August 26, 2007

August 26, 2007

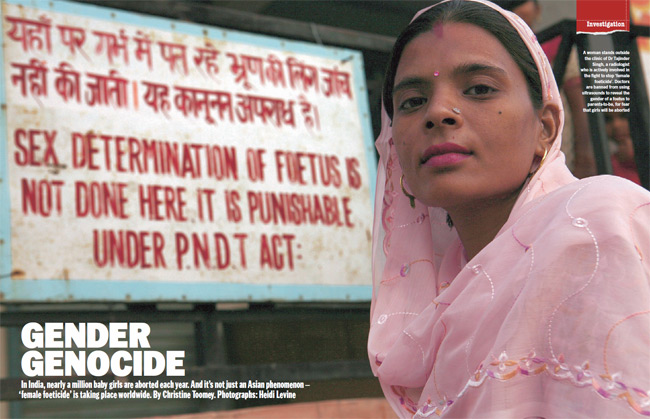

Investigation

In India, nearly a million baby girls are aborted each year. And it’s not just an Asian phenomenon — female foeticide’ is taking place worldwide. . Photographs: Heidi Levine

Dera Mir Miran is a village rich in buffaloes and boys. This small, prosperous farming community close to the foothills of the Himalayas saw the birth of four babies in the first six months of this year. Three were boys, just one a girl. The baby girl’s parents named her Navnoor, meaning “New Light”. But her mother wept because she was not a son.

Most of the families in this area of the Indian Punjab belong to the high-caste, landed Jat Sikhs. The family into which Navnoor was born manage a 37-acre plot of land growing mainly wheat and rice. Their house is spacious, built around an inner courtyard, shielded behind large steel gates and flowering bushes.

Navnoor’s mother, Jasmit Blaggan, moved in with her husband’s family when she married, as is the norm in India. She gave birth to her first daughter, Bhavneet, five years ago. When she became pregnant a second time, she did not, as many women do, come under pressure from his family to have an ultrasound scan to determine whether it was a girl or a boy. Her mother-in-law, who, like most mother-in-laws in India, wields considerable influence in the house, believes all children, boys and girls, are a blessing. But Jasmit, 30, took some convincing.

When her mother-in-law visited her in hospital after giving birth to Navnoor, she found Jasmit crying. “I was not happy that I had a second daughter. I thought about the cost of dowry and I knew a second girl was not needed,” says Jasmit, her broad smile softening the harshness of her words. “But then my mother-in-law said families used to have many more children, more daughters, and were happier then. I became calmer, but I do worry about what is to come.”

Jasmit is not alone in her concern for the future. Although sex-selection tests have been illegal in India since 1994, unwanted female babies are now being aborted on such a staggering scale that it is estimated India has lost 6 to 10m girls in the past 20 years, a large proportion of the abortions being carried out at five- to six-month term. While abortions have long been legal in India, choosing to terminate pregnancy because of the child’s sex is not. But such practice is now so widespread that some experts estimate the figure could soon rise to nearly 1m girls lost every year as a result of this “female foeticide”.

One recent Unicef report estimated that that figure had already been far surpassed, with 7,000 fewer girls born in India every day because of sex-selective abortion – though this calculation has since been questioned – amounting to more than 2m “missing girls” a year.

Not that those who choose to terminate a pregnancy for such reasons ever admit it. To do so would be tantamount to confessing a criminal offence, even though laws banning the use of ultrasounds to reveal the baby’s gender and sex-selective abortions are rarely enforced. Many doctors skirt the law forbidding disclosure of the sex of a foetus by using signals such as handing out pink or blue sweets or candles after an examination. Some families talk instead of “miscarriages”. Given the demographics of villages like Dera Mir Miran, it seems many such “miscarriages” must have occurred. Dera Mir Miran – population around 790 – is situated in a district called Fatehgarh Sahib, which in India’s last census in 2001 had the lowest ratio of girls to boys at birth of any district in the country. This census revealed that nationally the number of girls born per 1,000 boys was 927 (figures gleaned from a sample of 1.3m households in 2004 suggest this number had fallen in three years to 882). The natural birth rate globally is around 950; in China it is 832. But in Fatehgarh Sahib in 2001 it was 754, and in some villages less than 500. In Dera Mir Miran it was just 361.

Yet the word “miscarriage” only slips into conversation after I’ve been talking for some time with another extended Jat Sikh family in the village, that of Balvir Kaur and Joginder Singh, both now in their seventies. With a gaggle of girls and boys playing in their courtyard and several women gathered around, it is not immediately apparent that females are in short supply in this household. But it becomes clear that one branch, that which lives in the house – the rest are visiting – is overwhelmingly male.

This is the branch of Joginder Singh’s only son, Sukhpal; his four daughters moved away from home when they got married. Sukhpal had three sons, now in their twenties, and those sons also only had sons, four of them. “It is the will of God that only sons are born in this household now,” says Balvir Kaur, as her husband hovers in the background. “We don’t feel disturbed by this. The main reason is to keep property in the family. We have learnt how to cope. Earlier there was infanticide, now there is foeticide,” she says, quickly adding that this has not happened in her family. Only when Balvir moves away and leaves me briefly with her daughter-in-law Kulwinder, does a hint of sadness enter the conversation.

“I wish I had a daughter,” she says. “A woman feels awful without a daughter. Daughters help their mothers. I still feel sad about it,” she says, looking away. “But there were miscarriages.”

India is not alone in aborting a huge number of baby girls. The backlash to China’s long-term one-child policy, and determination of parents that this one child be a boy, have already led to such wildly skewed sex ratios that it is estimated 30 to 40m Chinese men – called “bare branches” – could fail to find brides by the end of the next decade, which some predict could lead to considerable social and political unrest Other affected countries in Asia include Pakistan, Nepal, Afghanistan and South Korea. But in India, where population growth now far outstrips that of China, with an estimated 25m births annually compared to China’s 17m – together these two countries account for about one-third of all births globally – the consequences of such distorted demographics could be even more dire.

While the Indian Medical Association and some anti-sex-selection activists claim the figure of India having “lost” 10m girls in the past 20 years – as published in the UK’s Lancet medical journal last year – is exaggerated, India’s government now admits it is a matter of great national shame. There are even those who, though not disputing a woman’s right to have an abortion, believe the extent to which female babies are now being eliminated on the basis of their gender amounts to genocide. Among them is Dr Puneet Bedi, a respected obstetrician specialising in foetal medicine and adviser to the Indian government, who likens what is happening in his country to a modern holocaust.

“Just as throughout history euphemisms have been used to mask mass killings, terms like ‘female foeticide’, ‘son preference’ and ‘sex selection’ are now being used to cover up what amount to illegal contract killings on a massive scale, with the contracts being between parents and doctors somehow justified as a form of consumer choice,” says Bedi, surrounded by photographs of his own two daughters in his surgery in New Delhi. He and others blame an unscrupulous sector of the medical profession along with multinational companies for flooding India with ultrasound machines over the past

20 years to exploit India’s traditional patriarchal culture, turning sex determination and selective abortion into a multi-million-pound business. In a country where paying dowries when daughters get married can be financially crippling, such tests and abortions, costing as little as a few pounds each, have been openly advertised in the past as “spend now to save later”.

That the West is beginning to pay more attention to such distorted demographics in Asia because of the potential security risk millions of testosterone-charged, frustrated bachelors could pose is deeply offensive, say activists. Yet the publication of a book by the political scientists Valerie Hudson and Andrea den Boer entitled Bare Branches: The Security Implications of Asia’s Surplus Male Population, three years ago, led to a flurry of news headlines and alarmist predictions of the “chilling” increased threat of war, crime and social unrest in China and India as a result. The book talks of the possibility that ever-increasing numbers of unmarried men in both countries will push Chinese leaders towards more authoritarian rule to control a marauding “bare branch” generation, and could threaten the stability of India’s democracy through a swelling population of rootless and marginalised males.

“For a long time the rest of the world condemned us as hyper-breeding, and pumped a fortune into family planning. So the West must now accept some responsibility for this situation,” says Bedi. But he and others believe fewer and fewer girls will be born in India and elsewhere until what is happening is recognised, on both a national and international level, as the most fundamental breach of human rights: that of a female child’s equal chance of being born.

Far from the shortage of women increasing their worth and standing in society, as some might imagine, the result is the opposite. Women are now being trafficked in increasing numbers from Indian states where sex ratios have declined less rapidly. Some are sold into marriage. Others are forced to engage in polyandry – becoming wife to more than one man, often brothers. Those that fail to produce sons are often abandoned, sometimes killed. This further perpetuates the cycle of prejudice and injustice, ensuring many women themselves prefer to give birth to a son to ensure no child of theirs suffers a similar fate.

Unicef recently concluded that “the alarming decline in the child sex-ratio [in India] is likely to result in more girls being married at a younger age, more girls dropping out of education, increased mortality as a result of early child-bearing and an associated increase in acts of violence against girls and women such as rape, abduction, trafficking and forced polyandry”.

While some might excuse what is happening as a result of poverty and ignorance in a country where, last year, gross national income per capita was less than £400 and an estimated 40% of the adult population is illiterate, again the opposite is true. It is not the country’s poorest but its richest who are eliminating baby girls at the highest rate, regardless of religion or caste. Delhi’s leafiest suburbs have among the lowest ratio of girls to boys in India, while the two states with the absolute lowest ratio are those with the highest per capita income: Punjab and Haryana. The joint capital of both states is Chandigarh – Dera Mir Miran is less than an hour’s drive away.

As we walk along the lanes of Dera Mir Miran, we pass a group of young men. Do they worry about the shortage of girls, I ask them. Most shrug and walk on. Only one turns to reply. “I’m not worried because I share five acres of land with my brother, so there are already two girls who want to marry me,” he says with a grin. “Only those without land or with personal problems will be left without wives.” An old woman passing by shakes her head and mutters: “I think most of the boys around here will be bachelors soon. It is very, very bad.”

By “personal problems” he means the increase in alcoholism, drug addiction and violent crimes against women that has accompanied the serious skewing of the sex ratio. In those areas where the sex ratio is worst, violent crime is increasing. It is a problem mothers such as Jasmit are intensely aware of. “I worry about my daughters’ future,” she says. “I know there will be more violence and rape as they are growing up.” Jasmit is unlikely to have more children owing to health reasons, so she is determined to ensure her daughters get a good education: “I want them to become teachers or doctors, then no one will pity me for having no sons.” Jasmit’s brother-in-law Manmeet, 22, says he wants only one child and would prefer a boy “because only sons inherit family property”. While Indian law bans dowry payments and gives equal-inheritance rights to daughters and sons, both laws are widely ignored. So parents want sons to keep wealth in the family; also, because sons traditionally remain in the family home to care for parents in their old age.

As India’s economy has strengthened and the country’s middle class expands, growing consumerism has increased dowry expectations to an average cost of between three and five years’ wages – sometimes 10 – according to Tulsi Patel, a Delhi university professor specialising in gender and fertility issues. “The higher the status of the boy, the higher the dowry. And it is not a one-off affair: the girl’s family continues to give gifts to her husband’s family throughout her life. It is very humbling to be the parents of a girl,” says Patel.

Despite the Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques (PNDT) Act banning sex-selective ultrasounds since 1994, it was not until last March that a doctor was jailed for flouting it. More than a dozen are now under investigation for similar offences. Others have been charged with carrying out illegal abortions under the 1971 Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, following such grim discoveries as that made recently in Pataudi, a town southwest of New Delhi. Acting on a tip-off, police raided a clinic there on June 13 and found eight half-burnt female foetuses five to six months old.

Female foetuses are often aborted relatively late in pregnancy because ultrasounds are rarely able to reveal the sex of a child before the end of the third month. Many parents, fearing they might abort a son by mistake, will deliberate for weeks, and sometimes go for a second ultrasound before seeking to abort a baby girl. The procedure commonly used to carry out the abortions involves injecting either a disinfectant, ethacridine, into the uterus or potassium chloride directly into the vital organs of the foetus, before premature labour is induced with prostaglandins.

Veena Kumari is all too familiar with the problems associated with violent discrimination against women in India. As a lawyer for the Voluntary Health Association of the Punjab, a nongovernmental organisation working with women and families on health issues in Chandigarh, she has a stack of files cataloguing brutality against women, including wives who refused to subject themselves to sex-selective ultrasound testing and then gave birth to girls. “Sex-selection tests are considered a status symbol,” she fumes, as she picks up a file detailing the alleged murder of a university graduate by her husband and mother-in-law – both now in jail awaiting trial – because she refused to have the test and gave birth to two daughters.

In the Shakti Shalini women’s shelter in Delhi we meet two other mothers whose husbands beat them and then abandoned them for not giving birth to sons. “My husband subjected me to much verbal abuse and torture, then left me because he said he was too ashamed to admit to his family that we had two daughters,” says 23-year-old Seema, as her two daughters, aged two and five, play outside. “My eldest girl talks about her father all the time. She says he is a good man. When she is older I will tell her he died.”

Low-cost, mobile ultrasound machines transported, even to villages without reliable electricity or running water, mean only the very poorest cannot afford sex-selection tests. This is why Kumari believes a baby girl abandoned at the Mother Teresa orphanage in Chandigarh, who we find fighting for her life in the city’s municipal hospital, probably came from an impoverished family.

The newborn girl had barely weighed enough to trigger the alarm as she was put into the basket set into the wall of the orphanage 10 days earlier. But the vibration of her cries had tripped a wire connected to a bell inside. By the time one of the Sisters of Charity reached the cradle, whoever had left the baby had disappeared.

Within hours the frail infant was transferred to the city hospital’s neonatal unit. Standing at the foot of her bed, a sour-looking guard is posted. When I ask why, the woman says she is part of a round-the-clock security detail making sure nobody steals the child. Had temperatures outside not been nudging 112F, and the atmosphere on the ward not been equally oppressive, I might have found the energy to argue how ludicrously unlikely that seemed. Instead, I simply ask if the little girl has been given a name. “No,” the guard snaps, folding her stout arms. “She’s just called No-Name baby.”

It is hard to say if this little scrap of life is lucky or not. If she survives, she will be returned to the nuns. From there, they hope she will be adopted by a local family, though this too seems unlikely.

“Most families would rather eliminate their girl child in the womb or neglect her once she is born, slowly starve her, poison her or ignore it when she gets sick, than abandon a child, as that is considered dishonourable,” says Kumari, noting that female infanticide has existed for thousands of years in India.

For this reason, she and many others dismissed as a publicity stunt a declaration made earlier this year by India’s minister for women and child development, Renuka Chowdhury, that every town should have a cradle such as that outside the Chandigarh orphanage, where parents can abandon baby girls to the state rather than abort them. But if there is little substance to this proposal, what is the Indian government doing to tackle this crisis?

A poster hanging outside the office of India’s health minister, Dr Anbumani Ramadoss, reads: “A daughter brings complete happiness in your life.” It is part of the government’s campaign to crack down on female foeticide and, as the minister later tells me, he is the father of three daughters. But it is late in the evening when I am finally ushered into his office, and Dr Ramadoss looks intensely weary, rather than happy.

“I am responsible for the health concerns of a sixth of the world’s population. It is a big job,” he says. “India is not in denial about this issue. We are really ashamed of what is happening here. Child sex ratios are something we are very, very concerned about. My prime minister is very concerned. So is parliament. I love my daughters very much and this issue agitates me greatly.”

For the next hour he outlines a series of government initiatives, including requiring a woman to register her pregnancy, not just the birth of a child; funding MPs to raise social awareness of the problem; enlisting the help of religious leaders of all denominations in preaching against such practices; and increasing penalties for both doctors and families engaging in sex selection to between two and five years’ imprisonment and impressing on the judiciary the need to prosecute such cases. There are also moves to recruit more police officers onto local committees responsible for enforcing the PNDT Act. Currently they are often headed by doctors, meaning, in effect, that doctors are policing other doctors engaged in illegal practice.

When I ask if India is learning any lessons from China, Ramadoss bridles. “India is not China,” he says, pointing out that the problems of changing social attitudes and enforcing laws in the world’s largest democracy are far more complex than bringing about change in a one-party Communist state. Yet when I meet Deepa Jain Singh, of the Ministry of Women and Child Development, I learn that India, similar to China, will shortly be piloting a project to make cash payments to couples when they register the birth of a daughter and later when they immunise her and enrol her in school. In recent months, laws governing the adoption, both by Indian and foreign families, of abandoned children, have been relaxed. A campaign stressing that religious ceremonies, such as last rites traditionally performed only by sons in the Hindu faith, can be carried out by daughters too has also been launched.

“There is no magic wand to solve all these problems,” says Jain Singh. “Nothing can be done by diktat. No one can legislate for decisions made behind the doors of a bedroom.”

Others strongly disagree. Among them, Sabu George, one of India’s leading activists against female foeticide. He believes the key is to crack down on the sale of ultrasound machines to unlicensed practitioners so that couples can’t seek illegal sex-selection tests. While there are around 30,000 registered ultrasound clinics in India, it is estimated there could be two to three times as many in operation, using machines ranging from sophisticated £50,000 models to refurbished and portable ones costing less than £5,000.

In April this year, a criminal case was brought against General Electric – by far the largest seller of ultrasound machines in India – for supplying machines to unregistered clinics carrying out sex-selection tests. But the company says it is not to blame for unethical practice, likening such accusations to car manufacturers being blamed for reckless drivers. But George, who condemns multinationals for also helping doctors purchase ultrasound machines with bank loans, labels the machines “weapons of mass destruction”. “The Nazis’ extermination programme was only halted because of international intervention. I believe it is high time there was international outrage at what is going on here now,” he says.

While in the past families would allow the birth of at least one girl, now they are choosing to terminate even that pregnancy, says George, who also talks of British Asian families going to India for sex-selection tests and terminations after being effectively barred from NHS treatment after repeated abortions. Yet many have been reluctant to speak out on the issue, he says, for fear of being labelled anti-abortion.

“The time for academic debate on who is to blame for this has long gone. Time is not running out. It has run out. The situation is dire. We need immediate firefighting teams to put a stop to this catastrophe,” says Puneet Bedi, stressing however that the financial and political clout of the corrupt clique of doctors engaged in illegal practice should not be underestimated. One measure of such clout is the bribe of £16m allegedly offered by a group of doctors to stop an undercover documentary on female foeticide being aired on Indian television last summer.

“We are not talking about a few black sheep here. If close to 1m girls are being aborted every year, that means between 2 and 3m illegal acts are being performed, if you consider that only one in two sex-selection tests will reveal a baby is female, and that test leads to an abortion.”

Bedi believes the most effective way of exposing corrupt medical practitioners is to meticulously comply with the PNDT Act, which mandates that the records of anyone under suspicion be carefully audited, comparing tamper-proof birth-record data with other medical forms every doctor is obliged to register. As Bedi sits hunched over his laptop computer drawing up one computerised public record after another, to illustrate this, his tenacity reminds me of the American legal clerk Erin Brockovich and her hunt for the devil in the detail in bringing down corrupt giants in the US corporate world.

When I ask Bedi where his zeal comes from, his reply sends a shiver down the spine. “As a fourth-year medical student, I was on a hospital ward and witnessed a cat dragging a female foetus along the floor,” he says, lowering his voice as his two daughters sit nearby. “What appalled me was that nobody was appalled. That scene has stayed with me for 20 years.”

The scene from this investigation that stays with me is that of standing in the crushing heat of an operating room at the Bawa Nursing Home in Fatehgarh Sahib, as Dr Ravinder Kaur lays out on a red plastic operating table the instruments with which she carries out abortions. As she carefully lines them up, she describes how the resulting “products” are then disposed of; collected by a contractor every few days along with other bio-waste, to be incinerated.

All abortions she carries out, Dr Kaur stresses, fall within the medical guidelines of the MTP Act, which allows pregnancies to be terminated under a number of conditions, including failure of contraception. The nursing home is run by her husband, Dr Navindar Singh Bawa, who, for the past three years has been chairman of the local committee responsible for enforcing the PNDT Act. One room tucked behind his garage is full of posters and pamphlets he is proud to show he has designed denouncing female foeticide.

Yet when Dr Bawa starts to discuss the reasons for it happening, the fact that this district has the lowest ratio of girls to boys anywhere in India seems less surprising. Initially he says the ratio is probably not as low as it seems, since parents immediately register the birth of a son but sometimes fail to register the birth of a daughter “because they are unsure she will survive”. This undoubtedly happens, though what it says about the care of infant girls is another matter. Then Bawa changes tack and says the low ratio is happening naturally.

“Naturewise,” he says, it is happening “just by chance, not related to female foeticide”. This may be due, he says, to “diet” or “behaviour and genetics” or “climate change”.

Sitting later in a nearby Hindu temple to discuss the view of religious leaders on the dearth of baby girls in this district, one worshipper suddenly starts talking about Bawa, saying he was the first doctor in the area to have an ultrasound machine. “He did thousands, laakhs, [hundreds of thousands] of tests,” the man says. “Every girl used to go there and he’d say, ‘Come on, lie down, we’ll take a picture.’ Now he is on the other side.” The atmosphere in the room stiffens. Even though his comment may have been no more than a rumour, out of the corner of my eye I see the priest signalling the worshipper to stop talking. “He didn’t mean to harm anybody, of course,” the man says quickly, adding that the “tests” must mostly have been for knee problems.

As we drive away from the temple, I pull out one of the postcards Bawa had designed and thrust into my hand. On the front is a graphic drawing of a foetus in the womb pierced by a knife and dripping blood under the words “Female Foeticide – A Crime”. Turning the card over, I read the words printed there and shudder. Addressed as an “Appeal to dear medical professionals”, it reads, “Whoever has been negligent, but later becomes vigilant… Whoever has done harmful actions, but later covers them with good, is like the moon which, freed from the clouds, lights up the world.”

Some names have been changed to protect identities