July 07, 2002

July 07, 2002

INVESTIGATION

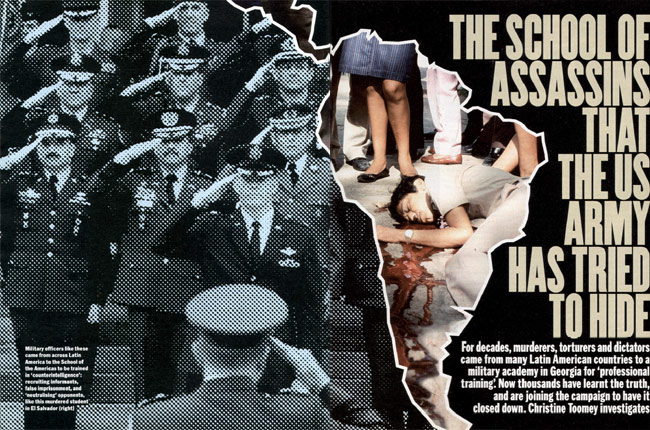

For decades, murderers, torturers and dictators came from many Latin American countries to a military academy in Georgia for ‘professional training’. Now thousands have learnt the truth, and are joining the campaign to have it closed down. Christine Toomey investigates

As Major Joseph Blair – United States Army, retired – tells it, the incident was ‘funny as hell’. There was Colonel Pablo Belmar, one of Augusto Pinochet’s most notorious henchmen – accused of torture and murder during Chile’s military dictatorship – his chest puffed out, in full-dress uniform, delivering a four-hour lecture on human rights. Snickering and joking among themselves at the back of the class were senior military officers from Guatemala and El Salvador. ‘Guys,’ says Blair, ‘who had just participated in the genocides of Central America. No one asked any questions. They just sat listening to Belmar go, ‘Here’s the Geneva Convention. Here’s the Hague Convention. It’s on the slide. Read it. Now let’s get onto the next thing.’ No one was interested.’ Blair gulps back laughter as he recalls their reaction: ‘They were going, ‘Oh, bullsh. Human rights exist at the point of a gun.’’

An edge of hysteria and despair has crept into Blair’s voice. He is exhausted. He has spent six hours cataloguing a series of abuses that took place at a military training facility known by opponents as the School of Assassins. It sounds as if the scene described might have happened in some obscure corner of a Latin American country where few dare to challenge a man in uniform. It did not. It took place in 1987 at the heart of America’s military establishment. The class was held at an academy called the School of the Americas (SOA), located at Fort Benning, the infantry HQ of the United States Army, in rolling hills on the outskirts of Columbus, Georgia.

Late into the evening, with the summer heat of the Deep South becoming oppressive, Blair pulls file after file out of a large cardboard box as he delves deep into an ugly chapter of his country’s military past that the Pentagon has, in recent months, taken measures to erase. Blair knows what he is talking about. He was once a senior logistics instructor at the Spanish-language training facility, set up more than 50 years ago (and run at taxpayers’ expense) with the stated aim of providing ‘professional training’ for soldiers from Latin America and ‘inculcating them with American notions of democracy’.

Leafing through a report, across which he has scrawled ‘torture manuals’, Blair talks of how soldiers were given counterintelligence instruction, which included the best methods of recruiting and controlling informants (arresting and beating their relatives, if necessary), extortion, blackmail, false imprisonment, how to administer a truth serum intravenously, and how opponents could best be ‘neutralised’ – a euphemism for executed.

Not only did the American military turn a blind eye to known human-rights abusers attending and lecturing at the academy, says Blair, it also paid their membership to exclusive golf clubs during the time they spent there, plied them with tickets to big sporting events and took them on outings to Disneyland. He goes on to describe how soldiers routinely arrived at the academy with suitcases stuffed with tens of thousands of dollar bills, which they used to buy new cars and luxury household goods to be shipped back to their own countries.

‘It was common knowledge that the School of the Americas was the best place a Latin American officer could go to launder his drug money,’ says Blair, who retired from the army in 1989, with his conscience about what he had witnessed at the academy increasingly troubling him.

A few months after he retired, six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her teenage daughter were murdered by the military in El Salvador. When an investigating team of US congressmen identified 19 of the 26 Salvadorian soldiers held responsible for the deaths as graduates of the School of the Americas, Blair, a devout Catholic, felt he could remain silent no longer. One of the senior officers responsible for planning the murders was Colonel Francisco Elena Fuentes, head of a Salvadorian death squad called the Patriotic Ones. Elena Fuentes had been a senior guest instructor at the SOA in 1986, and for much of that time had occupied the desk next to Blair. ‘He was treated as a top dog there,’ says the retired major. ‘They kept inviting him back, year after year.’

It was enough to push Blair to join a growing band of protesters campaigning to have the School of the Americas closed down. After the school’s association with those involved in the Jesuits’ murder was revealed, the protesters demanded that details of all those who had attended the school be declassified. This brought to light a roll call of senior alumni which read like a who’s who of the most brutal military dictators and human-rights violators in Latin America over the past five decades: Manuel Noriega and Omar Torrijos of Panama; Anastasio Somoza of Nicaragua; Leopoldo Galtieri of Argentina; Generals Hector Gramajo and Manuel Antonio Callejas of Guatemala; Hugo Banzar Suarez of Bolivia; the El Salvador death-squad leader Roberto D’Aubuisson. A more detailed examination of the declassified lists reveals that more than 500 soldiers who had received training at the academy have since been held responsible for some of the most hideous atrocities carried out in countries in the region during the years they were racked by civil wars and since.

The American military claims there is no link between the academy and the appalling record of some of its alumni. They dismiss these brutal graduates as ‘a few bad apples’. Some, they say, only attended brief courses that would not have been enough to turn ‘bunny rabbits into rattlesnakes’. Compared with more than 60,000 soldiers who have passed through the gates of the School of the Americas since it first opened its doors at Fort Gulick in the Panama Canal Zone in 1946 – it transferred to Fort Benning in 1984 – the several hundred charged with murder, rape and genocide, they argue, are ‘statistically insignificant’.

Late last year, the School of the Americas was closed. A month later, another military training academy was inaugurated in the same building under a different name. It has many of the same staff members as its predecessor, much of the same curriculum and the same remit of training, exclusively in Spanish, soldiers and others in the security forces of countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. This crude attempt to sweep the school’s sordid legacy under the carpet has inflamed its opponents even further. They draw little distinction between the two institutions. ‘New name, same shame,’ they say, vowing to continue their campaign to have the academy closed down. As the activities of foreign military personnel trained or funded at one time by the United States come under intense scrutiny in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks – Osama bin Laden is the latest in a long line of fanatics once courted and payrolled by America – such confident disclaimers about rabbits not turning into rattlesnakes seem more questionable. The US trains more foreign military and security personnel than any other country.

Organisations such as Amnesty International have long campaigned for programmes of this kind to have sufficient respect for human rights built into them, and to be subject to far greater oversight and accountability. The civil wars of Central and South America, in which the US military and CIA were heavily involved, and which cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians, are a world away from the present conflict. But failure to act with honour and integrity, denial of culpability and refusal to apologise or attempt to rectify past injustices eventually come back to haunt any country, especially its military. Some refuse to allow such injustices to be forgotten. This is their story.

A signpost at the entrance to Fort Benning boasts that the military base is ‘The Best Army Installation in the World’. Another says all visitors are welcome. All, that is, bar a charismatic Catholic priest, Father Roy Bourgeois, and over 1,000 of his supporters. They have been issued with ‘ban-and-bar’ court orders that subject them to immediate arrest and prosecution if they cross a white line painted on the tarmac road at the entrance to the military base.

As an act of defiance, Bourgeois has installed himself in a small apartment once used as soldiers’ quarters just a few yards in front of the white line. He has been there for over 10 years. Every few years, he has crossed the line to stage a demonstration against the School of the Americas, located at the centre of the base. He has been arrested four times and has spent more than four years in prison as a result – months of it in solitary confinement.

Bourgeois was first arrested when he staged a protest after reading a 1983 newspaper item that hundreds of soldiers from El Salvador were being brought to the US for training at the academy. The priest, who had joined the Maryknoll missionary order after serving as an officer in Vietnam, had spent much of the previous decade working with the poor in Bolivia and El Salvador (then in the grip of one of the bloody cold-war conflicts consuming Latin America, in which US-backed right-wing militaries battled left-wing insurgencies).

Bourgeois had witnessed the brutality of Latin American militaries first-hand, and had been deeply shocked by the rape and murder of four Ursuline nuns, two of them his friends, at the hands of the military in El Salvador in 1980. The same year, soldiers gunned down San Salvador’s Archbishop Oscar Romero as he was saying Mass. Bourgeois did not know it then, but those responsible for both crimes had undergone training at the School of the Americas.

Late one night, Bourgeois and two supporters drove onto the military base dressed in second-hand army uniforms. They climbed a tree next to the dormitory where the Salvadorian soldiers were sleeping, and strung up a loudspeaker to blast a tape recording of the last sermon Romero had delivered before he was shot. As the soldiers came running out of their barracks, army sirens were switched on to drown out the archbishop’s words. Bourgeois and the others were dragged down, beaten, arrested and charged with trespassing and impersonating army officers, and sent to jail for 18 months.

After he was released, Bourgeois sought solace in a Trappist monastery before he started to preach to congregations around the US about the devastation being wrought in El Salvador by the military, at that time receiving more than $50m a year in funding from the US government. The murder of six Jesuit priests by the Salvadorian military in 1989 again prompted Bourgeois to take direct action. When the congressional investigation named those responsible as graduates of the academy, Bourgeois drove for 24 hours to the gates of Fort Benning, where he and a small group of supporters started a hunger strike. After soldiers threw tear gas at them and jeered as they drove past, the priest vowed to take up a permanent presence at the gates to the base until the School of the Americas was closed.

On the first anniversary of the murder of the Jesuits, Bourgeois and his supporters were arrested again after they made their way onto the base to splatter phials of blood across the facade of the academy. Again, they were sent to jail. Every year since, Bourgeois and a growing band of supporters have staged a demonstration at the gates of Fort Benning around the anniversary of the Jesuits’ deaths.

This weekend, thousands of protesters will again stage a demonstration by mounting a mock funeral procession in which coffins marked with the names of men, women and children killed by military officers trained at the School of the Americas will be paraded through the streets of Columbus.

Bourgeois admits that a driving force behind his protest movement is what he and his supporters see as the United States’ exploitative foreign policy. ‘We’re constantly being told by our president that we are a benevolent force in the world, some kind of Mother Teresa,’ says the 62-year-old, as he sits beneath a pencil drawing of the four nuns raped and murdered in El Salvador. ‘But we need to understand why so many people in the world hate us – and what went on in the School of the Americas is just one example of why some people do. Our military pays lip service to moving into the future. But this place is a cold-war relic, a dinosaur. There are some institutions that are connected to so much death, suffering and horror that they cannot be transformed, and this is one of them.’

What started as a small band of demonstrators has grown into a well-organised protest movement. Partly funded by Bourgeois’ Maryknoll order, the movement has a lobbying office in Washington, DC, and has gradually enlisted the support of both Republican and Democrat congressmen. One of its most vocal supporters during the last years he served as representative for Massachusetts was Joseph Kennedy, who condemned the School of the Americas for ‘running more dictators than any other school in the history of the world’. In recent years,the actors Susan Sarandon and Martin Sheen have added Hollywood glitz to the protest movement. Sheen has twice travelled to Columbus to link hands with demonstrators at the gates of Fort Benning. Last year he was arrested for trespassing. But most of those who gather at the gates are ordinary Americans – families with young children, college students and other nuns and priests who are prepared to go to jail in their struggle to have the military academy closed.

Earlier this year, an 88-year-old nun, Dorothy Hennessey, and her 68-year-old sister, Gwen, were among 26 men and women sentenced to six months in prison for protesting on federal property. ‘To have done nothing would have made us accomplices to what was going on at the School of the Americas,’ Sister Dorothy said in a whispery voice as she sat in an ill-fitting prison uniform in the visitors’ room of Pekin federal correctional facility, Illinois.

‘What message does it send to the world that we lock up elderly nuns while we fete torturers and assassins?’ asks Major Joseph Blair. ‘We should be bringing known human-rights abusers who have attended the School of the Americas before a war crimes tribunal and prosecuting them, just as we have the Bosnian war criminals.’

It was a tip-off about ‘inappropriate material’ contained in counterintelligence training manuals used at the School of the Americas that was to give the greatest impetus to those lobbying to have the academy closed down.

While Blair had already started talking about abuses he had witnessed during his time at the school, he was prohibited by secrecy laws from a divulging much of what he knew. But in 1996, a government report, referring to an earlier investigation by the Pentagon into CIA operations in Central America, made a brief reference to ‘improper instruction material’ used to train Latin American officers from 1982 to 1991. Congressman Kennedy made an immediate application, under the Freedom of Information Act, for the training material to be made public.

After what he described as a ‘hellish struggle’, seven manuals, written in Spanish, were eventually released. These became known as the ‘torture manuals’ and caused a public outcry. One manual, entitled Manejo de Fuente – Handling of Sources – talks of ‘the arrest or detention of the employee’s [counterintelligence agent’s] parents’ and ‘beating as part of the placement plan of said employee in the guerrilla organisation’. It goes on to talk of ‘destroying resistance’ by the external control of heat, air and light. ‘If a subject refuses to comply once a threat has been made, it must be carried out,’ the manual continues. ‘If it is not carried out, then subsequent threats will prove ineffective.’

At first, the American military said such ‘objectionable material’ contained in the manuals was never taught at the School of the Americas; it was, they said, simply provided as ‘supplementary reading material’. Then they said the manuals were supplied to only a ‘handful’ of soldiers at the school between 1989 and 1991. The government report, however, states that the manuals had already been widely distributed for use throughout Latin America by mobile teams of American intelligence advisers. Although, it concluded, the material contained in the manuals was ‘not consistent with United States policy’ and had somehow ‘evaded the established system of doctrinal controls’.

With the documents in the public domain, Blair struck out. ‘It’s bullsh to say those manuals were a violation of US policy. They were teaching this stuff for 35 years at the school,’ he told those who cared to listen. ‘Those ideas were the meat and potatoes of what you needed to get intelligence out of people.’

Although Blair himself had never taught counterintelligence at the School of the Americas, he had experience of intelligence matters in Vietnam, where he had served as an assistant to William Colby, who went on to become director of the CIA. Much of what was contained in the ‘torture manuals’, it has since emerged, was taken directly from training material used for American counterintelligence instruction in Vietnam. Over the years, a number of graduates of the School of the Americas, and soldiers who have served under officers trained at the academy, have made claims about being shown films shot by American soldiers in Vietnam. Most have spoken on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal. One Guatemalan soldier, whose commanding officers were trained at the academy, describes how he and other young conscripts were shown old black-and-white films of Vietcong being tortured during interrogation sessions by the US military. A senior military officer from Honduras, who was a student at the School of the Americas when it was located in Panama, says he was shown films demonstrating torture methods such as attaching a bucket full of stones to a man’s testicles. Others have spoken of homeless people being picked off the streets of Panama and used as guinea pigs by students learning which were the most sensitive nerve endings in the body and how individuals could be kept alive while being tortured.

Further powerful indictments of the academy come from the testimonies of those, such as Adriana Portillo-Bartow, who suffered at the hands of its students. Adriana’s 10-year-old daughter Rosaura, nine-year-old daughter Glenda, baby sister, father, stepmother and sister-in-law were all abducted by the Guatemalan military in 1981, during the country’s protracted civil war.

Adriana, who now lives in Chicago with her two remaining daughters, has never discovered the truth. But she has become the first private citizen to file a lawsuit against the Guatemalan military since a fragile peace accord was signed in her homeland five years ago. One of those she names in her suit is General Manuel Callejas, the senior intelligence officer charged with choosing targets for assassination at the time her family was abducted. Callejas is one of 38 senior military officers accused by a United Nations Truth Commission of committing atrocities who underwent training at the School of the Americas. Adriana has set up an organisation called Where Are the Children (Watch), to try to trace what happened to children such as her daughters and baby sister. After talking for a long time, her voice breaks: ‘It is my worst nightmare that I would not recognise my own children now, even if I were to pass them in the street.’

The disappearance of Adriana’s family was one of the cases outlined in a 1998 report, sponsored by Guatemala’s Catholic Church, which concluded that the military was responsible for 80% of the 150,000 deaths and 50,000 disappearances that occurred during Guatemala’s civil war. The report was intended to lay the groundwork for future prosecutions of the military. Shortly after completion, its author, Bishop Juan Gerardi, was shot dead. The military officer convicted of killing him is a graduate of School of the Americas.

As the litany of crimes committed by academy alumni has mounted, it has become the focus of intense controversy and congressional debate. Long infamous in Latin America, the training facility has become a growing embarrassment for the Pentagon too. Congress has twice voted on stopping its funding. Both times the motion has been defeated, most recently by a very small margin.

The concrete barricades that once encircled building 35 at Fort Benning have been removed. The spacious, pink Palladian mansion that housed the School of the Americas now has a welcome mat that reads Libertad, Paz y Fraternidad – Liberty, Peace and Fraternity. ‘We welcome everybody here,’ says Colonel Richard Downie, the ebullient new director of the renamed Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation.

In response to questions about how the new institute differs from its predecessor, Downie has a set response: ‘I am not all that familiar with the School of the Americas. I am the director of the Western Hemisphere Institute.’

Thumbing enthusiastically through a flip chart that details the institute’s mission, Downie is keen to stress that the institute is ‘focused on 21st-century challenges and threats – quite different from the cold-war communism and guerrilla movement challenges the School of the Americas faced. We concentrate on instruction in peacekeeping, disaster relief, border observation and counter-drug operations’, he says.

The colonel points out that the training facility, which now comes under the direct authority of the Defense Department (rather than the army) for reasons of civilian oversight, has also started teaching civilians, including police officers. Downie admits, however, that it is impossible to transform the academy overnight: ‘You have to realise that the School of the Americas closed on December 15 and we opened up on January 17. You can’t expect an institute to change on a dime. I liken this to an aircraft carrier making a turn. It takes a long sweep to move around. But,’ he adds, ‘I would invite you or anybody who wants to come see any of our classes.’

The colonel is keen to stress that human-rights instruction plays an important role in all courses now, though on the two days I spend at the academy there is no such instruction taking place. When I question the Salvadorian officer responsible for giving human-rights instruction to the most senior officers at the academy, he tells me he is referring fellow Latin Americans to lessons learnt from an investigation into the massacre of Vietnamese civilians by American soldiers at My Lai in 1968.

Why, I ask, not look at lessons learnt from tragedies closer to home – such as the slaughter of 900 men, women and children by the military in the Salvadorian village of El Mozote in 1981? ‘It is easier to study a situation that happened a long time ago and far away’ than discuss events that might ‘upset national sensibilities’, Lieutenant Colonel Julio Garcia answers vaguely, before excusing himself.

Despite Downie’s energetic attempts to promote his institute as forward-looking, tolerant and eager to support human rights, some of his staff appear slow to adopt his mantra. They clearly regard the academy’s bloody reputation as a joking matter. On one occasion, an American military officer interrupts my conversation with another member of staff, and advises the person I am talking to that he has ‘got somebody downstairs in the torture chamber’. Then, as I leave, another group of Americans in uniform lean out of a doorway and snigger that they are just ‘off to read those torture manuals’. A spokesman for the institute later describes such comments as ‘regrettable’.