September 14, 2008

September 14, 2008

Investigation

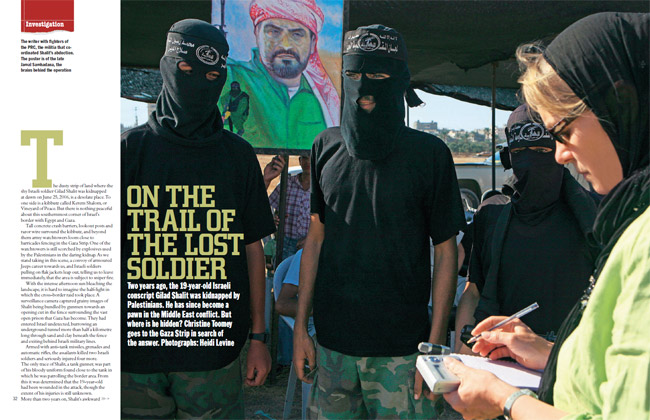

Two years ago, the 19-year-old Israeli conscript Gilad Shalit was kidnapped by Palestinians. He has since become a pawn in the Middle East conflict. But where is he hidden? Christine Toomey goes to the Gaza Strip in search of the answer. Photographs: Heidi Levine

The dusty strip of land where the shy Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit was kidnapped at dawn on June 25, 2006, is a desolate place. To one side is a kibbutz called Kerem Shalom, or Vineyard of Peace. But there is nothing peaceful about this southernmost corner of Israel’s border with Egypt and Gaza.

Tall concrete crash barriers, lookout posts and razor wire surround the kibbutz, and beyond them army watchtowers loom close to barricades fencing in the Gaza Strip. One of the watchtowers is still scorched by explosives used by the Palestinians in the daring kidnap. As we stand taking in this scene, a convoy of armoured Jeeps career towards us, and Israeli soldiers pulling on flak jackets leap out, telling us to leave immediately, that the area is subject to sniper fire.

With the intense afternoon sun bleaching the landscape, it is hard to imagine the half-light in which the cross-border raid took place. A surveillance camera captured grainy images of Shalit being bundled by gunmen towards an opening cut in the fence surrounding the vast open prison that Gaza has become. They had entered Israel undetected, burrowing an underground tunnel more than half a kilometre long through sand and clay beneath the fence and exiting behind Israeli military lines.

Armed with anti-tank missiles, grenades and automatic rifles, the assailants killed two Israeli soldiers and seriously injured four more.

The only trace of Shalit, a tank gunner, was part of his bloody uniform found close to the tank in which he was patrolling the border area. From this it was determined that the 19-year-old had been wounded in the attack, though the extent of his injuries is still unknown.

More than two years on, Shalit’s awkward smile continues to appear regularly in the pages of the Israeli press. His kidnap sparked a new chapter of war in the never-ending Middle East conflict. And his continuing captivity is seared into the consciousness of both sides: the Israelis, who seek his release, and the Palestinians, who see him as a bargaining chip to secure freedom for hundreds of Palestinians in Israeli jails, many of them women and children. The fate of the young conscript, and the possibility of a prisoner exchange to free him, has been the focus of intense, if intermittent, diplomacy. While Egypt has been acting as mediator, France and the EU are making demands for more progress (the Shalits hold dual French/Israeli nationality).

But apart from the release of three brief letters, undoubtedly dictated by his captors, and a stilted audio tape in which Shalit says he needs a prolonged stay in hospital, little is known about him. Some question whether he is still alive since the bodies of Ehud Goldwasser and Eldad Regev, two Israeli soldiers captured by Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia within weeks of Shalit’s kidnapping, were returned recently in exchange for five Hezbollah militants, including a notorious triple murderer.

The continuing uncertainty is damaging the morale of young conscripts like Shalit in a small country that relies for its security on every teenager signing up for national service. In an effort to bolster the spirits of new recruits who wanted to know what was being done to secure his release, Israel’s chief of staff, Lt Gen Gabi Ashkenazi, confidently stated on August 4: “We are making every effort to make sure Gilad Shalit returns home as soon as possible. We know Gilad is alive; we know where he is held and by whom.”

I am sitting in the airy living room of Shalit’s home in Israel’s northern hills bordering Lebanon when his father, Noam, receives a phone call about what Ashkenazi has just said. A glower of frustration clouds the engineer’s face. “I don’t think it’s something serious, nothing new,” he says as he hangs up the phone. Towards the end of our meeting, however, he confesses: “The army is not keeping us informed about what is going on. The person handling all negotiations is a former secret-service officer who doesn’t believe he has to give us any information.” When I tell him I am leaving for Gaza the next day in search of clues to the fate of his son, he tells me not to go: “It’s too dangerous.” Shalit’s mother remains a silent presence in the house as we speak.

To travel into the Gaza Strip is to enter into a heart of darkness in the Middle East. The pain and hatred of those I will meet there does little to inspire hope of a happy outcome to the hostage situation. The raw power-mongering of Palestinian politicians and the militant factions I encounter is matched by the cold calculations of Israel’s leaders, who have worked out the exact price they are prepared to pay to secure Shalit’s release. In the face of this cynical standoff, Shalit’s family is left in agonising limbo.

Passing through the Erez checkpoint from Israel into Gaza is to move from relative prosperity and order to dire poverty and chaos. The first sight that greets you is the twisted metal and rubble of what was once a bustling industrial estate, razed to the ground by the Israeli military in one of many bombardments of the area since Shalit was kidnapped. More than 1,000 Gazans have been killed by Israeli security forces since his abduction.

Nearly every building on the northern outskirts of Gaza City is pockmarked with bullet holes or scorched by Israeli shellfire. But pressing deeper into the city, traces of a different, internal conflict emerge.

After Ashkenazi raised hopes that Shalit might be freed, the government swiftly rowed backwards, stating that all the chief of staff meant was that Shalit was being held in Gaza by Hamas. To say that Hamas controls Shalit’s fate is to state the obvious, as it now exercises almost absolute power in Gaza. A year ago Hamas staged a virtual coup there, seizing power from its rival, Fatah, with whom it had agreed to share power after winning a parliamentary majority in 2006. But even this one fact is far from simple.

In the days after Shalit was seized, three different armed factions claimed they had been jointly involved in the kidnapping: the al-Qassam Brigades (the military wing of Hamas), the Popular Resistance Committees (which include members of Hamas, Fatah and Islamic Jihad) and a previously unknown group calling itself the Army of Islam. Loosely linked to Al-Qaeda, the Army of Islam, which gained notoriety for the kidnapping of the BBC reporter Alan Johnston, is regarded by many as the private army of the infamous Doghmush clan, who are sometimes referred to as “the Sopranos of Gaza City” for their involvement in organised crime.

One of my first meetings in Gaza is with Mahmoud Zahar, the militant hardliner and co-founder of Hamas. Zahar is the real power behind the Hamas prime minister, Ismail Haniyeh, and the one person who might be expected to deliver answers about Shalit. But the stooped 63-year-old surgeon is the first of many brick walls I come up against in Gaza. Like nearly all of those I speak to, he will not confirm where we are to meet until minutes before the meeting. He fears being targeted not only by Israeli missiles – which have homed in on the precise whereabouts of many Palestinian leaders, killing them in lightning air strikes – but also by gunmen from Fatah and by the Doghmush clan.

Zahar’s heavily guarded base is in the heart of Doghmush territory, in the Sabra neighbourhood to the south of Gaza City. At first we are due to meet him as he finishes midday prayers at a mosque there. Gunmen standing guard outside the mosque say he is too afraid of sniper fire to worship there – though he later denies this. A call then comes telling us to go to his home, where we are instructed to sit on plastic chairs outside the front door to await his arrival. It seems an unlikely place to meet if he is worried about being targeted: the entrance is overlooked by tall, apparently empty, bullet-scarred buildings with broken windows – perfect sniper perches.

But when he eventually arrives, Zahar doesn’t linger long. “Nobody from the political or military wing of Hamas knows where Shalit is,” he says, disingenuously, sitting by my side in a starched safari suit. “Only the small group who kidnapped him know. They are very secretive.”

He says he has no idea of the conditions in which Shalit is being held, only that they must be better than those of the more than 1,000 Palestinian prisoners whose release Hamas is demanding for his safe return. Before we are ushered out, Zahar allows us into the basement of his spacious three-storey house, where he has built a shrine to two sons killed in Israeli air strikes in the past five years.

Before meeting others in the armed factions responsible for Shalit’s kidnapping, I try talking to more moderate Hamas politicians.

Dr Ahmed Yousef, one of Hamas’s top political advisers, is a suave academic much more comfortable than Zahar with media contact.

As we sit talking in his sweltering office, he boasts of his role as a consultant to the American thriller-writer Tom Clancy on subjects related to terrorism. But on the subject of Shalit, Yousef, too, is tight-lipped.

“The Israelis have Gaza under such a high level of surveillance, they can smell what we’re eating,” he says, “so nobody will talk about Shalit. It puts them in great danger if they do.”

Then he adds: “I don’t recommend you go around asking too many questions about Shalit. People get suspicious.” I was warned before coming to Gaza that I might be regarded as a spy.

“You have to understand the people in Gaza,” Yousef continues. “They can’t see why the world is so concerned about one Israeli soldier captured by freedom fighters resisting occupation when nobody takes any notice of the thousands of Palestinian prisoners held illegally.”

Yousef’s argument ignores the fact that hostage-taking is a war crime. But it underlines Palestinians’ grievance about prisoners held in Israeli jails. There are some 9,000 Palestinians in prison in Israel, many held without charge or trial on “administrative detention orders” that are often renewed for months or years. After Shalit’s capture, dozens of democratically elected Hamas politicians, including a third of the Palestinian cabinet, were arrested; 45 are still in detention.

While Zahar and Yousef are reluctant to discuss Shalit, members of the Doghmush clan are happy to brag about how well he is being treated. I meet them in a garage of one of the many buildings the clan owns in the Sabra district. Abu Khatab Doghmush, a 51-year-old clan elder, is sitting with family on a sofa pushed against a wall. As I take a seat with my interpreter, I notice a bullet on the floor in front of me.

Abu Khatab insists that the Army of Islam is not holding Shalit. “The only faction that controls his life now is the Qassam Brigades,” he says, his heavy gold watch flapping against his wrist. “But I can tell you that Shalit is living in a paradise. Our religion of Islam demands that we look after prisoners even more than we do our own people.” He rejects speculation that Shalit is locked deep in an underground cell booby-trapped with explosives: “He’s not being kept in a closed room all the time – this would not be healthy. He can go out and take fresh air.”

Abu Khatab then makes an extraordinary claim: “Every year a party is held to celebrate his birthday. Yes, there is a cake and candles, music, everything.” Shalit, born on August 28, 1986, has now spent three birthdays in captivity.

The claim that Shalit is being well treated is repeated by everyone I meet. His plea that he needs hospitalisation is dismissed by Abu Khatab. “No, it is I who require hospitalisation,” he says, kicking off his plastic sandal to reveal a foot eaten away by gangrene. He then lifts his shirt to show a festering wound from recent stomach surgery. “We have no medicines in our hospitals. Look at how we are forced to live. We blame the western media for siding with Israel,” he says, growing increasingly agitated. It is time to leave.

That night, as we drive south towards Rafah, where it is thought most likely that Shalit is being held, a squad of heavily camouflaged al-Qassam soldiers appear out of nowhere and march along the road towards us, chanting praise to Allah. As Heidi, the photographer, leaps out to start taking pictures, our driver tells me not to move from the car and goes after her. The soldiers quickly disappear into provisional barracks nearby.

Over the days that follow, repeated attempts to talk to the al-Qassam Brigades are rejected. Again and again I am referred back to Hamas political leaders such as Zahar as the only ones able to speak about Shalit. With Zahar and others claiming only al-Qassam knows anything, the circle of professed ignorance and denial is closed.

In my search for clues to what happened to Shalit after he was smuggled into Gaza, I then seek out the families of the two Palestinian gunmen killed in the operation.

Ahlam Farwana is the mother of Mohammed Farwana, a 21-year-old university student recruited to take part in the attack by the Army of Islam. She sits on a plastic chair sunk in the sand outside her daughter’s house close to the sea in the village of Qarrash. When I ask what happened to her son, she shakes her head and cries. “The first I heard of what he was involved in was when people started arriving at my house, early on the morning he died, asking if I had heard the news,” she says. “I was in shock. I had absolutely no idea. Even my brothers said, ‘Is it really your son who has done this – the calm one, the good one?’ Nobody could believe it.

“The day before the operation he was looking after an injured bird in his bedroom. He was so gentle. When men from the Army of Islam came to tell me my son was a martyr, I refused to meet them. I was very angry they had wasted my son’s life. I told them never to return, and they didn’t.”

But as we sit talking, I am unaware that behind us, on one of the balconies of the house, a man is listening to us closely. The more questions I ask, the more uneasy he apparently becomes, until he picks up his mobile and starts making calls. “We should leave now,” our driver whispers urgently. As we drive away, he mutters that the man’s Taliban-style clothing, long hair and beard mark him out as a member of the Army of Islam. When I hear that, little of what Ahlam Farwana had to say seems of much relevance.

Pressing on further south to Rafah, I arrange to meet the spokesman for the Popular Resistance Committees, or PRC, which co-ordinated Shalit’s kidnap. Again we are not told of the meeting place until minutes before it is confirmed: a screened-off section of a restaurant, the owner of which is deaf and dumb.

When Abu Mujahed arrives, I am taken aback. We have spent time watching young PRC recruits training – all wear black balaclavas and carry AK-47s. But 24-year-old Abu Mujahed wears a beige suit and brown shirt, a look that would not be out of place in a cheesy video on an Arabic music channel. He has come straight from his brother’s wedding, he says, before explaining in clear English (he is studying multimedia technology at university) precisely how a prisoner exchange should work.

“After the Israelis free the first 100 Palestinian prisoners, Shalit would be moved to Egypt. Once he’s in Egypt, the Israelis would have to free 1,000 more of our brothers and sisters before he is released. We were very close to agreeing a deal a year ago, then the Israelis stopped negotiations. We were amazed that they were prepared to go back to zero. It is the Israelis who are putting obstacles in the way of an agreement.

“If we do not see some results soon, we will be forced to close the file,” he concludes ominously.

When I ask how much he knows about Shalit’s whereabouts and the conditions he is kept in, Abu Mujahed repeats the mantra that he is being treated well, “according to our religion”. Only a small group know where Shalit is held, he claims, and they communicate by means of dead letter drops, mobile phones being too easy to track.

Our next meeting in Rafah – with the family of Hamed Rantisi, the second gunman killed in the kidnapping – sends a shiver down the spine, revealing the depth of hatred felt by those Palestinians who want to see Israel wiped from the map. Like 80% of Gaza, the Rantisis live below the poverty line: when Mariam, Hamed’s mother, opens the fridge, it contains nothing. Mariam, her husband, their five surviving sons and their families exist on handouts of just 1,500 shekels (about £230) a month paid to the families of those “martyred” (killed) or injured in clashes with Israelis.

“I don’t know or care where Shalit is,” Mariam snarls. “All I know is that he is alive and my son is dead, and they won’t even give me his body. Hamas made a mistake allowing messages to be passed from Shalit to his family. They should have made them conditional on my son’s body being returned to me. If I had my way, I would kill Shalit. We are a family of fighters. I hope all my sons become martyrs to liberate Palestine.”

After we leave the Rantisi family’s squalid home, another PRC loyalist, Issa, agrees to take us to the site of Shalit’s abduction, on the other side of the Israel-Gaza border.

Issa knows so many details of the kidnapping that I ask if he was involved. He denies it, but says the operation took six months to plan and was masterminded by the PRC commander Jamal Abu Samhadana, who was killed in an Israeli air strike two weeks before Shalit was seized.

There has been much criticism of Israeli intelligence for failing to stop the attack, despite having picked up information several days earlier that an operation in the area was imminent. Israeli ignorance of where the soldier was taken after the kidnap can be judged by Palestinian claims that collaborators were caught sifting through the household rubbish of doctors in the Rafah area who might have treated Shalit for his wounds and discarded bloody dressings.

None of those I meet in Gaza or later in Israel give any indication that Israeli intelligence officials know where Shalit is being held now – not surprising, since Gaza, a narrow strip of land just 25 miles long, with a population of 1.4m squeezed into a maze of towns and refugee camps, is one of the most densely populated areas in the world. And even if his whereabouts were known, it is widely accepted that any military exercise to free Shalit would put his life in too much danger.

Israel pulled its settlers out of Gaza in 2005, but it still controls who goes in and out of the territory. Since Rafah airport was destroyed by Israeli bombardment, the only way Palestinians can get out of Gaza is via a series of checkpoints controlled by Israel, or one controlled by Egypt. But the checkpoints are almost constantly closed in the face of continuing Palestinian rocket attacks on nearby Israeli towns; they remained closed even during a ceasefire this summer. People cannot leave Gaza to work, and desperately needed goods cannot enter.

To circumvent these restrictions, a burgeoning network of tunnels has been dug beneath Gaza’s border with Egypt. Once clandestine, they now mushroom openly on the outskirts of Rafah, their entrances surrounded by plastic sheeting like giant beach windbreaks. Shalit may already have been smuggled out of Gaza into Egypt along one of these tunnels.

) ) ) ) )

The greatest fear for Shalit is that he will turn into another Ron Arad. Arad was a lieutenant-colonel in the Israeli air force who, more than 20 years ago, parachuted out of his damaged fighter jet on a bombing mission over Lebanon and was captured by the Lebanese Shi’ite Amal militia. When two years of negotiations for his release as part of a prisoner swap failed, and his usefulness to his captors as a bargaining tool dwindled, there were reports that he was “sold” to Iran, but his true fate has never been established.

As recently as two months ago, images of Arad saturated the Israeli media again when Hezbollah handed over two photographs of him in captivity and fragments of a diary he wrote, along with the bodies of Goldwasser and Regev. One photo showed Arad in pyjamas, bearded, hollow-eyed and clearly injured. It haunted the Israeli psyche and reinforced the feeling that politicians had not done enough to bring the airman home.

In a country founded on self-preservation and the principle that “never again” will its people be held captive, failure to deliver one of its sons or daughters from the hands of the enemy is among the gravest political sins. Though never publicly acknowledged, a directive called the “Hannibal procedure” is thought to operate still within the Israeli military. It rules that soldiers may subject kidnappers attempting to abduct one of their own to the fire power needed to kill them, even if it endangers the life of the soldier in question. “Better a dead Israeli soldier than a captured one” is the thinking behind the secret order, the logic being that the Israeli public copes better with its soldiers dying than being held hostage.

The prospect of Shalit being passed from the hands of Hamas militants – over whom their political masters exert control – to more ruthless and unpredictable extremists with unclear aims is a scenario that frightens his family. As long as Shalit’s current captors see him as a precious bargaining chip – as part of a prisoner exchange and also as a deterrent to Israel’s reinvasion of Gaza – his safety seems assured.

The danger lies in negotiations between Israel and Hamas breaking down. To find out how near this is to happening, I talk to a retired intelligence officer close to the Israeli negotiating team. We meet in a cafe in a small town north of Tel Aviv.

The chilling clarity of the Israeli position only emerges at the end of a lengthy conversation. “We have named our price – 450 prisoners in exchange for Shalit. If they don’t want to pay it, so be it,” says the former intelligence officer, drawing the interview to a close.

For the previous hour he has spoken about the difficulties of dealing with Hamas – condemned internationally as a terrorist organisation – and how hard it is for the Israeli public to accept the release of convicted murderers as part of any prisoner exchange, as is being demanded.

But less than two weeks after we meet, the political games the country’s leaders are playing behind the scenes – and the way these make Shalit’s position ever more precarious – are exposed. With the Israeli prime minister, Ehud Olmert, embroiled in corruption scandals and close to resigning, the cabinet desperately seeks to regain high ground by announcing that 199 Palestinian prisoners will be released imminently. The move is meant as a goodwill gesture to bolster the embattled Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas, based on the West Bank, and to breathe new life into the peace process. It is also meant to send a message that diplomacy, not violence, is the way to win concessions.

Since Hamas seized control of the Gaza Strip last year, the moderate Abbas, Yasser Arafat’s heir as leader of Fatah, has been increasingly sidelined. The release of the prisoners, including two of the longest-serving convicted murderers in Israeli jails, was intended to boost Abbas and Fatah and to deepen Palestinian divisions by pulling the rug out from under Hamas. Most of those freed were members of Fatah; none were Hamas supporters, none from Gaza.

Hamas reacted instantly by threatening Shalit. “If the stubbornness continues,” warned Abu Obeida of the al-Qassam Brigades, “the enemy should consider Gilad Shalit as Ron Arad No 2.”

) ) ) ) )

Noam Shalit is not a man to show his feelings. He holds his emotions coiled tight and, after two years of family anguish, always appears ready to spring into action at the slightest indication that he can influence negotiations to secure his son’s release. During my journey through Gaza,

I discover that behind the scenes he has tried to establish direct contact with those connected to the kidnapping. Several people I speak to say he has called them. Even as Olmert’s reign draws to a close, Noam continues to hold meetings with the prime minister, with his possible successors and with international diplomats. But Noam’s impotence in exerting influence on the key players seems to be reflected in his faraway stare.

The second time we meet, in a Tel Aviv hotel, I struggle to decide whether to tell him about the yearly birthday party, with cake and candles and music. Three weeks later, his son will spend his 22nd birthday in captivity. On his 20th birthday his family released 2,000 balloons at the site of his kidnapping, with messages attached calling for his release. This year there are no such plans. Thinking this claim that his son is being well treated might be a crumb of comfort, I do mention the party. But as Noam Shalit winces, I realise I have made a cruel mistake.

“Time is against Gilad,” he says. “They say the state is doing its utmost to bring him back, but in terms of results – there are no results.

“Gilad is not much of a talker. He’s very shy and introverted. His passion is following football and basketball on TV. He wanted to serve in a tank unit like his cousin, though he could have joined a non-combat unit because his health profile is borderline.” (Gilad has problems with his eyesight and his back.)

Asked how he thinks his son is coping with captivity, Noam replies: “We hope he is strong. But he was very young when he was kidnapped. How can we know? How can anyone know how they would react in such a situation?”.

Next Sunday, a rally will be held in central London followed by an event at the Lyric Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue, to highlight the plight of hostages worldwide, especially Gilad Shalit (www.walkingforgilad.co.uk )

9,000 in prison in Israel

Imad Taqatqa, 15, is one of an estimated 9,000 Palestinians – including about 70 women and more than 300 children – being held in Israeli jails. His parents, Rihab and Sami, hope he will be released as part of an exchange for Gilad Shalit. Imad, who is awaiting trial on charges of throwing a Molotov cocktail, was shot in the foot and arrested close to a Jewish settlement near his home outside Hebron, in the occupied West Bank. Of the hundreds of Palestinian children imprisoned in Israel, about half are behind bars for throwing stones.