August 6, 2006

August 6, 2006

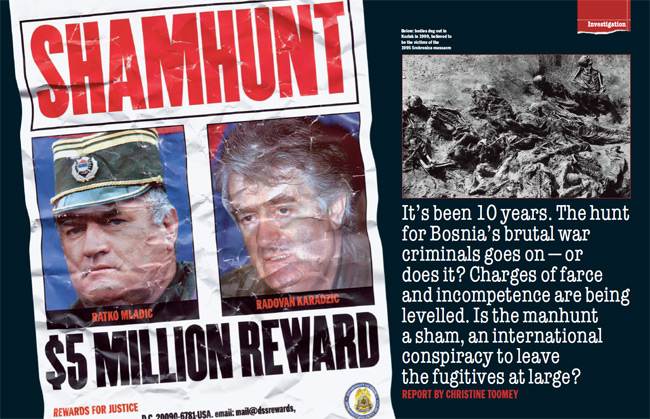

Investigation

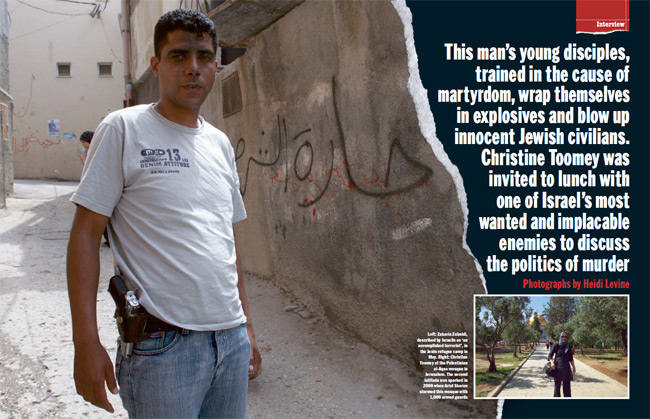

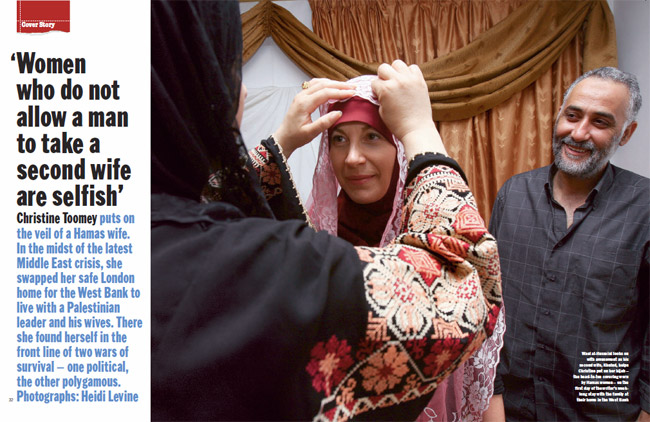

Christine Toomey, winner of Amnesty International’s 2006 award for best magazine article, puts on the veil of a Hamas wife. In the midst of the latest Middle East crisis, she swapped her safe London home for the West Bank to live with a Palestinian leader and his wives. There she found herself in the front line of two wars of survival — one political, the other polygamous

The two wives were suspicious at first. Their husband, Wael al-Husseini, had tossed a coin in the direction of his eldest son and, tongue in cheek, instructed him to go and buy an extra mattress. The women, I sensed, did not find the gesture as amusing as did the husband they shared. With it an extraordinary agreement was sealed. I was to return to live with the family, a third woman in a Hamas household, to tell the story of Hamas women, hundreds of thousands of whom, like these two wives, had voted Hamas into power – an election victory that slapped Israel in the face.

Their husband, Wael, had been elected to the Palestinian parliament in the spectacular Hamas victory in January, and it is wives and mothers like them who are the key to understanding why the Islamic movement –condemned internationally as a terrorist organisation – has been propelled into power.

When Palestinian women voted for Hamas in record numbers – a vote certain to lead to confrontation – few expected it. That religious women, long ignored as “silent walking tents”, were finally flexing their electoral muscle, was put down to widespread frustration with the corruption and incompetence of Fatah – the faction once led by Yasser Arafat that dominated Palestinian politics for 40 years – and also to a Hamas election campaign targeted at female voters. But there was more to it than that.

Many believed the peace process was already dead and, as one analyst observed, “When people lose hope in reality, they turn to God.” There was no way of knowing, when I first met the al-Husseini family, that in the time I would spend with them I would soon discover why so many women have become, in the analyst’s words, “hooked on Hamas”.

Hamas was then observing a ceasefire. No suicide bombers had been sent by the group into Israel since the former underground movement suspended such terrorist tactics last summer in an attempt to build an image fit for mainstream politics. Newsreel of the 10-year-old Huda Ghalia clutching her head in grief as she circled the bodies of her dead family, killed by Israeli shells as they picnicked on a Gaza beach, had yet to flicker onto television screens around the globe. Israel still disputes responsibility, but the next day, Hamas declared its ceasefire over, and set in train the events, with the kidnapping of the Israeli Corporal Gilad Shalit, that have since plunged the Middle East into open warfare with the bombing of Lebanon. When I entered the al-Husseini home to live as a “Hamas wife” – hours after the kidnapping – the region had yet to descend into the violent maelstrom that has followed.

“Wael is leaving the country. He has to attend a conference in Lebanon. He is not sure when he’ll be back. Come tonight,” my interpreter had urged me. That a Hamas politician was attempting to embark on a trip abroad as the eye of the storm approached seemed suspicious. Yet there were few signs of tension when I arrived at the family’s home in Ar-Ram, near Ramallah in the West Bank.

A breakfast of hummus, falafel and bread had been laid out. The family was relaxed as we sat down to eat, even though Israel was then on the verge of moving its tanks into Gaza. I could not believe a member of Hamas would be allowed to leave the country. But Wael was confident. He planned to drive east to Jericho and board a bus to leave the West Bank by crossing the Jordanian border. I was to go with him as far as the border, and then return the next day to stay with his wives and children.

From the start, the family was open about their domestic arrangements. They live in a spacious two-storey concrete home built by Wael to accommodate his expanding family by the side of the madrasah – an Islamic school for 600 pupils – of which he is headmaster. His second wife of two years, Khulud, 35, and their six-month-old son, Hamzeh, live on the top floor. Alia, Wael’s first wife of 20 years, who is 10 months younger than Khulud, lives on the ground floor with her six children: three girls – Ni’mah, 17, Arwa, 16, and Bara’a, 6 – and three boys – Khaled, 15, Seif, 12, and Omar, 10.

In accordance with Islamic teachings, which stipulate that if a man takes more than one wife – and he can take up to four – he must give to each the same material support and attention, Wael spends one night upstairs with Khulud, the next downstairs with Alia, in strict rotation. “Everyone is happy,” says the 43-year-old Wael with a gleam in his eye. The truth is, there is a much more complex interplay of emotions at work. These are revealed as any misgivings Alia and Khulud might have had about their husband welcoming me into their home evaporate.

At the start, as expected in such a male-dominated society, it is Wael who does all the talking. The second eldest of five brothers and six sisters born in Bethlehem, he talks of how his brothers persuaded him to study engineering in Saudi Arabia, rather than medicine in Romania, “where he might be too tempted by beautiful women”. It was in Riyadh in the early 1980s that he became interested in the Muslim Brotherhood movement, from which Hamas would later spring. After working briefly as an engineer on his return to the West Bank, he opened an Islamic school and became involved in community activities, such as “planting trees and sweeping streets”, organised by the Islamic resistance movement Hamas.

Initially a non-militant movement, Hamas was widely believed to have the tacit support of Israel to counter the then popular nationalist and leftist groups belonging to the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO). But as soon as the group began to threaten Israeli security with violent resistance, the arrests started.

Despite, he insists, being involved in only grassroots community activities, between 1988 and 2005 Wael was arrested eight times and held in “administrative detention” – imprisonment without charge – for more than two years. In addition, in 1992, he was among more than 400 Palestinians with links to Hamas deported by the Israelis for a year to live in tents in a no man’s land in Lebanon in an effort to break the back of the movement.

Wael claims that on the journey, Israeli soldiers guarding them would urinate into plastic bags and then spray the contents over the prisoners, whose legs were chained to the seats of the bus.

As his wives and children sit listening, Khulud turns to me and confides: “This is the first time I hear such things. Stay as long as you like. Keep asking questions. If there is one thing I find difficult about Wael, it is that he is so secretive.” She flashes a smile in his direction.

At this, Alia catches my eye and looks resigned. “Not once was Abu Khaled present when his sons were born. He was in jail each time,” she says in a soft voice, using the Arabic term “abu”, meaning “father of”, in contrast to Khulud’s more familiar use of her husband’s first name. Not to be outdone, Khulud explains that when Wael was last arrested in September 2005, “I was not used to him being in prison.

I cried all the time. I went crazy because I love him,” she declares, to which Wael coos in appreciation. “No, it is I who cried more,” Alia interrupts, a steely note to her voice this time.

This exchange between the two women is the first sign of their underlying rivalry. What neither know is that during the hours I spent with their husband at his office that morning, he had spoken candidly of how he plays with their jealousy. “Alia tells me all the time, ‘You love Khulud more,’ while Khulud says, ‘You love Alia more.’ This is what keeps me going. This way I am in control,” he confides, with a broad smile. “Alia and Khulud compete with each other in trying to cook me the best meal and in the way they dress and behave.”

Much of the time the women remain covered in their hijabs, the head-to-toe coverings they delight in showing me how to wear, but when not, have on jeans and T-shirts. Khulud highlights her hair. Newly married, she seems more eager to impress. Basking in her adoration and the efforts of his first wife to compete for his attention, Wael sees no irony in his insistence that “women who do not allow a man to take a second wife are selfish”.

When I tell him that his flirtatious sense of humour does not fit the popular image abroad of Hamas fanaticism, his hackles rise. “The stereotype of a Hamas politician is as a terrorist – aggressive, uncivilised and a liar. Yes, there are extremists in our movement, just like there are extremists in the West. But to the West we are all al-Zarqawis and Bin Ladens.”

When I challenge Wael on the subject of suicide bombers, his reply is even more surprising. “I hate them 100%. They are mistakes. I hate that innocent civilians die in such acts, and I believe we will suffer a divine punishment as a result. Islam is clear that civilians should not be killed. But these are desperate acts by those who see no alternative. We are denied recognition as a state. We have no army. So every attack we launch on Israel is denounced as terrorism, while every attack they launch against us, in which so many innocent women and children die, is justified as legitimate military action.”

Hamas has launched more than 40 suicide-bombing attacks against Israel in the past 10 years, but Wael claims he has no knowledge of the movement’s military wing, the leadership of which is based in Syria. Yet on the journey to Jericho the next morning, he reveals that his eldest brother, killed in Jordan two years ago, was the head of a military cell of Hamas. At this, another of his brothers who is with us confides that he was once told by the Israelis that “they consider Wael more dangerous than our elder brother, because he is an intellectual… because he is so respected, he has great influence”.

It is little surprise then that, after being kept waiting at the border by Israeli guards for many hours, Wael is turned back, and returns home.

The hollow eyes of Alia and Khulud and ashen faces of their children bear witness to the trauma of the night before, when I meet them the next morning. Bara’a is in a state of shock as she wails: “Has Daddy gone? Why have they taken him?” The answer is both so simple and so complex that her mother says nothing. She simply hugs the girl close and sits in stunned silence.

It is left to Ni’mah to explain that her little sister had, incredibly, slept through the night when dozens of soldiers surrounded the house, pounding on the front door, shouting her father’s name and kicking open the back door of the family’s home just after midnight. She had not witnessed her father being forced to dress hurriedly at gunpoint in an upstairs room and then pushed downstairs into a waiting Jeep.

Only Khulud had witnessed the whole drama. That night had been her turn with her husband. She speaks in a faltering voice, her eyes red from crying, as she describes what happened. “Wael shouted to the soldiers from an upstairs window that there were children in the house, that they must take care not to harm them; that he would open the front door if only they would stop trying to break it down. He shouted to me to get him some clothes. When I brought him a nice shirt he laughed and said, ‘Where do you think I’m going, to a party?’”

That night, dozens of similar raids had been carried out across the West Bank in a blitz attack on the Hamas-led government. One third of the Palestinian cabinet – eight ministers, including the deputy prime minister – 20 MPs and more than three dozen municipal leaders had been seized from their homes and herded into a jail near Ramallah.

When there is still no sign of the kidnapped Shalit being released, the Israelis ratchet up the retaliation further. Air strikes are launched on the Gaza strip and rumours abound that the Israelis will soon move on the West Bank. Huge crowds flock to Friday prayers at mosques close to the al-Husseinis’ home in Ar-Ram and elsewhere. Fighting breaks out in Nablus to the north and, like everyone, I sleep fitfully. But the brunt of the Israeli offensive is reserved for Gaza. In the two weeks that follow, more than 60 Palestinians, including many women and children, are killed in continual shelling. One Israeli soldier is killed by friendly fire.

In the aftermath of the arrests, and with the violence escalating, I feared the last thing the family would want was a stranger in their midst. After his arrest, Wael’s two younger brothers, both surgeons, took charge, ordering that neither Alia nor Khulud, nor any of the children, should leave the house. That the family would see my presence with them as protection against further retaliation, however, proved more to the point. Not only was I invited to return to stay, but in the days that followed, they opened up to me in the absence of their husband.

When the family finally exhausted their description of Wael’s arrest, and Khulud and the children went to rest, Alia sat with me in a state of agitation. Her distress poured from her like a burst dam. For Alia it was not just the events of the night that had traumatised her. She was deeply upset that when she tried to embrace Wael as he was being bundled out of the house, soldiers pushed her away with their automatic rifles. “They did not realise I was his wife,” says Alia. “This for me was the worst.”

She hesitates only a moment before carrying on. “Abu Khaled got married when I was in hospital in Nablus recovering from an operation. I had scalded myself with water while making coffee for the children. I had third-degree burns and needed a skin graft. I knew nothing about the marriage. When I came home and found he had taken a second wife, I was in great shock. It was the most difficult thing for me.”

()

When she tried to leave to return to her parents, Alia says her husband’s family, in particular her mother-in-law, prevented her.

“I raged and screamed and said things I did not know I could say,” Alia explains, before talking of the distress of her children, none of whom attended their father’s second wedding. “Seif sat with a blanket over his head for days,” she says.

The reason Wael took a second wife, he told Alia, was “so that she [the second wife] could help with the housework”. But then Alia discovered that Wael had rented an apartment where he intended living part of the time with Khulud initially. “I begged him to stay with me,” says Alia. “He said he would stay the first two weeks. He stayed four nights. Then he went with her. But when he brought Khulud to meet me the first time, I did not cry. A miracle happened. I suddenly went very peaceful. I remained calm. That really got to her.”

Khulud’s version of events is rather different. She talks about how carefully she thought out a strategy to deal with what she clearly regarded as Alia’s passive aggression. Khulud had been married before, at 16. But when her husband divorced her after two years for failing to satisfy him, Khulud, unusually in such a society, forged her own path as a single working woman by opening a hairdressing salon, though she continued to live with her parents. “This experience meant I knew how to deal with all sorts of people. So I felt it would be easy to deal with the first wife. I heard she was a simple woman. She was aggressive with me at first. But I took it. I had, after all, come into her territory. I pretended to ignore her aggression. I think it was my strong character and independence that attracted Wael to me in the first place.”

Alia disputes this. “He only met her once before they signed the wedding contract. So I cannot imagine it was her character that he liked.” But she does admit Khulud has qualities she lacks. Little wonder. Unlike Khulud, whose second marriage came relatively late in life, Alia had been matched by her family with her husband when he was 24 and she was 14. “I was young. I didn’t know anything,” she says. “Khulud has mixed a lot with other people, heard their stories. She is more confident and, I admit, she is faster in doing the housework than me.

“Now I see my husband wasn’t interested in finding someone more beautiful. He just wanted to feel better. I love him and accept this as my fate. But I no longer feel I have a complete marriage with my husband. I kiss his socks when he goes upstairs to spend the night with Khulud,” she says, poignantly. “I find it very difficult when she calls him ‘my beloved’ in front of me.”

Khulud will later reveal that she did not know when she got married that the conjugal arrangement would be that Wael would alternate the nights he spent between her and Alia. “This is not easy for me either,” she says. Yet even on the nights Wael spends with Alia, she confides, he often comes to her floor of the house to rest in the afternoon “because it is quieter”. She and Wael also seem to laugh, touch and talk more, and it is hard not to conclude that Alia sees less of her husband than his new wife. Something she can hardly ignore since, though there is a shared main entrance, he has to pass the front door to her floor of the house to reach Khulud’s. During the day all these doors remain open so that the children can be with their father in whichever part of the house he is in, and the entire family eats together. But at night the doors are shut, turning the two floors into separate apartments.

Strange as such arrangements may seem, when secular Palestinian women have taken to the street in the past to protest against the practice of polygamy – according to official figures, practised by just 3% of the population, but believed to be more widespread – as “demeaning to women”, those involved in such relationships, like Khulud and Alia, have condemned them as narrow-minded. In the West, men take mistresses or divorce their wives – polygamy is more moral, they argue.

For although the two women confess their anguish about their shared marriage to me privately, in each other’s company they insist they get on “like sisters”.

During the days and nights I spend with them, I see how calmly the two women share out their domestic chores. The rhythm of the household revolves around them putting on a special hijab to pray with their children in an upstairs room five times daily. Alia does most of the cooking, Khulud the laundry. And while it is Wael’s task to shop for groceries, in his absence, this chore, as well as financial responsibility for the household, is passed to his second wife, Khulud. Alia is given only a small allowance.

Alia’s life seems much more restricted than Khulud’s. When, for instance, she tells her brothers-in-law, who took charge of the house after Wael’s arrest, she wants to visit her parents in Nablus, she is quickly rebuffed. Yet Khulud goes unchallenged when she announces it will help her feel better if she spends a day in the salon she has reopened.

So the following day I accompany Khulud to her salon in a neighbouring village. It is a tortuous journey. Although the village of Qatanna can be seen from a hilltop in Ar-Ram, and the trip to work used to take Khulud only 10 minutes, since the recent construction of what the Israelis term an “anti-terrorist separation barrier” – a towering concrete wall with electrified barbed wire that snakes for 400 miles through the West Bank and which has been judged illegal by the International Court of Justice in the Hague – the journey can take hours. As the series of buses I take with Khulud zigzag their way back and forth avoiding the wall, it is clear what a blight this barrier casts over the lives of Palestinians, slicing communities in half, dividing families and cutting many off from their places of work.

We also have to negotiate our way around the many Israeli “security roads” – high-speed links between settlements that Palestinians are banned from using – and encounter “flying checkpoints”, random roadblocks erected by Israeli soldiers to either stop traffic temporarily or seal off entire areas at will. “I’m not sure I can carry on doing this much longer,” says Khulud as we reach our destination. “So many people have lost their livelihoods like this. Our lives are being made impossible. No wonder there are those who explode with rage.”

Such frustration underlines the sense of hopelessness about the lives of Palestinians, in particular those of women, who bear the brunt of the consequences of the war. When I ask Khulud and Alia what future they see for their children, they say they want them to study, find good work, have families, have a happy life. “But what chance is there of that?” says Khulud.

When, together with Alia and Khulud, I look at pictures of female Hamas supporters wearing the green headbands favoured by the movement’s fighters, they both say they admire the women. “They are strong. I like it. If I had the opportunity I would dress like that,” says Khulud, who, when she then sees a photograph of a baby wearing a military-style balaclava while chewing on a toy grenade, says if the Israeli occupation continues she would like to see her son dressed like that too. “Sometimes as I rock Hamzeh I wish he was old enough to carry arms,” she declares.

With such wishes transmitted to the young, what hope is there of peace? As in any culture, hopes and values pass through a mother’s milk. With this in mind, I meet Wael’s mother, who looms so large in Khulud’s and Alia’s lives, and, it seems, who calls the shots. A few hours in her company are all that are needed for the dynamics of the family, personal and political, to fall clearly into place.

A cool evening breeze rustles the olive trees surrounding the house where Wael’s parents live with his two younger brothers, their wives and five children. The building is set within the walled compound of the madrasah where Wael is headmaster. His mother sits in an armchair and I approach her with some trepidation.

With one son killed and another in prison in a conflict for which – Wael’s mother reminds me – Britain bears historical responsibility, I am not expecting a warm reception. But Arab hospitality prevails. The wife of one of Wael’s brothers brings pear juice while his mother calls the other daughter-in-law to bring her a wrap. The old woman seems to be sizing me up. She squints at me for some time before speaking.

It is about Alia that Wael’s mother, called Ni’mah, soon begins to talk. “Alia was very young when she got married and naturally we thought she would mature. As a wife gets older she should improve in satisfying her husband’s requirements. But this did not happen.

“It is only under extreme conditions that a man takes a second wife. It took a long time to agree with Wael that it was the solution. But Alia should have been more attentive to her husband. A man needs attention. Wael likes organisation. He likes to look elegant. Khulud is a distant relative and so I have some control over how she behaves. If a husband takes a second wife, it is she [the first wife] who is guilty. If anyone is not capable of being a perfect wife to my son then they should be worried,” she huffs. From the way she speaks and what Wael has confided earlier, a “perfect” wife is one who is not only constantly mindful of her husband’s needs, but also a fast worker and frugal when managing the household.

Sitting opposite me as Ni’mah speaks are her youngest sons and one of their wives. When I glance at the young wife to see her reaction to this declaration, she is sitting on the edge of her seat, hands clasped, staring straight ahead as if to avoid attention. My heart goes out to her.

“I love my children very much,” Ni’mah continues. Her slight-framed husband, who has never taken a second wife, sits silently perched on a hard chair by her side. “I have always encouraged my children to be both patriotic and religious.” She goes on to describe how her family was expelled from a large land-holding near Jerusalem that had been theirs for generations, when the British withdrew from Palestine and the state of Israel was founded in 1948. “The word of God is more important than my children,” she declares. “And God says we should perform jihad to reclaim our land from those who took it. So if God insists I must sacrifice my children, I will do it.”

As I say my farewells to Alia, Khulud and their children the next morning, I have a deeper appreciation of the trials they face. A female Hamas MP, whose imprisoned husband has also taken a second wife, describes dealing with both situations in equally warlike terms. “Polygamy is like fighting a war,” she says.

“A fighter goes into war to defend his country knowing he might die, but does so for a noble cause; and God orders us to accept this. So I feel when I accept polygamy I am a fighter too, implementing God’s will, however hard it might be.” The “noble cause” of her personal battleground she defines as “the enjoyment of men and women”. But it is hard not to conclude that men enjoy the outcome of such intimate conflict a lot more than women.

While Wael languishes in jail, Alia and Khulud are left wondering to which wife he will return the first night he is released. The last time he was imprisoned, Wael was in such a quandary about treating both women fairly when released that he sought the advice of a religious leader. He was advised to return to the bed of the wife whose company he had not enjoyed on the night of his arrest: in that instance, Khulud.

Since this time Wael was arrested so soon after going to bed with Khulud, she hopes he will return to spend the night with her again. In keeping with her gentle nature, Alia is resigned to this prospect.

“I just want him home,” she sighs. “How can you raise children under such conditions, with their father constantly taken from them? All that is left is for us to put our faith in God and, for us, that means Hamas.”