November 13, 2005

November 13, 2005

Investigation

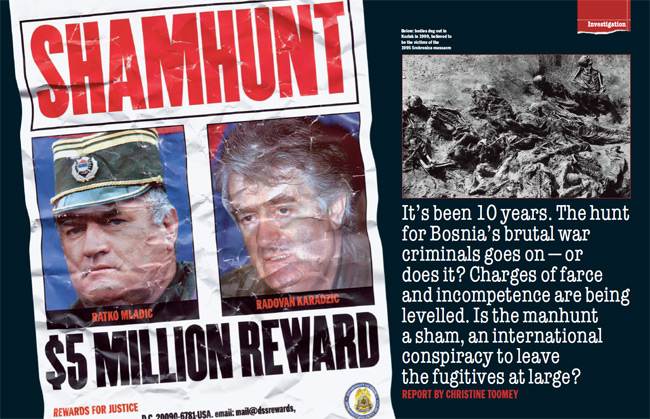

It’s been 10 years. The hunt for Bosnia’s brutal war criminals goes on – or does it? Charges of farce and incompetence are being levelled. Is the manhunt a sham, an international conspiracy to leave the fugitives at large? Report by Christine Toomey

As we round a bend in the road, after crossing the border from Bosnia into Montenegro on almost impassable logging tracks, the silence of the remote Durmitor mountains is broken by the sound of a mechanical digger. In the distance a group of men work with pickaxes and shovels alongside a small bulldozer. When our car draws close, they seem startled, down tools and move as one in our direction. Behind them, it appears they have hewn out of the rock face the beginnings of a stage and tiered seating.

When we walk towards the men, they quickly surround my interpreter and me, and demand to know who we are and why we have come. Few strangers venture into these parts and those who do are rarely welcome.

Many of the men share a common surname: Karadzic. All are relatives of Europe’s most wanted war criminal: Radovan Karadzic, the bouffant-haired former Bosnian Serb president charged with genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in the Hague. Extraordinarily, what these men are building is a venue for a literary festival to be held in his honour.

For the past 10 years, Radovan Karadzic and his chief military henchman, Ratko Mladic, have been at the top of the Hague’s wanted list as chief architects of the savage 1992-5 war in which over 200,000 people, mostly Bosnian Muslims, were raped, tortured and killed. As the smaller fry responsible for such ethnic cleansing have gradually come to trial, the two men held most responsible for the worst war crimes committed in Europe since the end of the second world war remain at large. I have set out to discover why.

This is Petnjica, the small village where Karadzic was born. There are more than a dozen families here bearing the Karadzic name. What greets us is perhaps the ultimate symbol of the folly and denial of those who continue to support both Karadzic and Mladic. It is a folly matched by the incompetence of international peacekeepers, others within the international community, and government authorities in the region, who defiantly declare they want both men brought to justice, yet have allowed the decade-long manhunt to descend into farce.

The longer this farce continues, the more it is interpreted by those with an interest in rewriting history as evidence of the lack of a case to answer. For the Karadzic clan, however, history has always been seen through a warped prism. ‘Radovan is a good man. He did what all of us would have done to defend our fellow Serbs,’ says Tomislav Karadzic, older cousin of the former head of state. The stooped 63-year-old shakes his head as he leads us across fields for coffee at his farmhouse. ‘It’s very hurtful what they say,’ he complains, refusing to hear of the charges laid against the man he recalls playing with as a child. In the words of one of the ICTY judges, these charges relate to ‘scenes of unimaginable savagery… truly scenes from hell, written on the darkest pages of history’.

One of two counts of genocide faced by both Karadzic and Mladic stems from the July 1995 slaughter of an estimated 7,500 men and boys in Srebrenica in which, the indictment states, ‘Men were buried alive, women mutilated, children killed before their mother’s eyes… a grandfather forced to eat his own grandson’s liver.’ Yet Tomislav insists: ‘I’m proud to call myself a Karadzic. This is a noble family: we have produced dukes and warriors, writers, heroes.’ On the wall hangs a family tree dating back to 1642, with hundreds of names. He points out one central character to whom his cousin is directly related: Vuk Karadzic, a well-known 19th-century Serbian writer, who drew up a system of phonetics fundamental to the Serbo-Croatian language. ‘Radovan inherited his literary talent. That is why we are building a venue here for a biennial international Karadzic literary festival.’ The first phase is due to be finished this month, he says, after which there will be an inauguration. ‘We expect schoolchildren and international visitors, once the festival is launched. And if God is just, Radovan will, one day, be able to attend,’ says Tomislav of the man on whose head the US government has placed a $5m bounty. When asked when that might be, Tomislav stares broodily into the distance.

‘The mountains and caves around here have protected Karadzics for more than 500 years,’ says Simeun Karadzic. ‘They will never give up their secrets – least of all to you. You probably have family in the armed forces who dropped bombs on our children in Belgrade. Let me show you something that hangs in the house of every good Serb family, and you will understand why nobody is a traitor.’ Karadzic and Mladic beam out from photographs above the September-October page of a 2005 calendar. The curse that runs alongside reads: ‘Whoever betrays these heroes, let his heart explode. Whoever says where they are, let him eat his own bones. Let him answer to God for his deeds. For in his family there will be neither marriages nor celebrations. And no more males to carry guns.’

‘Why is it only Serbs are blamed for what went on? There was killing on all sides,’ says Simeun, ignoring the fact that Croat and Bosnian Muslim soldiers face war-crimes charges in the Hague too. He then takes us on a tour of the building site, pointing out areas that will be planted ‘with national flowers, not Dutch tulips or English grass’. Neither Simeun nor Tomislav will disclose where the money is coming from for this scheme in such a poor village, except to say there are ‘benefactors who make donations’.

Amid all the boasting, the two cousins provide a crucial insight into the man who ordered the citizens of Sarajevo to be starved of food and sniped at for three years.

He comes from a family accustomed to violence. ‘All Karadzics are like wild animals. But Radovan’s father was not only harsh, he was dangerous,’ says Simeun, though he stops short of mentioning that Radovan Karadzic’s father was ostracised by his family after being accused of raping and killing a cousin, and that his grandfather murdered a neighbour in an argument over stolen oxen. To escape this violent childhood, no doubt, Radovan Karadzic, a bright student, left Montenegro for Sarajevo, to train first as a doctor and then as a psychiatrist, and write poetry. He portrayed himself as a sensitive bohemian; work colleagues remember him anxiously biting his fingernails until they bled, and locking himself in his office when confronted by agitated patients. It was after he had been jailed briefly for embezzlement in the mid-1980s that he modelled a career for himself as a dangerous demagogue.

As the communist state of Yugoslavia crumbled in the early 1990s, Karadzic helped set up the Serbian Democratic party (SDP) when Bosnia was struggling for independence. The SDP supported the goal of a ‘Greater Serbia’, uniting all Serbs in the disintegrating state, as did his mentor Slobodan Milosevic, then president of Serbia. As both whipped up Serb nationalism, turning it into a murderous frenzy, Karadzic declared himself head of the independent Serbian republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and set about ‘cleansing’ it of Croats and Bosnian Muslim.

More than a decade later, Milosevic is sitting in a courtroom at the Hague, charged with war crimes in Kosovo and Croatia, and genocide in Bosnia. Both Serbia and Republika Srpska – the vast swathe of territory to the north and east of Bosnia ceded to the Serbs by the Dayton peace accords – are regarded internationally as pariah states, and their people have been left struggling for economic survival. As a result, support for Karadzic is on the wane. In most of Republika Srpska, it is only those in the still-functioning SDP, which many view as Karadzic’s private protection racket, who openly back him.

Except, that is, in this mountainous corner of northwestern Montenegro where he was born, and in remote communities in southeastern Bosnia, where he is still revered and so is believed to move about with ease.

While Karadzic has been losing the support of his fellow Serbs, many have excused Mladic on the grounds he was a professional soldier doing his master’s bidding. But, as with the Karadzic clan, there is widespread denial of the truth of what happened during Bosnia’s brutal conflict.

Milica Avram, Mladic’s 65-year-old sister, improbably insists she has neither seen nor heard from her brother in years. ‘If he was a bad man, it would not be so hard to bear. But he is a great man. He did nothing he is accused of. He was the one handing out sweets and chocolates to children in Srebrenica. He never wanted to be a soldier, he wanted to be a doctor. But where we grew up, he had no chance of an education unless he entered the military,’ says Avram, who lives in Vojkovici, on the road from Sarajevo to Foca, the town where Karadzic and Mladic’s men operated one of the most notorious rape camps during the war. When we travel further along the road to Foca, and take a detour into the Treskavica mountains, it is easier to see what she means.

‘There used to be a saying in the army: ‘If you step out of line, you’ll be sent to Kalinovik,” our driver says, manoeuvring onto yet another dirt track beyond the small town of that name. The hamlet of Bozinovic, where Mladic was born, is further on, across a rocky moonscape dotted with the rusting hulks of cars on which black crows perch. Mladic’s relatives turn their backs and curse us when we ask when they last saw the general. Jovo Mandic, an elderly neighbour, shakes his fist and shouts:

‘We would all kiss him and hide him if he came here. I would give my life, my own child, to save him. He is a national hero!’ Such sentiments are echoed by many we speak to across Republika Srpska. ‘It is not possible he is a war criminal. He was a good communist,’ says his former driver, a grocer in the northern town of Han Pijesak. ‘Though maybe, following the death of his daughter, he lost his grip a little,’ he adds. Others claim that Mladic’s blood lust increased after the suicide of his only daughter, Ana, who killed herself in 1994 after reading accusations about her father’s brutal war record. The 23-year-old medical student shot herself in the head with a gun that her father had sworn should only be fired to celebrate the birth of his grandchildren.

Yet since the release, last July, of video footage of the murder of a group of Bosnian Muslim men from Srebrenica – 10 years after the slaughter – Serbs are beginning to change their minds about Mladic. The footage shows six terrified prisoners, some in their teens, being hauled from a truck by Serb paramilitaries and subjected to a mock execution before being led into the woods and shot. Until 2002, however, eight years after being charged alongside Karadzic with genocide and other crimes against humanity, Mladic was still receiving a full military salary from the Serbian government, and until two years ago he was on the payroll of the defence ministry of Republika Srpska. Even now he receives a pension of about e400 a month from the government of Serbia and Montenegro – money collected by his son.

With the support networks for Mladic and Karadzic so clearly defined, and the circles, even some geographical areas, within which they have been moving known, it’s no wonder there is such anger about the ongoing failure to capture them. The EU has insisted that talks for Bosnia-Herzegovina to join the union don’t start until both men are behind bars at the Hague. This has left the country with seriously stunted political development, low growth, high unemployment and pervasive corruption.

The woman whose regular proclamations about imminent arrest particularly anger Bosnians is the ICTY’s fist-thumping Swiss-born chief prosecutor, Carla Del Ponte. Yet, apart from a small number of investigators on the ground in Bosnia, the tribunal Del Ponte joined in 1999 lacks a police force of its own, making it reliant on international peacekeepers and the authorities of the former Yugoslav republics to hunt the men down and deliver them to the Hague. For years these various organisations – including Nato, Eufor (the 7,000-strong EU force), the US and EU police missions and intelligence services, the Bosnian and Republika Srpska police and intelligence agencies, together with those of Serbia and Montenegro and Bosnia’s state border service – have been pointing the finger of blame for failure at each other.()

In the immediate aftermath of the war in Bosnia, Nato commanders excused their lack of success in arresting war-crimes suspects by citing fears that such arrests would destabilise the region. This led to farcical situations in which Karadzic, Mladic and others were waved through Nato checkpoints without being stopped. Later, this excuse shifted to a desire to minimise reprisals against Nato soldiers attempting to apprehend the wanted men – so-called ‘force protection’. Most Bosnians are convinced the real reasons for the lack of arrests are behind-the-scenes deals struck by Nato with Mladic and, in particular, Karadzic, to bring the conflict to an end. Karadzic has boasted he was assured by the US envoy at the time, Richard Holbrooke, that as long as he retired from political life, he would be left in peace. Following on the trail of bungled attempts to seize both men, it is impossible not to believe that there is some truth in this.

High in the mountain village of Celebici in southeastern Bosnia, somebody switches off the light in a wooden house and refuses to answer the door when we approach as dusk falls. ‘We know nothing, we think nothing,’ says an old woman, sullenly serving beer to a forestry worker and a hyperactive teenager in a small shack that serves as a bar. ‘Why would anyone come to a place like this where even we can hardly survive?’ she says when asked if she knew if Karadzic had ever been in the area.

‘Yes, I saw him: he was here. He runs a drugs ring here,’ the teenager contradicts her. What he says is not completely far-fetched. Lucrative deals in black-market cigarettes, whisky and petrol, together with drug-trafficking and illegal logging, are believed by those on the trail of Karadzic and Mladic to provide the financial underpinnings of their support networks.

Certainly, Nato believed he was here three years ago when, early one February morning, four US helicopters swooped low, and military transport vehicles pulled into Celebici. Both disgorged more than 100 masked Nato soldiers, who moved from house to house here and in neighbouring hamlets, banging on doors and arresting and interrogating villagers for two days. They repeated the operation six months later.

Looking out across the vast stretches of wooded mountains that surround Celebici, it is clear that if Karadzic had been anywhere in the vicinity as the Nato troops approached, he would have had ample warning and time to escape into Montenegro. The border lies less than a kilometre away, and it has taken us over two hours to pull our car along the deeply potholed mud track that leads here from Foca.

Another attempt by Nato forces to arrest Karadzic was staged in an equally high-profile but equally unsuccessful operation in Pale, near Sarajevo, last year. Acting on information that Karadzic was ill and seeking medical help, Nato troops stormed a priest’s house, but no trace of Karadzic was found. Since then, there have been repeated raids on the homes of his wife, Ljiljana, and daughter, Sonja, in Pale, and in July his son was arrested for questioning. Until last year these houses were guarded by French troops attached to the Nato force. As well as the deal Holbrooke allegedly struck with Karadzic, there have long been suspicions that the French continued to protect him because of their traditional ties with the Serbs. Some claim that French soldiers would make no mention, until a day or so after Karadzic’s wife had left her house, that she was going on trips – trips she is now understood to have been taking to see her husband.

Letters seized by Nato forces during one of the raids on her home show that Karadzic has continued to correspond with his wife and to receive clandestine visits from her while on the run. In letters written between January 1999 and December 2002, passed to his wife by couriers, he talks of arranging meetings: ‘Now summer is practically here, everybody is going somewhere, so it would not be a problem [to meet].’ Later, presumably after they have met, he jokes about his wife feeling unwell: ‘If I was younger, I would hope you were pregnant.’

While in hiding, he has also continued to develop his amateur literary career. In the past two years, an autobiographical novel, Miraculous Chronicles of the Night, has become available in the Serbian capital and Republika Srpska. He is also said by Sonja to have been working on a play called Situation – ‘a black comedy about a man chosen to become the leader of his people’, she says. A play he hopes, perhaps, to see performed one day at the Karadzic literary festival.

Some claim that Karadzic now spends much of his time disguised as an Orthodox priest, moving regularly between church properties on both sides of the Bosnia-Montenegro border. Monitored phone calls are said to have tracked him to a temporary hiding place in Montenegro’s Ostrog monastery. ‘Church is no place for politics. We are not hiding him here. Only God can protect him now,’ says Father Sergei, a senior priest at Ostrog. Other seized letters written by Karadzic, however, suggest he has been trying to involve the church in dubious property deals.

Mladic, meanwhile, is believed still to rely on the protection of his former military comrades.

Until three years ago, he was seen dining openly in expensive restaurants in Belgrade, and was spotted attending football matches. After Milosevic was sent to the Hague, and Mladic lost his political protector, he went into hiding and has rarely been sighted since. On the eve of local elections in Serbia in the summer of 2004, however, Nato sources say he sought refuge in a bunker complex at Han Pijesak, which once served as the general’s wartime headquarters.

Six months later, Nato troops swooped on the site and found the underground complex fully heated, with beds made and a kitchen fully stocked. In an operation code-named ‘stable door’, they ordered the bunker to be sealed off with concrete. When we visited in September, however, Serb soldiers standing guard at its entrance, and ordering us to leave immediately, gave no indication that the site had been closed.

In recent months there has been much speculation that Mladic would rather commit suicide than risk capture. Others claim that negotiations are under way with the government in Belgrade to persuade him to surrender to the Hague. A large amount of money is said to have been offered to his family if he hands himself in. To the outrage of most Bosnians, money is known to have been paid to the families of other, lower-ranking war-crimes suspects, partially explaining the large number of surrenders of wanted men – 69 in all, 24 in the past year. This brings to 126 those indicted for war crimes by the ICTY who have so far been sent to the Hague for trial – 25 of them arrested outside the Balkans, some in Russia and South America. As the number of war-crimes suspects wanted by the ICTY has dwindled – just seven, including Karadzic and Mladic, remain at large – the military brass with both Nato and Eufor bridle at accusations that their list of bungled operations amounts to serial failure.

‘Yes, it’s true the most wanted are still at large,’ concedes General Bill Weber, the newly arrived Texan head of Nato’s small remaining force.

‘But what’s interesting is that as the number of ÔPifwcs’ reduce, you can focus more of your attention and resources on the small number that remain.’ Pifwcs is an acronym for ‘persons indicted for war crimes’, but as a civilian at the base later pointed out, ‘It makes them sound more like cute cookies than criminals.’ Weber goes on to admit how the Americans really view it: ‘We just want to get this issue off the table now and move on. It’s been 10 years. It’s gone on long enough. How much longer can it go on?’

It is a question every Bosnian would like answered. But Weber’s comment sums up the increasing lack of interest most feel that the international community now shows towards the issue of arresting Karadzic and Mladic. The policy of Britain and the rest of the EU and the US has been a combination of carrot and stick; the carrot being the beginning of accession talks to the EU and membership of Nato’s Partnership for Peace programme, and the stick, a suspension of aid. But neither has worked so far when it comes to Karadzic and Mladic.

‘Bosnia has become a sideshow, an irritant, a nuisance, now that the focus is on Iraq and the war on terrorism,’ said one frustrated political consultant. Given the amount of intelligence there has been about the whereabouts of both men, he reflects the view of many that neither will be caught until it is considered politically expedient – especially by the authorities in Serbia, Montenegro and Republika Srpska.

Paddy Ashdown, the international community’s high representative in Bosnia, looks weary as he speaks of the need for the hunt for Karadzic and Mladic to be viewed as a ‘long campaign, not a series of commando raids. Until now the policy of the international community has been the policy of the lucky break. What you have to do to catch him is change the perception of the people who provide him with support’.

To this end, Ashdown has concentrated his efforts on launching Operation Balkan Vice to crack down on the organised-crime networks that support Karadzic and Mladic. He has frozen the assets of many of those involved and sacked dozens of officials, including Bosnian Serb politicians and police accused of impeding the hunt. ‘You can’t have stable peace without justice, and you can’t have justice until the primary architects of this horror are brought to trial,’ says Ashdown, whose term of office is due to end early next year. Whoever takes his place as high representative is mandated by the Dayton peace accords to continue pushing for the arrest of Karadzic, Mladic and other wanted war criminals. ‘Karadzic has famously vowed he will Ôhold on until the foreigners get bored, go away and leave us to our own devices’. But we will not go away until they are captured,’ says Ashdown. Weber’s assurance is more alarming: ‘I’d like to remind people that Simon Wiesenthal was still chasing war criminals 50 years after the end of the second world war.’ Bosnia may not have the luxury of so much time.

Aside from talks on the country’s accession to the EU and future economic welfare being conditional on their capture, some raise the spectre of renewed conflict if they are not caught. There has never been any doubt that the way Bosnia was carved up into a semi-autonomous Serb republic and Muslim-Croat federation – which share rotating positions of government authority – was unworkable in the long term. The longer Karadzic and Mladic remain at large, the greater the risk of those, especially within Republika Srpska and neighbouring Serbia, using such a denial of atrocities committed during the war to fuel dangerous tensions in Bosnia’s fledgling democracy. Suzana Sacic, a columnist with the Sarajevo weekly news magazine Slobodna Bosna, sums up the threat: ‘Evil politics are behind the fact that Karadzic and Mladic have been allowed to remain free. This has left this entire region in a dangerous vacuum. What would have happened if Hitler had remained on the scene, and been allowed to continue influencing Germany’s political life?’

Long day’s journey into darkness

Radovan Karadzic

1945 Born Petnjica, Montenegro

1960 Moves to Sarajevo

1968 Starts to publish poetry

1971 Graduates as physician and psychiatrist

1985 Imprisoned on embezzlement and fraud charges

1990 Helps found Serbian Democratic party

1992 Declares himself president of the independent Serbian Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina. During the ensuing war (1992-5), an estimated 200,000 are killed

1995 Indicted by the ICTY in the Hague for war crimes and crimes against humanity

1996 Forced to step down as president of the Serbian Democratic party after sanctions threatened against Republika Srpska

1996 International arrest warrants issued for Karadzic and Mladic on July 11, and Karadzic goes into hiding

Ratko Mladic

1943 Born Bozinovic, near Kalinovik, Bosnia- Herzegovina

1965 Graduates from military academy and rises rapidly through the ranks of the Yugoslav people’s army (JNA)

1991 Appointed commander of the JNA in Knin, Croatia, which had just declared independence. An estimated 20,000 die in

a seven-month war, during which hospitals are pounded with artillery

1992 Appointed commander of the Bosnian Serb army

1994 His daughter Ana commits suicide

1995 Aided by the JNA, leads Bosnian Serb forces to take the UN ‘safe havens’ of Srebrenica and Zepa. Televised patting children on the head; 40,000 Bosnian Muslims are then expelled from Srebrenica and an estimated 7,500 men and boys are executed. Mass graves are still being unearthed

1995 Indicted by the ICTY on the same charges as Radovan Karadzic. International warrant for his arrest issued the following year

2000 Seen attending football matches in Belgrade (including a friendly between Yugoslavia and China in March) and dining openly on steak and caviar in Belgrade restaurants, up until 2002 – several months after his political mentor Slobodan Milosevic is extradited to the Hague in 2001