe,” says Tenzin Tsundue, a Tibetan writer and freedom activist.

Within Tibet the young are resorting to desperate measures. On March 16th a 20-year-old monk at Kirti monastery in the far north set himself alight, later dying of his injuries, in protest at growing Chinese repression. This led to 300 monks from this one institution alone being arrested and taken to an unknown location. “According to our Buddhist faith we should cause neither others nor ourselves harm, so suicide is considered gravely wrong. But the situation in Tibet is now so critical people are feeling desperate,” says Kanyag Tsering a senior monk at an affiliated monastery in Dharamshala.

The treatment those arrested can expect is graphically illustrated by one former nun who escaped from Tibet via Nepal in 2004. She is still so traumatised she requests to meet on a remote hillside in Dharamshala where no-one can overhear us. After being arrested when she was 16, Nyima, now 32, describes how she was tortured in prison for five years. In summer she was forced to stand all day outside on a box with sheets of newspaper stuck under her armpits and between her legs – if the newspapers slipped she was savagely beaten. In winter she had to stand barefoot on blocks of ice until her skin peeled away from the bone. When she substituted the words of a song in praise of Chairman Mao for her own version paying tribute to the Dalai Lama she was locked in solitary confinement for twenty one months. “I want people to know what is happening inside Tibet. If people know this how can they not help,” she says in a voice barely louder than a whisper. “It’s true we need urgent help. Time is running out. Very soon Tibet will be nothing more than a giant museum, our culture will effectively be dead,” concludes Kanyag Tsering.

Despite such desperation Sangay insists he will stick to pacifist principles in tackling the leadership challenge he now faces. “Look what Gandhi achieved with his non-violent movement! I do believe eventually Tibet can succeed too. If it does, this will be the most beautiful story of the twenty first century,” he says throwing his arms in the air as if in supplication. Shifting geo-politics, he argues, will eventually lead to a break-through in the impasse in Chinese-Tibetan relations.

It is a cautious and conciliatory argument. But Sangay gives the impression of a man who plays his cards close to his chest. He is clearly a shrewd operator. In a culture that frowns on self-promotion he delights in describing how he campaigned for the post of Kalon Tripa by “not campaigning”, instead touring refugee communities throughout India giving lectures so that his face was more instantly recognisable than his rivals at the polls.

In his youth Sangay admits he was a “hard-core activist”, his early student days frequently interrupted by short spells in jail for protesting in favour of Tibetan independence. He claims he has mellowed with age, quoting Churchill’s adage that if you’re not liberal when you are young you have no heart and if you’re are not conservative by 40 you have no head.

The only flicker of what Sangay really feels about the Chinese regime comes in an anecdote about how he requested permission to travel to Llasa several years ago – like most exiles below the age of 50 he has never set foot inside Tibet. Following the death of his father, he wanted to travel to the Tibetan capital to light a traditional butter lamp in his memory. He was refused. “That was very painful,” says Sangay. “I realised then what sort of people I was dealing with.”

Sangay does go on to admit, however, that if the stalemate in negotiations with the Chinese continues “and the people want me to change policy I will.” “That doesn’t mean I’m advocating official policy should change. But wherever there is repression there is resistance,” he concludes, drawing on another well-worn quote – this time from Tibet’s former nemesis Mao Zedong.

Given this possibility that the Dalai Lama’s political successor could adopt a much tougher position in future the question of who will one day take over as Tibet’s spiritual leader becomes ever more pressing. Few doubt Beijing will attempt to install its own handpicked spiritual successor. Flying in the face of centuries of tradition, during which successive Dalai Lamas have been recognised through a mysterious process of prayer and divination, the officially atheist Chinese government saw no irony in announcing in 2007 that it alone has the right to determine who will succeed Tenzin Gyatso.

Meanwhile the Dalai Lama himself is said to be considering alternative scenarios for his spiritual succession. According to his nephew and official spokesman, Tenzin Takhla, his uncle will be convening the latest of several meetings of senior lamas to discuss this in Dharamshala in September. “Right now there is no urgency and most Tibetans don’t even want to think about it. The important thing now is to let everything surrounding the change in political leadership settle down,” says Takhla, seated in a sunlit antechamber of the Dalai Lama’s private residence. “But this is something that His Holiness has been thinking about for some time.”

* * * * *

Twenty kilometres along a deeply rutted road from Dharamshala, one possible successor to the Dalai Lama sits under virtual house arrest. Ever since his dramatic escape from Tibet in January 2000 at the age of fourteen, after days of treacherous driving through mountain passes, trekking around checkpoints and a spell on horseback, Ogyen Trinley Dorje has been treated with deep suspicion by the Indian authorities. Security agents are permanently posted outside his private quarters at the Gyuto monastery in Sidhbara.

As head of the Karma Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, Dorje is one of two claimants to the title of the 17th Karmapa, a reincarnation of Buddha pre-dating that of the Dalai Lama by more than two hundred years. After the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama – the second highest-ranking lama of the Gelug order – the Karmapa is widely regarded as third in line in the Tibetan spiritual hierarchy, in as much as such an esoteric order exists.

The position of Karmapa took on greater significance, however, after the mysterious disappearance in Tibet of five-year-old Gendun Choekyi Nyima, identified by the Dalai Lama through traditional divination as the 11th Panchen Lama in 1995. Shortly after his selection the boy was detained by the Chinese authorities and has not been seen since; despite Chinese claims that he is now living quietly with his family somewhere in Tibet. The five-year-old son of two Communist Party members subsequently appointed by the Chinese as their choice for Panchen Lama is rejected by devout Tibetans.

Following Dorje’s escape from Tibet, the Indian authorities threw doubt on whether China would have allowed such a senior religious figure to flee. Rumours started circulating that he was a Chinese spy. Indian courts have since recognised a Tibetan exile two years older than Dorje as the legal heir to the role of Karmapa, although the Dalai Lama recognises Dorje as the true holder of the title.

Dorje’s position was further complicated earlier this year when more than $1million in foreign currencies, much of it in Chinese yuan, was found stashed in trunks at Gyuto monastery. Sensational headlines in the Indian press questioning whether he was a Chinese “mole” brought calls from the Dalai Lama and others in the exile community for the money to be properly accounted for.

According to the Karmapa’s entourage the money came from unsolicited donations from devotees trying to help him build a new monastery. The money had not been deposited in bank accounts, they explained, because of the bureaucratic nightmare Tibetans face conducting any transactions in a country where, as refugees, they have little legal status. Even though this explanation was widely accepted, Dorje is still treated with suspicion by the Indian administration, which closely controls public access to him.

Against this background I expect the Karmapa to be extremely guarded. On the contrary he seems relieved to have the opportunity to address the allegations. On a brief visit to the United States in 2008, Dorje, 25, was introduced at one event as “His Hotness” because of his youthful good looks. Much has been made of his reported penchant for video games and X-Men comics.

But on the morning we meet he appears serious and studious in his monk’s robes and rimless glasses, the only nod to worldliness immaculately manicured nails. Seated in a small airy room at the apex of Gyuto monastery, an interpreter at his feet, Dorje is quick to answer the allegation that he is a Chinese spy, describing it as “hurtful to the core”.

“I am a full blooded Tibetan and for any Tibetan to be accused of being a Chinese spy there can be nothing worse. As a practitioner of Buddhist Dharma I have trained not to harm others. So to say that I came here to harm India and threaten national security, nothing can make a deeper wound,” he says. “When I escaped Tibet I was prepared that I could be killed at any moment so I was prepared for feelings of concern and fear and doubt. But I was not prepared for what I have had to face here. For anyone this would be difficult to forget.”

When I ask the Karmapa what he thinks of one of the possibilities suggested to me by Tenzin Takhla, that he could one day become the next Dalai Lama, Dorje dismisses it saying “No-one can be the Dalai Lama except the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation. He is the one and only.” He has heard nothing, he says, of the imminent discussions to consider the Dalai Lama’s eventual spiritual succession. In the past the Dalai Lama has also raised the prospect that the role could die with him if the Tibetan people felt they had no use for another Dalai Lama after his death. He has also spoken of the possibility of a female successor, adding that if this were to happen he hoped the woman would be beautiful.

Following the Chinese government’s decree that only it can decide who will succeed the Dalai Lama, however, the prospect of a “duel of the Dalai Lamas” in future looms. Dorje says he is confident the Dalai Lama will make a very clear statement about his spiritual succession when the time is right “so there will be no opportunity for manipulation.” Sangay too is adamant that if the Chinese authorities appoint their own Dalai Lama they will fail “just as they are failing with their Panchen Lama,” who he describes as “a parrot in a golden cage in Beijing.”

For a culture based on Buddhist principles of tolerance, compassion and non-violence, however, all this uncertainty over the future direction of both spiritual and political leadership augurs gathering storm clouds over Tibet. For all the Dalai Lama’s messages of peace in evidence there is now a more forceful mantra pinned up everywhere in Dharamshala. “No matter what is happening. No matter what is going on around you,” it reads. “Never give up! Never give up!”

Photographs by Daniel Berehulak