November 9, 2003

November 9, 2003

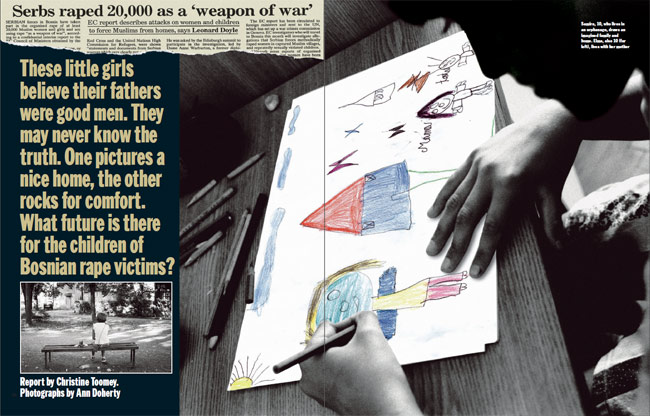

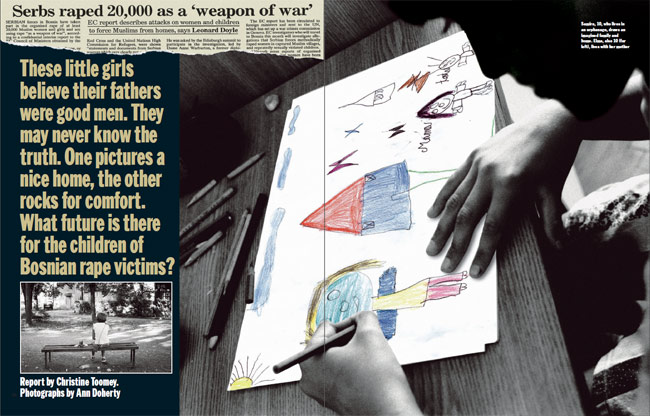

These little girls believe their fathers were good men. They may never know the truth. One pictures a nice home, the other rocks for comfort. What future is there for the children of Bosnian rape victims? Report by Christine Toomey

The moments when Jasmina feels greatest tenderness towards her child are when her daughter whispers: “Close the door, Mama. I want to rock a little.” Alone then with her mother, 10-year-old Elma will sit silently rocking herself for comfort. “She feels as if this is something that no one else should see,” Jasmina explains. “She has rocked herself like this since she was a baby. Maybe it is strange. But it makes me love her more than any mother should probably love their child.”

Such fierce love has not come easily to Jasmina. When her daughter was an infant crying to be fed, she would pretend she did not hear the baby’s distress. “I used to block out the sound and just leave her, walk away… I had to work very hard to love my child.” This sounds like the admission of a reluctant young mother. But Jasmina’s complex relationship with her child has far darker roots.

Elma is one of the many children born as a result of their mothers being subjected to what is now recognised in international law as mass genocidal rape by soldiers, paramilitaries and police – most of them Serbs – during the savage conflict that gripped the Balkans throughout the first half of the 1990s. No record exists of how many such children were born – though the figure is believed to run into thousands – since many women never spoke of what had happened to them during the war, having abandoned their babies immediately after birth.

More than 10 years after the start of the conflict, the number of those subjected to such sexual torture is still unclear. Official estimates range from 12,000 to 50,000. “For those of us who worked with these women, such statistics have little meaning,” says Dr Ante Klobucar of the Sveti Duh Hospital in Zagreb, the Croatian capital where many of those who had been raped secured abortions or gave birth to unwanted babies after fleeing as refugees. “How can the ordeal of a woman held prisoner for months, and raped three or four times a day by a group of six or more soldiers, be measured? Does what she went through count as one rape or several hundred?” questions the doctor, recalling how women, after delivering their babies, begged that the rape-induced pregnancy not be entered in their medical records, so great was their sense of shame and fear of being abandoned by their families.

After years of prevarication over intervening in the conflict that cost more than 200,000 lives, the international outcry at reports of mass atrocities committed against women in Bosnia was one of the key factors responsible for eventually pushing world leaders to take action to end the war. The image of a young Muslim woman who hanged herself from a tree with a piece of torn blanket, in despair at the brutality, remains one of the most haunting of the conflict and has been cited as one of the catalysts prompting President Bill Clinton to eventually change US policy in the region.

But once all political capital had been wrung from the atrocities to which these women were subjected, their suffering was quickly forgotten: their plight no longer constituted a fashionable cause. While those who were left physically disabled by the fighting – such as amputees and paraplegics – receive modest monthly payments, rape victims, who are more psychologically than physically scarred, are entitled to nothing.

Many of these women now live in miserable circumstances, often in “collective centres” little better than refugee camps, after being ostracised by their families or left homeless after being forced to flee homes to which they are still afraid to return. Though a key provision of the Dayton accords – which brought an end to open hostilities in November 1995 – stated that every displaced person had the right to return to their pre-war home, few can contemplate going back to communities where their tormentors still hold positions of power.

In the eastern half of the country known as the Republika Srpska – the vast swathe of territory ceded to the Serbs for the sake of peace – many of those responsible for mass murder, ethnic cleansing and mass rape continue to hold public office and work in the police force. Together with the paramilitary groups that still hold sway in this quasi-closed sector of society, they fight any attempt to extradite war criminals to the Hague.

Over the past three years a steady stream of women and girls – some as young as 12 – have made legal history by testifying at the war-crimes tribunal to the operation of a network of rape camps around the country during the conflict, which has led to war rape being recognised for the first time ever as a “crime against humanity”. But some of those who have either already given evidence before the tribunal or are due to do so are incensed at the way that what happened to them has been used for political and legal ends, while the way they have been stigmatised since is ignored – both within their own country and by the international community.

Yet if the problems these women face have deepened since the fighting stopped, those of the children born as a result of rape are only just beginning. In a society where the issue of war rape is still taboo, they barely receive a mention. Few even acknowledge their existence. While the right to have their identities protected is beyond dispute, hiding their problems and denying they exist will, mental-health experts fear, only add to their burden in the long run.

Jasmina is one of the very few of these women who chose to keep the child she bore after being raped. For years she suffered taunts from those who knew, or suspected, what had happened to her during the war, and who would openly deride her daughter as “that bastard child”. Sometimes, when she took Elma out for a walk, they would shout after her: “There goes that whore – and look, she’s given birth to another whore.”

But the softly spoken 28-year-old has agreed to speak out about her experience from a deeply held conviction that honesty is ultimately in the best interests of her child. Jasmina also considers herself lucky. A few months ago she got married – a step rarely taken by those who have been through such wartime experiences – and recently she has moved away from her home town to a village where her husband’s family have welcomed her and protect her privacy.

“They are good people and he is a good man,” she says. “He knows what happened to me. He was a prisoner too. He understands.”

In other ways Jasmina’s experience is not typical of that suffered by other women during the war. Her ordeal lasted only one night. Her attacker was a Croat soldier rather than a Serb, and he was the only one who tortured her, though he did not act alone. Jasmina, a Muslim, believes a group of Catholic girls she was at school with betrayed her by leading her to her attacker and then leaving her to her fate. Jasmina, who had just finished high school, was unprepared for how quickly the ethnic hatred that was tearing her country apart could infect the group of young people with whom she had grown up.

After she agreed to meet the girlfriends for coffee one afternoon, they led her to the car of her attacker, who abducted her and drove her to a remote hunting lodge. There he bound and tied her, taped her hair to an iron post and subjected her to hours of sexual torture before finally releasing her. Jasmina turns her head away and tears roll down her cheeks as she talks of that night in early 1993. When she realised she had become pregnant, she left her parents’ home with the equivalent of just £2 in her pocket and, despite heavy fighting in the area, managed to make her way to Zenica, 40 miles north of the besieged Bosnian capital of Sarajevo. There she begged doctors to perform an abortion. They refused on the grounds that her pregnancy was too advanced.

Both unable and unwilling to return home – Zenica had by that time become sealed off and she was too afraid to tell her parents what had happened – she was sent to a refuge run by Medica, an organisation founded by a German gynaecologist who was determined to provide medical and psychological help for raped and traumatised women.

“Her pregnancy was very hard,” recalls Marijana Senjak, a psychologist with Medica. “Like other girls and women in her situation, she did not accept that she was pregnant. She somehow dissociated herself mentally from the child she was carrying, and even when the baby was born, wanted very little to do with her.”

But seven days after her daughter’s birth, Senjak and others arranged for a traditional Muslim naming ceremony to be held for the child at the refuge, where hundreds of rape victims had by that time sought treatment.

According to custom, prayers of peace and hope were whispered first in the right and then in the left ear of the infant, who was then passed around the assembled group – many of them rape victims too – as a sign of their acceptance of the child. After the other women accepted Elma, then, very slowly, so did Jasmina.

When, at the end of 1992 and early 1993, it became clear that rape was being used as a systematic means of ethnic cleansing – particularly with Muslim women being impregnated and held long enough to ensure they would give birth to “Chetnik” babies – Bosnia’s leading Muslim clerics issued a fatwa. The decree was meant to dispel the prejudice that held these women as somehow responsible for their own misfortune, and was intended to dissuade families from maintaining honour by rejecting wives and daughters who had been tortured in this way. Rape victims should be regarded as martyrs, the clerics declared, and children born of rape, if their mothers chose to keep them, should be accepted and supported by the women’s families and the rest of the community.

The declaration made little difference. Jasmina was forced to remain in Zenica, then under siege, for the next two years. But when she did return home, although her father took the child to his heart, her mother cursed her for not abandoning Elma after she was born.

“It was only when she saw how determined I was to keep the child that she began to change her mind,” says Jasmina. “Now I realise it was my daughter who helped me back to some sort of normality. Perhaps that is why I love her so much.”

But, Jasmina admits, had her child been born male, she would not have chosen to keep him. “Even now, when my daughter gets angry there is something in the expression on her face that reminds me of the one who did this to me,” says Jasmina, her voice trailing off as she lights another cigarette. “I feel like hitting her in those moments. I have to walk away to calm myself. Imagine what that would be like if I’d had a boy.”

Some had no such choice. Amra Sarac, a lawyer and head of a large social-welfare department in Sarajevo, remembers the first time she was called to the bedside of a woman who had just given birth to a child conceived as a result of rape. “I held her hand for a long time. ‘All right, my darling,’ I told her. ‘We will talk about it. But you will, of course, keep the child…'”.

“I’ll never forget the look in her eyes,” Sarac says. “I was wrong. I saw immediately that the child was the trigger for her trauma, and what I had said had traumatised her further. She did not even want to look at the baby. She left the hospital shortly afterwards. Every time I had a call to attend the maternity ward after that, I knew the cause.”

As she talks, Sarac sifts through a pile of photographs of children born to mothers who had been raped and who were given up for adoption immediately. Some are smiling toddlers, others a little older. Sarac declines to say exactly how many such children were born that she is aware of. But a list of names that accompanies the photographs runs to several typed pages.

“These children became like my own. Their own mothers never set eyes on them. They realised instinctively that if they looked at them or held them, they would not be able to give them up.” Most of the children were adopted by couples in Sarajevo – a brave move, she says, by those who did not know if they would survive the war.

But it was the experience of two sisters referred to her clinic that has particularly haunted Sarac. Both women were suffering from multiple physical injuries and were so traumatised that they could only communicate in short, confused sentences and found it hard to remain in confined spaces. Over the months of therapy that followed, their horrific story slowly emerged.

At first glance, the municipal garage in Hadzici, a small town 30 miles southwest of Sarajevo, appears a bland enough place. Over the past year it has been given a fresh coat of paint and new doors at the top of a ramp that leads to its lower floor. But through a tangle of weeds, an opening to the rear of the building reveals its cavernous interior, and the atmosphere in this place, despite the stifling summer heat, seems to suddenly freeze – a familiar feeling in this country of ghosts. A small sign above the entrance to the garage, reading, “With pain they win the dark, with courage they write the truth”, is all that remains now as a reminder of the atrocities carried out here during the war. It is a tribute to more than 50 Bosnian Muslims, many of them elderly and sick, held here by Serb forces in May 1992. Some in the town say they could hear the screams of those held at this site being tortured at night.

After several weeks, those prisoners who survived were moved to positions elsewhere in Serb-controlled territory and most were never seen again – except for the two sisters, who continued to be held here. How deeply the elder of the two women must have regretted her protective instinct that led them to be kept in this stark, concrete bunker is impossible to imagine. For as fighting intensified around Sarajevo in early April 1992, the elder sister – then a 26-year-old mother of two – growing fearful for the safety of her younger sibling, had left her home one morning and, dodging sniper fire and negotiating military roadblocks surrounding the capital, managed to reach the village near Hadzici where her 19-year-old sister was working. But when the two women tried to return home, they found themselves trapped. The military cordon that was to hold Sarajevo under siege for the next three years had become a stranglehold. Stranded at a roadblock, the sisters were arrested and were eventually taken to the municipal garage, where they remained captive for more than two years.

On one occasion the two women, both Muslim, were herded across the road to a Serb Orthodox church, where they were forcibly baptised, as soldiers stood by jeering and shouting that they were “war loot”. Throughout the period of their captivity, both women were raped repeatedly by Serb soldiers and paramilitaries.

The elder sister was the first to discover she was pregnant. In the depths of a bitter winter she gave birth to a son. The baby remained locked in the same squalid circumstances as the two women. They had little choice but to take care of him. A few months later, the younger sister also realised she was pregnant, but was able to get word to a doctor, who came to perform an abortion. For more than a year after that, the systematic rape of both women continued.

In the damp, dark, concrete garage, with no heating and little food, the baby quickly became sick and developed acute bronchitis – the only reason, Sarac believes, that all three were released. Of all the women Sarac treated, she says the elder sister was the only one who kept her child.”She had no choice. The baby was with her for so long that a bond was formed. By the time she had the chance to give the child up for adoption, she could no longer bring herself to do it.”

In due course the elder sister, together with the small boy, was reunited with her husband and two older children, though the family is now struggling with problems. The fact that they were reunited is exceptional. The majority of raped women who were married and whose husbands survived the conflict could not return to their families. Many left the country as refugees. But for the thousands of women who have remained, the situation is miserable.

“Their lives are terrible. Most are chronically ill,” says Sarac, who describes the failure of European leaders to put a stop to the carnage sooner than they did as the behaviour of an “old whore”. She adds with disgust: “The rest of Europe stood by for so long and allowed this to happen. Now these women and children go on suffering the consequences.”

With the flow of international aid into Bosnia declining, as more recent conflicts demand global attention, the lives of these most neglected victims of war can only get worse. Lack of funding is forcing Medica, for instance, to scale back from next year the counselling and health-support services it has continued to provide since the war. In recent months, the organisation has begun lobbying for a state commission to be set up to deal with the problems these women face, not only with their health and raising children, but also, crucially, with housing. Medica is also planning a campaign to change public attitudes to the country’s rape victims.

Part of the campaign is to lobby the Bosnian government for rape victims to be afforded “civilian war victim” status, currently reserved for those with physical disabilities. Not only would this be an official recognition of what happened to them – a step towards destigmatising their trauma – it would also secure them and their children limited financial support. It could give those women who can still work some priority when applying for certain jobs – a crucial advantage with unemployment running at over 60%.

This will do little, however, for women such as Sahela, 46, now so frail she looks more like a woman in her late sixties. In the picture that she treasures of her handsome teenage son slouched smiling beside her on a sofa, she is totally unrecognisable. A few months after the picture was taken in 1992, Sahela’s 15-year-old son was beheaded in front of her as he begged Serb soldiers not to drag his mother away. After ordering Sahela to bury his body on the spot, the soldiers then raped her in her own home and did so again repeatedly after that in a rape camp, where she and other women were kept tied to beds. Sahela recalls how one young woman she describes as a noted beauty managed to break free from her captors and, crying out for her mother, killed herself by hurling herself through a closed upper-floor window to end the continuing torture.

Sahela is among those who have testified at the Hague, but is bitter about the way she has been ignored since. “They made my story part of history. But I do not want to be treated as history. I want a life,” she says.

She receives the equivalent of £17 a month in compensation for the loss of her son, and scrapes by in a cramped one-room apartment. She wanted to speak out, to get others to take notice, but the strain of doing so saw her being readmitted to hospital for treatment later in the evening of the day we spoke.

Given the unwillingness to discuss or deal with the problems of those women who have been raped, the reluctance to even admit to the problems faced by children born as a result of such crimes is unsurprising. But there are limits to such denial. For no matter how protective women like Jasmina are, or how hard adoptive parents try to shield the truth from children abandoned by their mothers, as they reach adolescence these young people will start asking questions about their backgrounds.

“In the early years, a child may ask very little about his or her father – especially after picking up unspoken messages from those around him that he should never be discussed,” says Zehra Danes, a child psychologist. “But, consciously or unconsciously, many of these children will have felt rejected and have started displaying problems as a direct result of having to fight to be loved.”

Aside from the way in which Elma rocks herself for comfort, Jasmina admits her daughter is a solitary child, preferring to sit for hours alone with headphones on, listening to music. When she started primary school, Jasmina remembers being called in by Elma’s teacher, who wanted to know why the young child always cut any mention of fathers out of stories being told in the class. “I told them they had no right to ask such questions, and told my daughter that if anyone asked her she should say I am both her mother and her father, that her father was killed in the war.” But often, Jasmina says, she would cry when she had to discuss such things with her daughter.

Some people believe that those children given up for adoption might fare better than the small number who have remained with their mothers. It is thought that some women who chose to keep their babies might have clung to them as a kind of emotional armour, and might risk rejecting them later as they gradually associate the child with the assault that led to their conception. Those mothers who chose to keep their babies and subsequently left Bosnia as refugees to live abroad are said by some to be likely to find life easier both for themselves and their children. But Amra Sarac disagrees. “Wherever they go, these women will take their trauma with them. At least those who stayed here are among those who know what happened, even if it is not openly admitted.”

One brave writer, who accompanied several convoys of women and children out of Sarajevo during the war, and who has remained in touch with a group of raped women who gave birth in a safe house she helped establish on the Croatian coast, is sure that none of the women intend to tell the children the truth about their backgrounds. All of them left for third countries after deciding to keep their offspring. “I sat with them until the early hours of the morning as they discussed the stories they would make up to tell the children about who their fathers were. They even started to believe the stories themselves. I believe it is better that way,” she says. “The courage of these women affected me very deeply.”

Whether or not children should know the truth about their fathers, however, is a subject those at Medica have considered carefully. New family laws currently under consideration in Bosnia are expected to bring it in line with many other countries by allowing adopted children, once they come of age, the right to find out what information is known about their biological parents. “Parents form such a fundamental part of a child’s identity – to find out your father is a killer or rapist can be disastrous,” says Marijana Senjak. “If someone is to learn the truth, it is much better that they do so when they are older, once their personality and sense of self is already established.”

Zehra Danes, however, believes it is quite possible that children will find out on their own. “Once a child reaches adolescence, if he knows nothing about his father, he will do everything he can to find out, and if that child lives in Bosnia, there is a huge possibility that he will discover the truth,” she says. “This is much worse than being told.”

It is for this reason that Jasmina is determined to explain to Elma sooner rather than later the true circumstances that led to her birth.”Perhaps when she starts to attend high school, then I’ll tell her what happened,” she says. “I am raising Elma to believe that we should have no secrets. I want her to hear the truth from someone who loves her.” To certain young people, the truth might make very little difference, however. Of all Bosnia’s forgotten children born of rape, these are the most neglected of all.

Samira rushes forward with a lopsided grin, her oversized shoes flapping noisily. She has a warm nature and readily throws her spindly arms around visiting strangers. Like most 10-year-old girls, she giggles a lot. But her attention wanders easily. She often leans her head slightly backwards and stares quietly and seriously into the middle distance, as if she is lost in her own thoughts.

It is impossible to know what Samira is thinking in these moments. The orphanage in Bosnia where she lives classifies her as a child with special needs. She is a slow learner, finds it hard to concentrate and is easily distressed. As the mental and physical state of a mother when pregnant is known to affect the later development of her child, one cannot begin to imagine the ghosts that lie buried deep within this young girl’s psyche.

There are few details on record about the circumstances leading to Samira’s birth. All that is known is that her mother was a 17-year-old girl from a Catholic family in northeastern Bosnia when she was seized by Serb forces in the spring of 1992 and raped. How long she was held before escaping or being released is not clear. But, like many thousands of refugees, she either trudged on foot or was bused in a convoy out of her beleaguered country in the winter of 1992, and transported to Croatia, where Samira was born in a hospital on the Dalmatian coast in January 1993.

Samira’s mother wanted nothing to do with the child, and the infant was quickly transferred into the care of the Catholic charity Caritas, which in turn passed her into the care of a small children’s home run by a Muslim charity in Zagreb.

As part of the post-war policy to repatriate as many refugees as possible, Samira was brought back to Bosnia in 1996 with eight other children and placed in an orphanage. Two of the other children who, like Samira, had been born after their mothers were raped, were quickly placed with families. Samira was not. For the past seven years she has been caught in a legal limbo.

In the absence of any record of what her mother wished to happen to her child, authorisation for her to be adopted would have been needed from the social-services department in the municipality where her mother lived before the war. But that now lies in the Republika Srpska. In order for the Serb authorities to give permission for Samira to be adopted, they would have to accept financial responsibility for the special care she needs; they would also, indirectly, have to acknowledge the circumstances under which she was born. But in the Republika Srpska, all inconvenient historical facts such as genocide and mass rape are vehemently denied.

One social worker, referring to a note that accompanied Samira’s birth certificate, admits there is little likelihood that the child and her mother will ever be reunited, even if her mother could be traced. The note simply states the mother had made it clear that her child was “unwanted”. Even so, Samira has fared rather better than some of the other children, who, like her, were given over into the temporary care of Caritas in Zagreb but who have even been abandoned by their own country.

For 10-year-old Alen, this is the latest in a pathetic saga of rejections. After arriving in Croatia as a refugee in the autumn of 1992, Alen’s mother had apparently sought an abortion. But like many in her predicament, she was told that her pregnancy was too advanced and she would have to carry the child to term. Hospital records show she did not want her baby’s birth registered and that she left for Germany shortly after he was born – without ever setting eyes on her son.

In the frenzy of media attention that accompanied reports of widespread rape during the Bosnian war, many maternity units in the areas to which refugees fled were inundated with calls from couples offering to adopt babies born as a result of this systematic policy of ethnic cleansing. Alen was adopted by a Croatian couple. But as the months went by, his new parents realised he was failing to thrive. Readmitted to hospital with a chest infection, he was diagnosed as suffering from cerebral palsy. On hearing the news, his adoptive parents disowned him.

“He was returned like damaged goods,” says Jelena Brajsa, the director of Caritas in Zagreb, who was asked to take the boy into her care when he was released from hospital. “To my mind, this second rejection was a hundred times worse than the rejection by his mother.”

Alen was then placed in a home for handicapped children run by Caritas. He is one of five children in the home whose mothers gave birth after being raped and whom nobody would subsequently adopt. But not only have these children been rejected by their birth mothers – and, in Alen’s case, once again after that – they have also been rejected, she says, by the country to which most would agree they belong.

Although many, like Samira, were repatriated after the war, some with apparent health problems were left behind. Last year, says Brajsa, the Bosnian authorities finally agreed to exchange a group of disabled young people of Croatian origin for this group of Bosnian children in her care. “Several months ago they arrived with a group of handicapped adults for us to look after,” she says, “yet still they did not take the children.”

After so many rejections, Brajsa says she could hardly bear now for Alen in particular to leave the care of Caritas. “I can’t imagine who would be prepared to adopt these children now, anyway. They are no longer babies and they have so many problems.” One 12-year-old girl, like Alen, is confined to a wheelchair. Another nine-year-old girl has a history of self-harm. One 10-year-old boy, Mirzan, diagnosed as “hyperactive”, like Samira, rushes forward to throw his arms around visitors and constantly hovers close by. He rarely talks or asks questions, however. “He has never asked about his parents,” says one of his carers, “nor wanted to know where he comes from.”

By contrast, Samira is well informed: she knows she was born in Croatia. But beyond that, her imagination has taken hold. Her parents, she says, live in a “neat and clean house” in Zagreb. “I don’t have a telephone number to call them. I wish I did,” she says. “But when I am older, I will try to find out where they live.” Officially, the orphanage is only authorised to offer Samira a home until she is 18. Where she will go after that is unclear. When asked what she would like to do when she is older, Samira is quick to answer. “I want to be a doctor,” she says. “Then I can look after people.” Though she is making progress at school, she will be lucky to find any kind of work. “The best she can hope for is to become a seamstress,” says a social worker at the orphanage. “But how she’ll ever be able to support herself I don’t know.”

While some children in the orphanage have savings accounts set up in their name, to which various charities make occasional donations, Samira does not. Because the Serb-controlled municipality where her mother was born will not accept responsibility for her, she still has no national identity number, necessary, for instance, for a bank account to be opened in her name. Legally, she does not, in effect, exist.

When she is not outdoors playing with the other children at the orphanage, Samira likes to draw. Sitting quietly at a desk in the corner of the bedroom she shares with two other girls, she draws a picture of the house in Zagreb where she imagines her parents live. It is surrounded by birds and butterflies. To one side of the house she draws herself smiling. On the other side she draws her mother and father – “Mama and Tata”.

“I always think about them, especially at night before I go to sleep,” says Samira, colouring furiously. “I wish they would come to see me – just once. One day, I am sure, they will.”

Some names have been changed to protect identities.

**If you would like to make a contribution to Medica or Samira, The Sunday Times has set up an account from which money will be sent to Bosnia once all donations have been received. So please make any cheques and postal orders payable to “Bosnia – Cradle” and send them to:

News International

Treasury Dept

Fleet House, Cygnet Park

Hampton, Peterborough

PE7 8FD

Please indicate on a note with the cheque if you have a particular preference that the money go to Medica or to Samira.

FT

FT